Liraglutide, a drug similar to the popular diabetes and weight loss medication semaglutide, has shown promising results in a recent clinical trial for Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers at Imperial College London found evidence suggesting that liraglutide may reduce brain shrinkage and slow cognitive decline in individuals with early-stage Alzheimer’s. This exciting development comes as semaglutide itself is undergoing larger Phase III trials for the same neurodegenerative condition.

Liraglutide belongs to a class of drugs known as GLP-1 receptor agonists, which mimic the naturally occurring hormone GLP-1. GLP-1 helps regulate blood sugar and appetite. Liraglutide was initially approved for treating type 2 diabetes in 2010 and later for obesity in 2014. The connection between poorly controlled diabetes and an increased risk of Alzheimer’s, coupled with animal studies suggesting liraglutide’s potential neuroprotective effects, prompted the Imperial College London team to investigate its use in Alzheimer’s patients.

The double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involved 204 patients diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s. Half received liraglutide, while the other half received a placebo. While the study’s primary outcome, changes in brain glucose metabolism, showed no significant difference between the two groups, other findings were encouraging. Patients receiving liraglutide experienced a nearly 50% slower rate of brain volume loss compared to the placebo group over a year. Furthermore, their cognitive decline was approximately 18% slower. These findings were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

It’s important to note that this research is preliminary and has not yet been peer-reviewed. Even if the results hold up to scrutiny, the exact mechanism by which liraglutide exerts its potential benefits remains unclear. Researchers speculate on several possibilities, including reduced inflammation, improved insulin resistance, mitigation of toxic Alzheimer’s biomarkers, and enhanced nerve cell communication within the brain.

“We think liraglutide is protecting the brain possibly by reducing inflammation, lowering insulin resistance and the toxic effects of Alzheimer’s biomarkers or improving how the brain’s nerve cells communicate,” explained Paul Edison, a professor of neuroscience at Imperial’s Department of Brain Sciences, in a statement from the university.

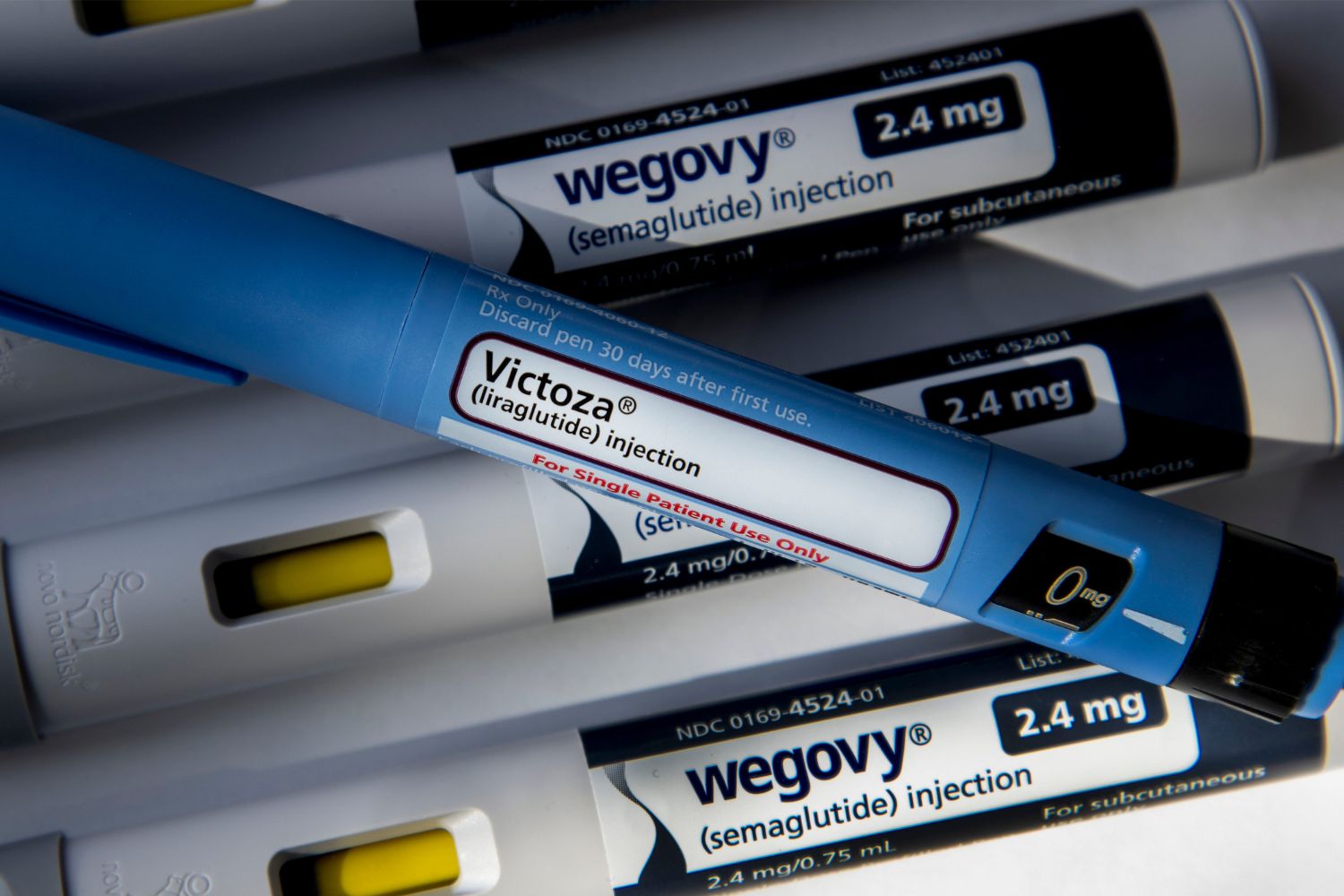

The emergence of even more potent GLP-1 drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) since the study’s commencement adds another layer of intrigue. These newer medications have demonstrated superior efficacy in managing diabetes and obesity compared to older GLP-1 agonists like liraglutide. A recent study even found that semaglutide can improve brain health in people with type 2 diabetes.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/ozempic-injection-closeup-170209556-9f2c3867178345a9a873c57f4c43be41.jpg”>https://www.verywellhealth.com/thmb/V3v7J-j88D613Y2hP439RjX7kI=/1500×0/filters:no_upscale():max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/ozempic-injection-closeup-170209556-9f2c3867178345a9a873c57f4c43be41.jpg)

Novo Nordisk, the manufacturer of both liraglutide and semaglutide, is currently conducting two large-scale, placebo-controlled trials to evaluate semaglutide’s impact on early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. If these trials, expected to conclude within the next few years, yield positive results, GLP-1 drugs could become valuable additions to the growing arsenal of Alzheimer’s treatments.