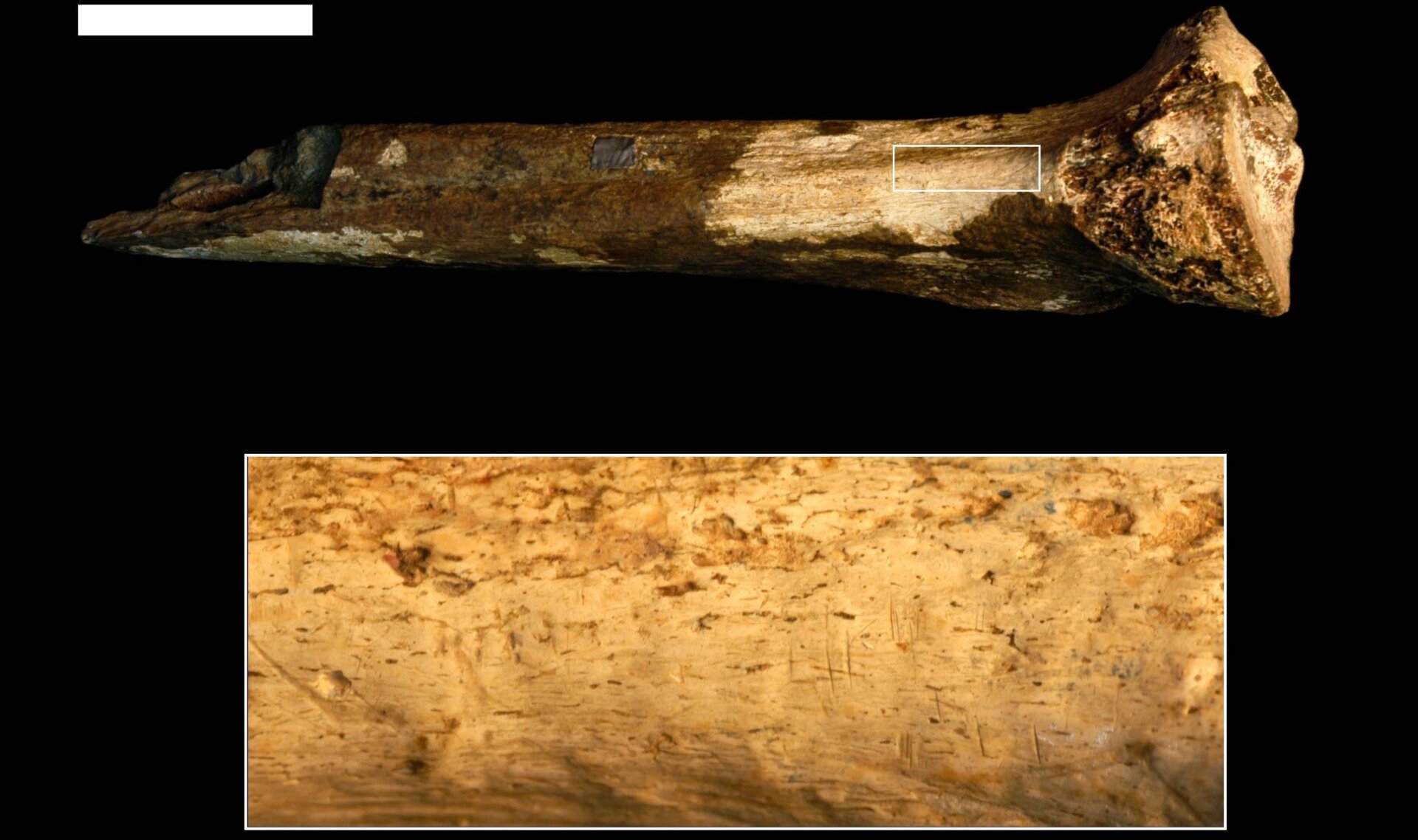

A 1.45 million-year-old tibia discovered in Kenya in 1970 by Mary Leakey may hold the earliest evidence of “systematic cannibalism” among hominins. Recent analysis reveals cut marks on the bone, suggesting the removal of flesh by stone tools. This discovery sheds light on the complex behaviors of our early ancestors.

This ancient tibia, unearthed in Ileret, Kenya, presents a fascinating puzzle. The bone bears a series of small, perpendicular cut marks. While the exact hominin species the tibia belonged to remains unknown, the marks suggest a deliberate act of butchery. Homo sapiens, our own species, wouldn’t emerge for hundreds of thousands of years.

A new study, published in Scientific Reports, details these cut marks, consistent with one hominin species butchering another. “We don’t know who was eaten, nor who did the eating,” explained Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and the study’s lead author. The region of northern Kenya where the tibia was found was home to three different hominin species: Paranthropus boisei, Homo erectus, and Homo habilis. Any of these could have been the tool users responsible for the marks.

