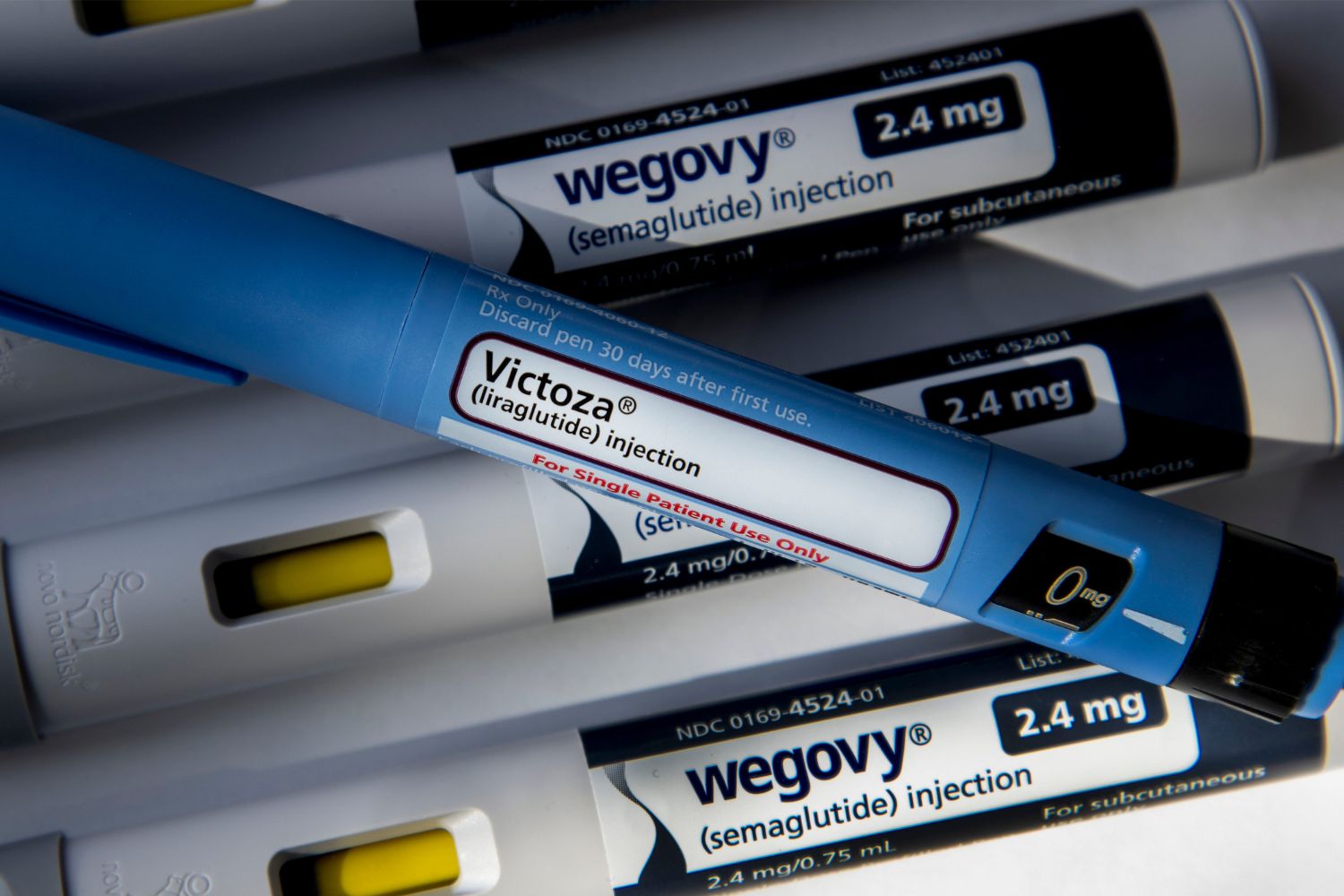

Sneezing and coughing, while both respiratory reflexes aimed at expelling irritants and pathogens, have long been assumed to share common neural pathways. New research challenges this assumption, revealing distinct mechanisms governing these seemingly similar actions. This discovery holds significant potential for developing targeted treatments for respiratory ailments.

