Our bathrooms harbor surprisingly diverse viral ecosystems. A recent study reveals toothbrushes and showerheads teeming with hundreds of previously undiscovered viruses. While this might sound alarming, these viruses primarily target bacteria and pose no threat to humans.

This research, spearheaded by scientists at Northwestern University and published in Frontiers in Microbiomes, expands upon their earlier project, Operation Pottymouth. The initial aim was to investigate unexplored bacterial microbiomes in common household items.

“There’s so much we don’t understand about the world around us, even seemingly familiar objects,” explains lead researcher Erica Hartmann, a microbiologist and associate professor at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering. “We focused on toothbrushes and showerheads because they’re significant sources of microbial exposure, yet their microbial composition remains largely unknown. Our prior studies identified numerous bacteria, which was fascinating in itself. However, the ‘next frontier’ of microbiology lies in bacteriophages (phages). Phages are incredibly abundant, and our understanding of them is limited. So, we began by exploring our immediate surroundings.”

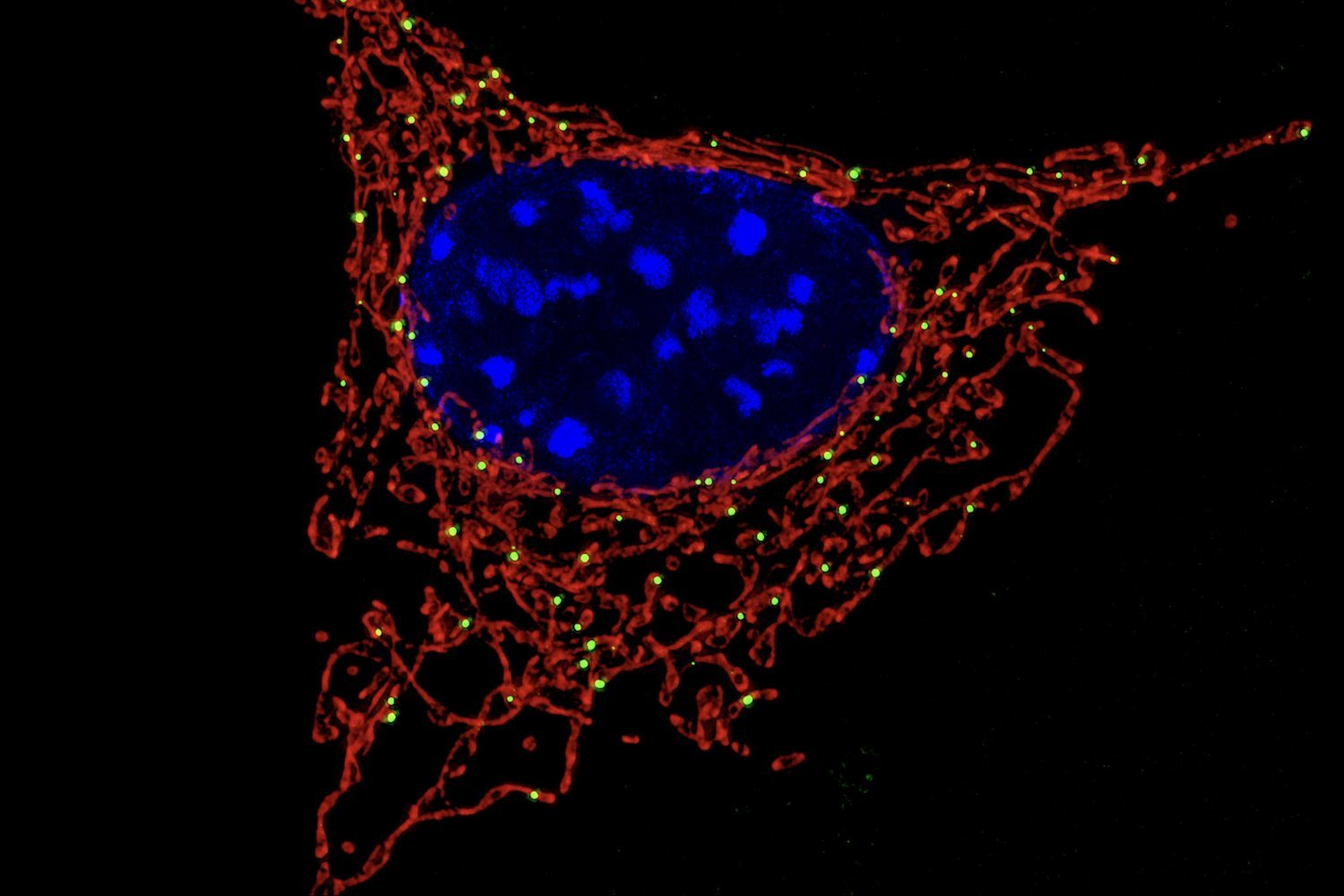

The team analyzed viruses inhabiting the bacteria found on toothbrushes and showerheads. They identified over 600 viruses, the majority being bacteriophages. Although no distinct patterns emerged among the viruses, phages targeting mycobacteria, some of which cause diseases like tuberculosis and leprosy, appeared slightly more prevalent.

“The phages found on toothbrushes and showerheads are unlike anything we’ve seen before,” Hartmann notes. “Not only did we find different phages on toothbrushes versus showerheads, but we also observed unique phage populations on each individual toothbrush and showerhead. This remarkable diversity isn’t specific to these items; it reflects the vast, unexplored world of phages.”

Bacteriophages, true to their name, infect bacteria, not humans. However, their potential as therapeutic agents against antibiotic-resistant bacteria is gaining recognition. Hartmann’s research could potentially uncover medically valuable phages or other microbes within our bathrooms. Even without immediate practical applications, the discovery itself is significant.

“Perhaps the next breakthrough antibiotic will originate from something growing on your toothbrush,” Hartmann suggests. Even if this doesn’t lead to new technologies, documenting phage diversity is crucial for expanding our fundamental understanding of biology.

Recognizing the vast unknown surrounding phages and other microbes, the researchers intend to continue sampling diverse environments, from the mundane to the exotic, to further map their distribution. They are also developing innovative observation methods to study microbial behavior and interactions.

“This will provide a more comprehensive understanding of our daily microbial encounters and potentially lead to new discoveries and inventions that enhance human and environmental health,” Hartmann concludes.