The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is leading a research effort to authenticate mysterious uranium cubes found in American laboratories, believed to be remnants of Nazi Germany’s nuclear program. Using nuclear forensics, the team aims to uncover the provenance of these radioactive artifacts, many of which have obscure histories. This investigation, presented at a recent American Chemical Society meeting, sheds light on a little-known chapter of World War II history.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany pursued its own nuclear ambitions. Two separate research groups, one led by Werner Heisenberg and the other by Kurt Diebner, worked on developing nuclear reactors with the ultimate goal of creating an atomic bomb. Following the war, a number of uranium cubes associated with these projects were transported to the United States, where they were dispersed through various channels, ending up in universities, private collections, and research facilities. The challenge now lies in reconstructing their journey.

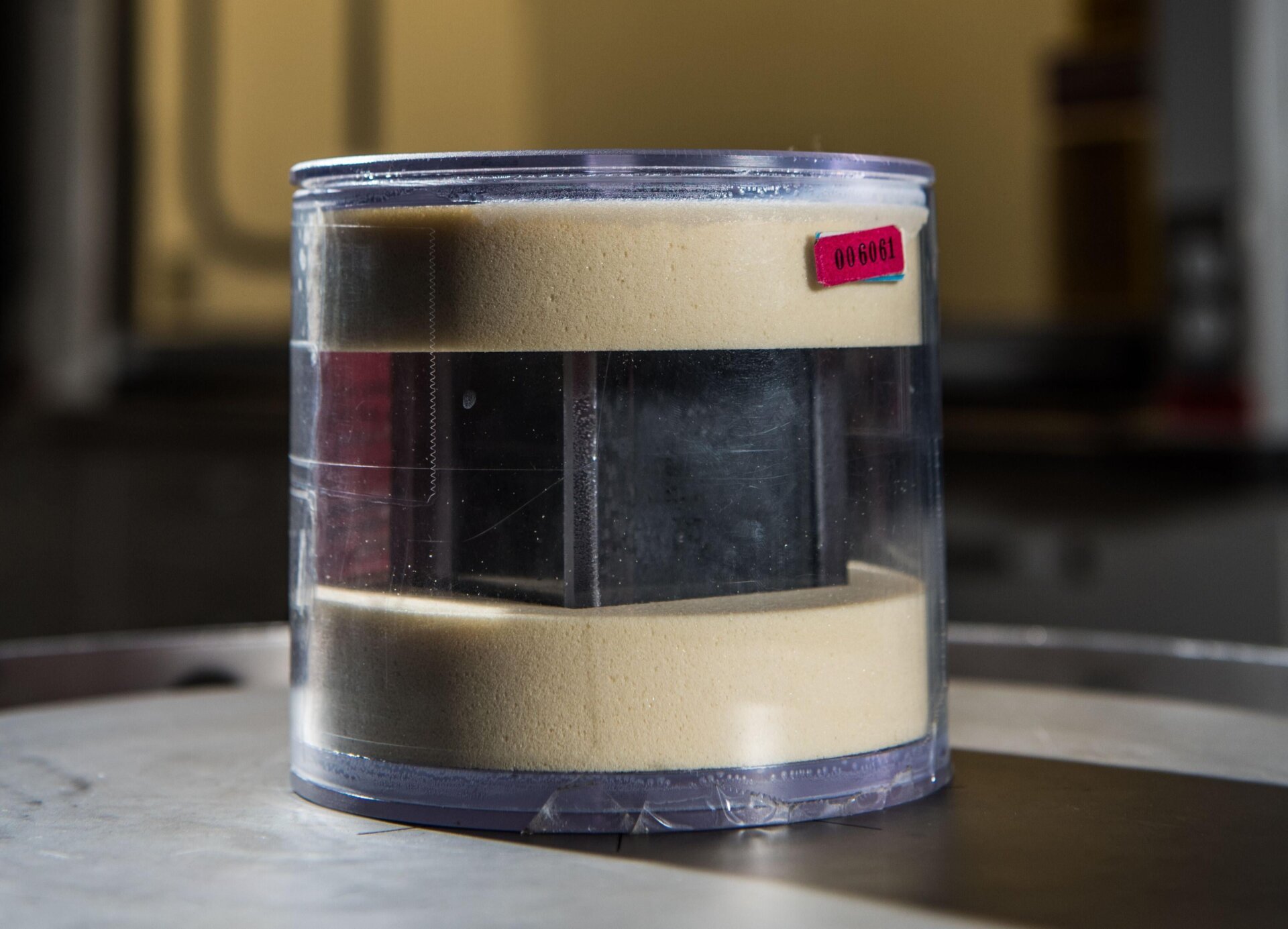

A significant obstacle is the lack of comprehensive documentation for these cubes. Their precise paths and ownership history remain largely unknown. While the researchers estimate that between 1,000 and 1,200 such cubes were part of the Nazi reactors, only about 12 are currently accounted for. The team is focusing on verifying the origin of a specific cube located in Washington State, along with several others, hoping to definitively link them to the German nuclear program.

“Our initial goal is to confirm that these cubes are indeed from the German program,” explains Jon Schwantes, the project’s principal investigator. “Following that, we want to analyze the various cubes and see if we can classify them according to the specific research group that produced them.”

American and British troops disassemble the Nazi’s attempted nuclear reactor in Haigerloch in April 1945.Disassembly of the Nazi nuclear reactor in Haigerloch, April 1945. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

American and British troops disassemble the Nazi’s attempted nuclear reactor in Haigerloch in April 1945.Disassembly of the Nazi nuclear reactor in Haigerloch, April 1945. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