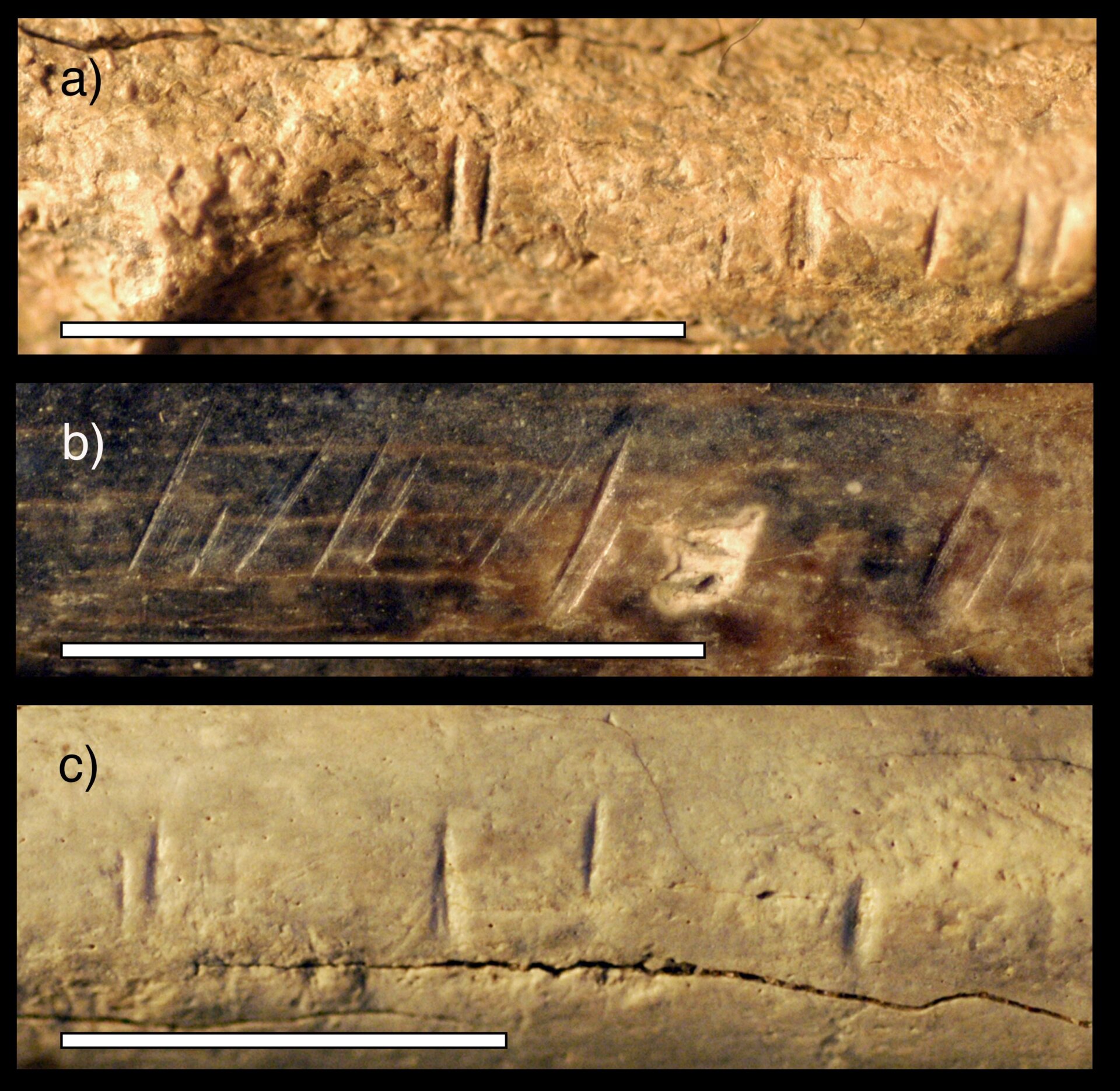

Similar cut marks on (top to bottom) an antelope mandible, an antelope radius, and a mammal scapula.Similar cut marks found on other animal bones (top to bottom: antelope mandible, antelope radius, mammal scapula) compared to the marks on the hominin tibia. Photo: Briana Pobiner

Similar cut marks on (top to bottom) an antelope mandible, an antelope radius, and a mammal scapula.Similar cut marks found on other animal bones (top to bottom: antelope mandible, antelope radius, mammal scapula) compared to the marks on the hominin tibia. Photo: Briana Pobiner

While evidence of cannibalism exists among Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, this tibia may represent a far earlier instance. Previous evidence of cut marks on a hominin fossil, dating between 2.6 and 1.5 million years old, has been disputed, with some arguing the marks resulted from natural processes.

Pobiner examined 199 postcranial hominin fossils at the National Museums of Kenya, many from excavations conducted decades ago by Mary and Louis Leakey. Of these, only the 28th fossil she studied, this tibia, displayed these distinctive cut marks. “I saw this beautifully preserved patch of bone,” Pobiner recalled. “The marks were immediately recognizable. I’ve seen them on hundreds of animal fossils, but never a hominin.”

Pobiner created molds of the marks and sent them to Michael Pante, a paleoanthropologist at Colorado State University, for independent analysis. Pante compared the scans against a database of nearly 900 similar marks.

Stone tools, a hallmark of hominin technology, date back over three million years. These tools were used to create various types of butchery marks: skinning marks, disarticulation marks, and defleshing marks. The marks on the tibia were identified as defleshing marks, indicating the removal of flesh for consumption.

Due to the inability to identify the species involved, researchers hesitate to definitively label this as cannibalism, which specifically refers to the consumption of a member of one’s own species. However, the possibility remains strong.

Michael Petraglia, director of the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution, commented, “This study is exemplary, demonstrating how new behavioral information can be gleaned from old museum collections using modern techniques.” He cautioned, however, that “we should be cautious, as this is an isolated fossil, and we cannot be certain which hominin species processed the tibia.” He also noted that the cut marks don’t definitively indicate whether the butchery was for nutritional or ritualistic purposes.

The tibia also bears tooth marks consistent with those of large carnivores, possibly saber-toothed cats that inhabited the region. Whether the hominin was scavenged after a big cat kill or vice versa remains uncertain. Further clarification, Pobiner quipped, would require “a time machine.”

This discovery offers a glimpse into the complex interactions and survival strategies of early hominins, raising intriguing questions about their behavior and dietary practices. While definitive answers remain elusive, the 1.45 million-year-old tibia provides valuable insights into our evolutionary past.