The 2021 discovery of fossilized human footprints at White Sands National Park revolutionized our understanding of early human migration to North America. Initially dated to between 21,000 and 23,000 years old, these tracks suggested humans inhabited the continent thousands of years earlier than previously believed. Now, new research published in Science solidifies these findings, using independent dating methods to confirm the remarkable age of the footprints.

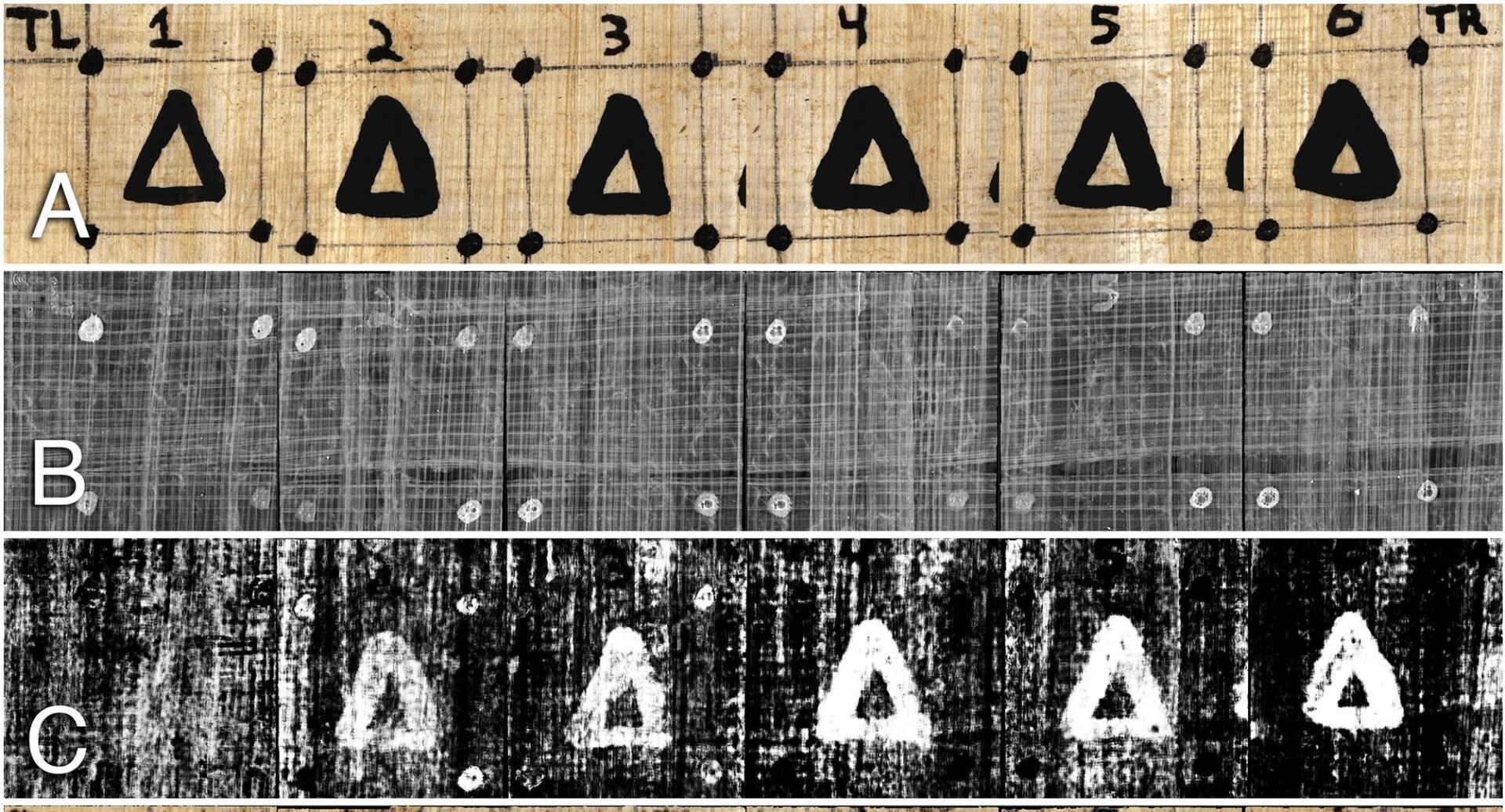

The initial dating relied on radiocarbon analysis of ancient aquatic grass seeds (Ruppia cirrhosa) found within the same sedimentary layers as the footprints. While groundbreaking, this method was potentially susceptible to the “freshwater reservoir effect,” where aquatic plants absorb older carbon from groundwater, leading to inflated age estimates. To address this concern and bolster confidence in the initial findings, researchers employed additional dating techniques.

Footprints, unlike skeletal remains, offer a unique glimpse into the past, revealing details about the individuals who left them. The White Sands footprints, likely belonging to a group including teenagers and children, depict a journey across the landscape, alongside traces of megafauna like proboscideans (mammoths or mastodons) and dire wolves. This snapshot of prehistoric life paints a vivid picture of human presence during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM).

The new research focused on dating pollen and sediments from the site. Pollen, unaffected by the freshwater reservoir effect, provided an independent chronological marker. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating of the sediments offered another perspective, determining when minerals were last exposed to sunlight.

An artist’s illustration of what the region looked like at different points in the last Ice Age.An artist’s rendering showcases the changing landscape of the White Sands region during the last Ice Age, offering a visual context for the human and animal footprints discovered there. Illustration: Karen Carr

An artist’s illustration of what the region looked like at different points in the last Ice Age.An artist’s rendering showcases the changing landscape of the White Sands region during the last Ice Age, offering a visual context for the human and animal footprints discovered there. Illustration: Karen Carr

The results strongly support the original findings. Pollen analysis yielded dates ranging from approximately 23,400 ± 2,500 years to 22,600 ± 2,300 years ago. OSL dating established a minimum age of 21,500 ± 1,900 years for the sediments. This convergence of evidence, from multiple dating methods, firmly places humans in North America during the LGM, challenging the traditional view that human arrival occurred after the ice sheets receded.

The implications of these findings are profound. They suggest human populations navigated and adapted to challenging glacial environments, potentially impacting ecosystems and influencing the course of human history in the Americas. While other sites have suggested even older human presence in North America, the White Sands footprints offer compelling and well-supported evidence of human activity during the LGM.

These footprints represent more than just an age; they provide a tangible connection to the lives of some of the earliest known inhabitants of North America. They offer a unique perspective on human migration, adaptation, and coexistence with now-extinct megafauna. The ongoing research at White Sands promises to further illuminate this crucial period in human history.