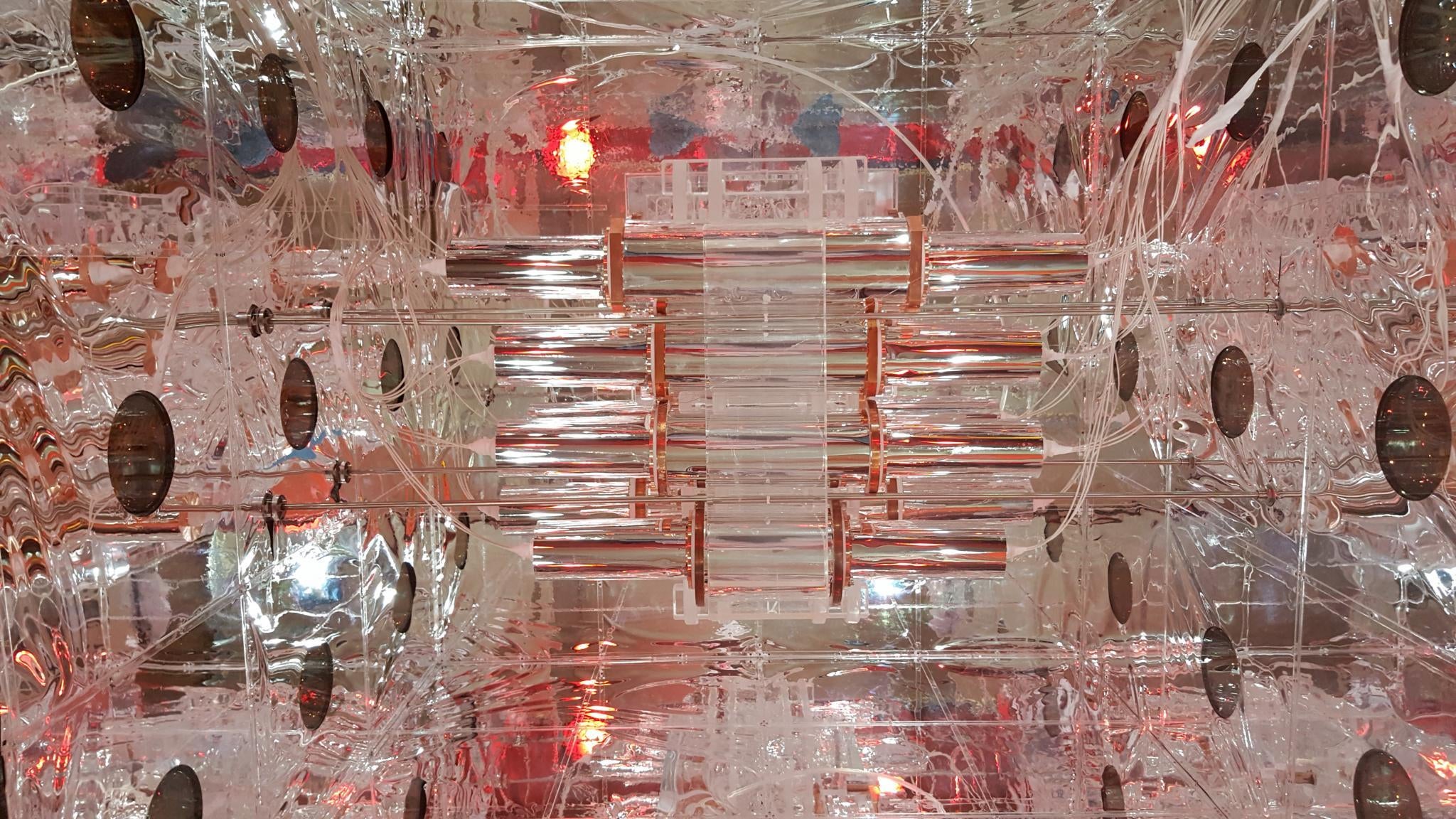

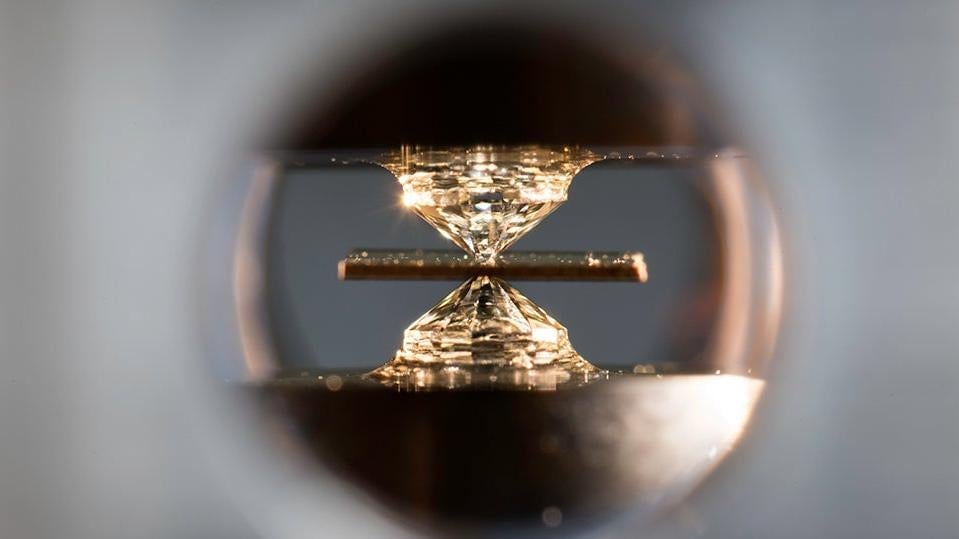

The German scientists centered their efforts on nuclear fission, the process of splitting a heavy atomic nucleus, such as uranium, by bombarding it with neutrons. This process releases a significant amount of energy. Heisenberg’s group, in particular, aimed to induce a chain reaction in uranium submerged in heavy water, hoping to produce plutonium for an atomic bomb. The Nazi reactor cubes, approximately two inches per side, were suspended in a three-dimensional lattice within the heavy water. Fortunately, their design proved unsuccessful, and time ran out for the Nazi nuclear program.

In 1945, Allied forces seized a portion of the uranium cubes used in the German experiments, shipping over 600 to the United States. The fate of some remains unknown, while others, like the cube in Washington, have questionable origins. One cube at the University of Maryland arrived with a note stating, “Taken from the reactor that Hitler tried to build. Gift of Ninninger.” This note alludes to Robert Nininger, an interim manager at a Manhattan Project site, who likely acquired the cube and passed it on, eventually leading it to project collaborator Timothy Koeth.