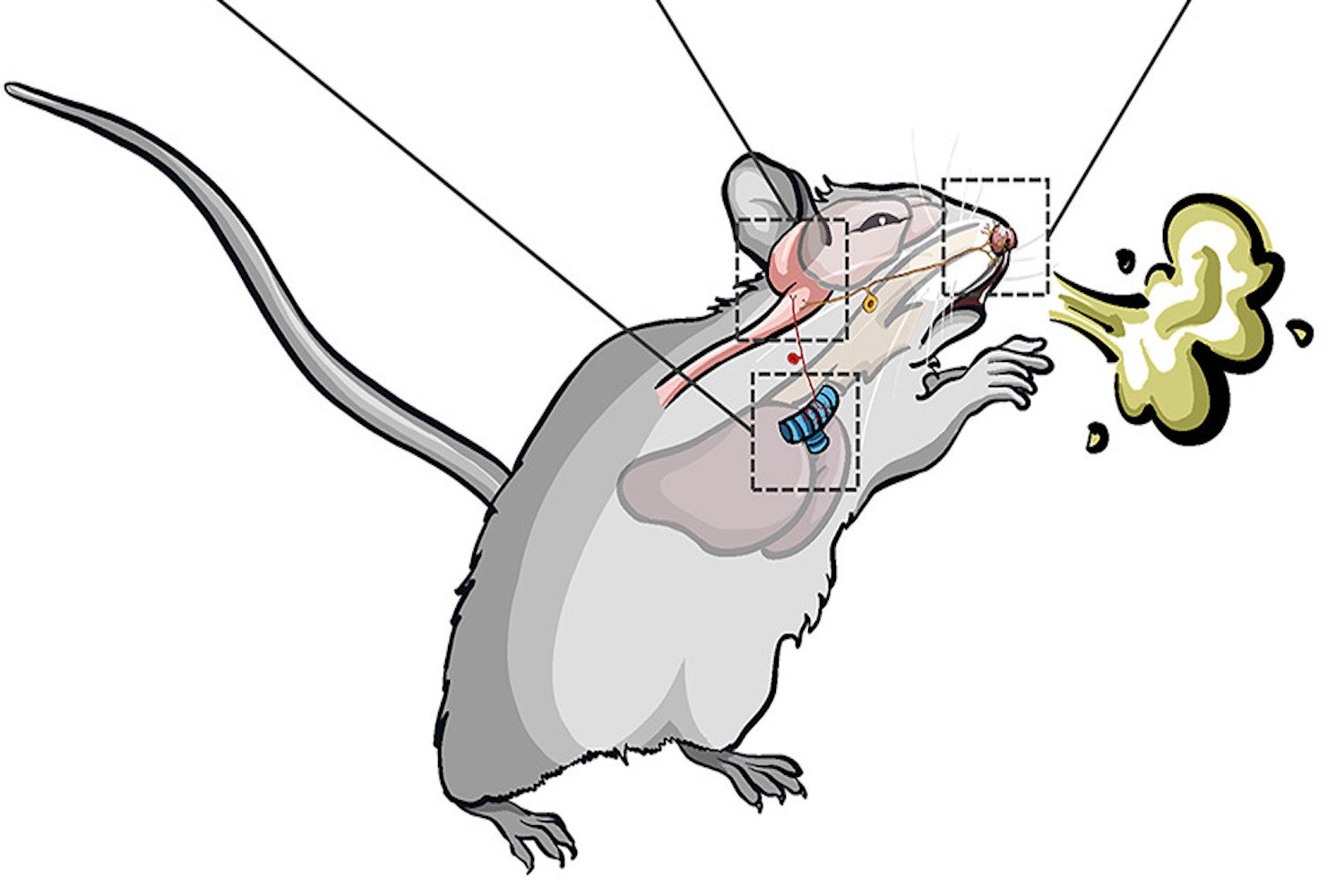

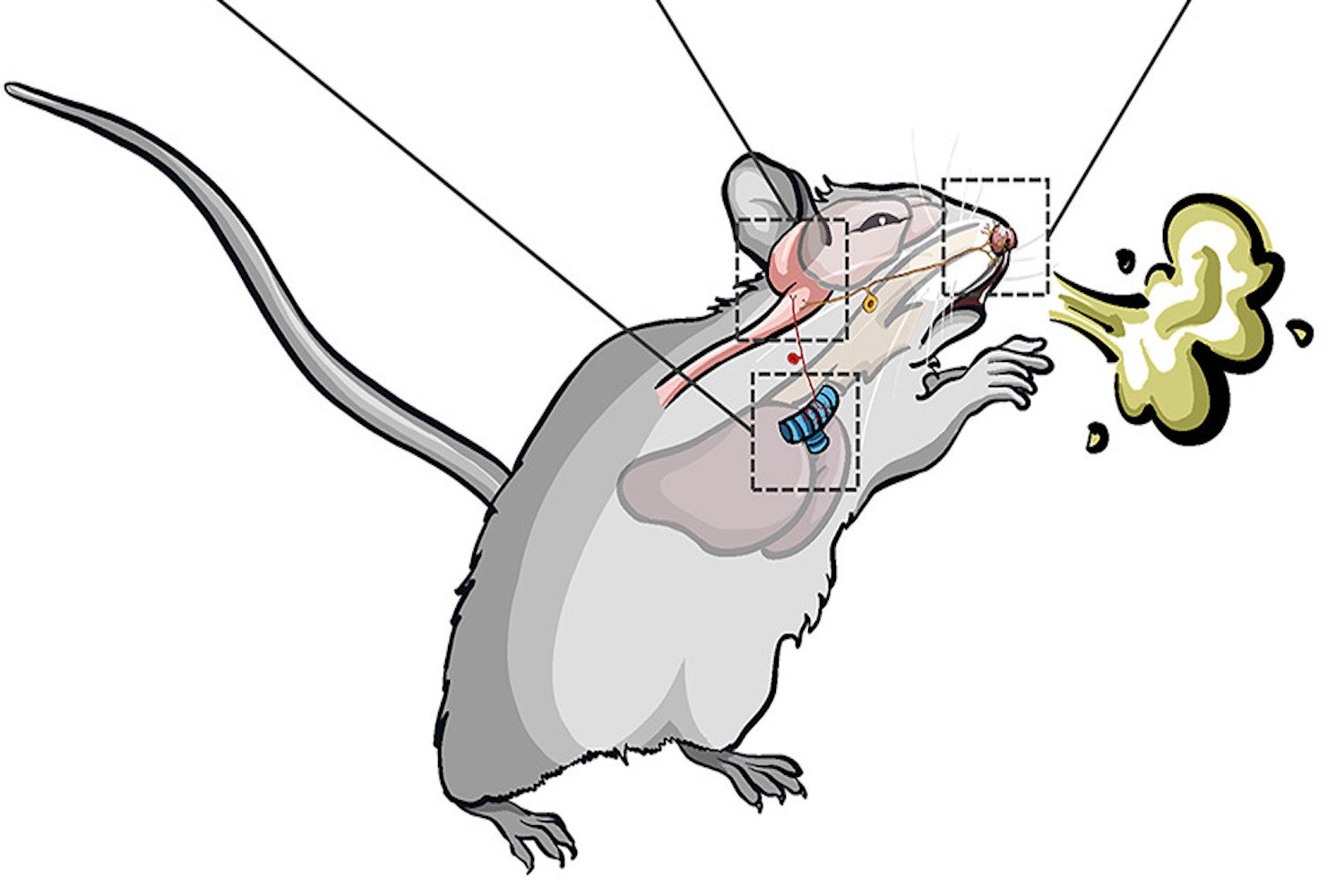

A recent study published in Cell by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis sheds light on these distinct mechanisms. The team, led by anesthesiologist Haowu Jiang, investigated the neural pathways involved in sneezing and coughing in mice. By stimulating specific nasal passage neurons known to react to conditions associated with sneezing, such as cold or itch sensations, they pinpointed the neurons responsible for triggering a sneeze. They discovered that while several neuronal sets can activate the nasal passage lining, only the stimulation of a specific itch receptor, MrgprC11, resulted in a sneeze.

alt text: A microscopic image of a mouse's nasal passage with highlighted MrgprC11 receptors

alt text: A microscopic image of a mouse's nasal passage with highlighted MrgprC11 receptors

To further validate their findings, the researchers studied mice infected with the influenza virus. Mice with deactivated MrgprC11 receptors still experienced the illness and coughed, but were unable to sneeze. Interestingly, attempts to induce coughing by stimulating tracheal MrgprC11 neurons resulted only in tracheal irritation, not coughing. This suggests that coughing is linked to an entirely different set of neurons. The researchers concluded that “at the circuit level, sneeze and cough signals are transmitted and modulated by divergent neuropathways.”

An unexpected outcome of the research was the confirmation that mice can indeed cough. While debated among scientists, the Washington University team definitively identified the auditory and respiratory patterns associated with coughing in mice.

alt text: Graphical representation of the distinct neural pathways involved in sneezing and coughing

alt text: Graphical representation of the distinct neural pathways involved in sneezing and coughing

While both sneezing and coughing expel microbes and fluids, the revelation of their distinct underlying mechanisms is significant. Although further research is needed to determine if these pathways exist in humans, the study’s findings hold promise for the development of new drugs and symptom-specific treatments for respiratory infections and allergies. This could lead to more effective relief from colds and allergies, minimizing the unpleasant side effects associated with current medications like antihistamines and corticosteroids, such as dryness, bleeding, and infections. This advancement could be a significant improvement for those suffering from respiratory ailments.