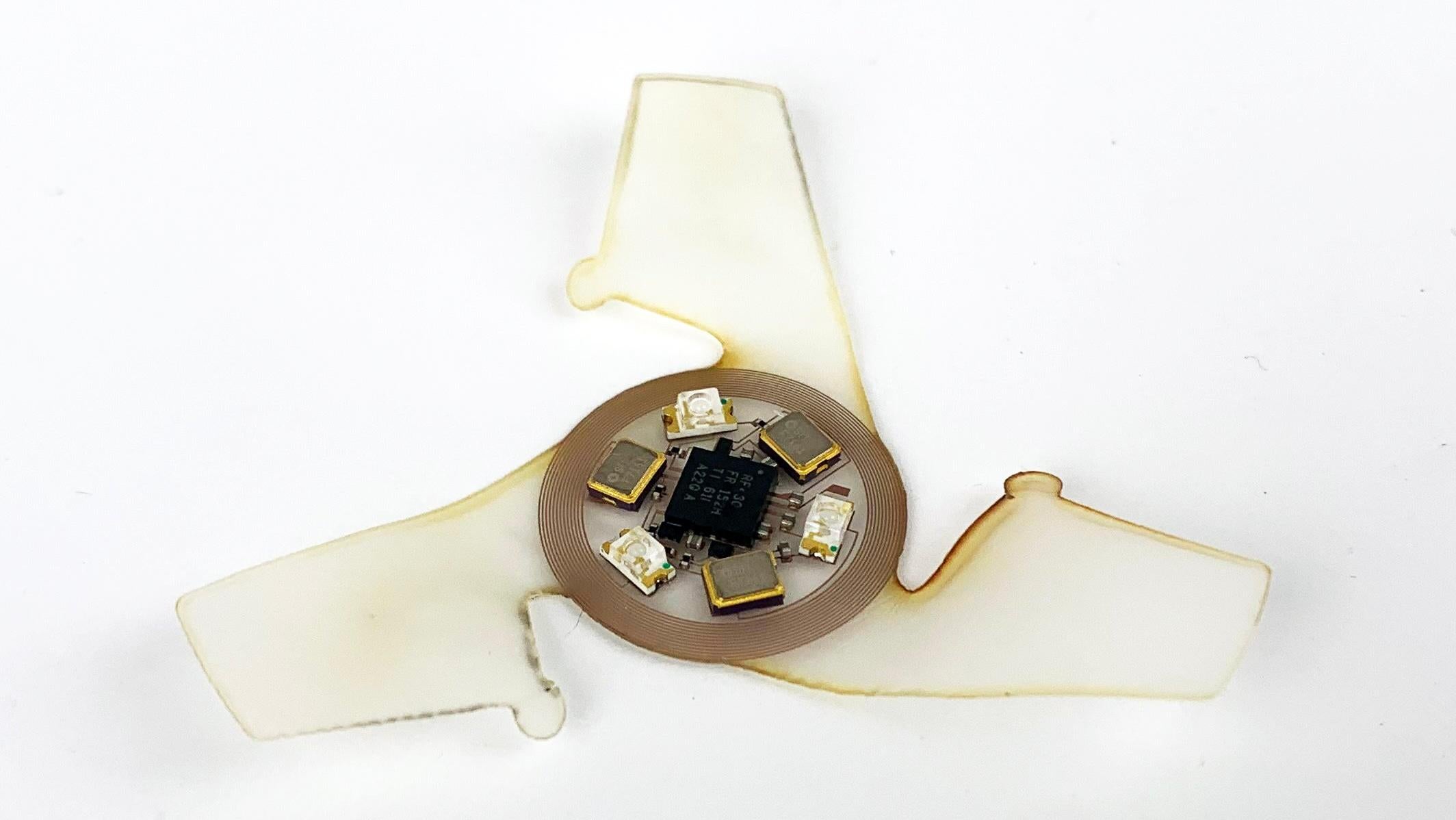

The research team is utilizing radiochronometry, a technique that analyzes radioactive decay to determine the age of materials. By measuring the amounts of thorium and protactinium, decay products of uranium, the researchers can estimate when the cubes were originally cast. Furthermore, impurities within the cubes may reveal traces of rare-earth elements, potentially indicating the geographical source of the uranium ore.

Brittany Robertson, a chemist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, is employing a specialized radiochronometric method to identify each element present in a cube and its concentration. This data will be crucial for pinpointing the manufacturing date.

“Our primary objective is to verify the origin of the three cubes we’re currently analyzing,” Schwantes stated. “We expect their age to be from the early to mid-1940s. If our dating method proves sufficiently precise, we might even be able to discern whether they came from Heisenberg’s or Diebner’s program, as their fabrication dates differed by about a year.”

The short timeframes amenable to radiochronometry allow the researchers to gain insights into the composition and characteristics of the cubes as they were in the 1940s. While tracing a cube back to a specific laboratory remains a challenging “stretch goal,” the team is confident in their ability to at least confirm the cubes’ Nazi origins, a long-held assumption that they are now equipped to rigorously investigate.