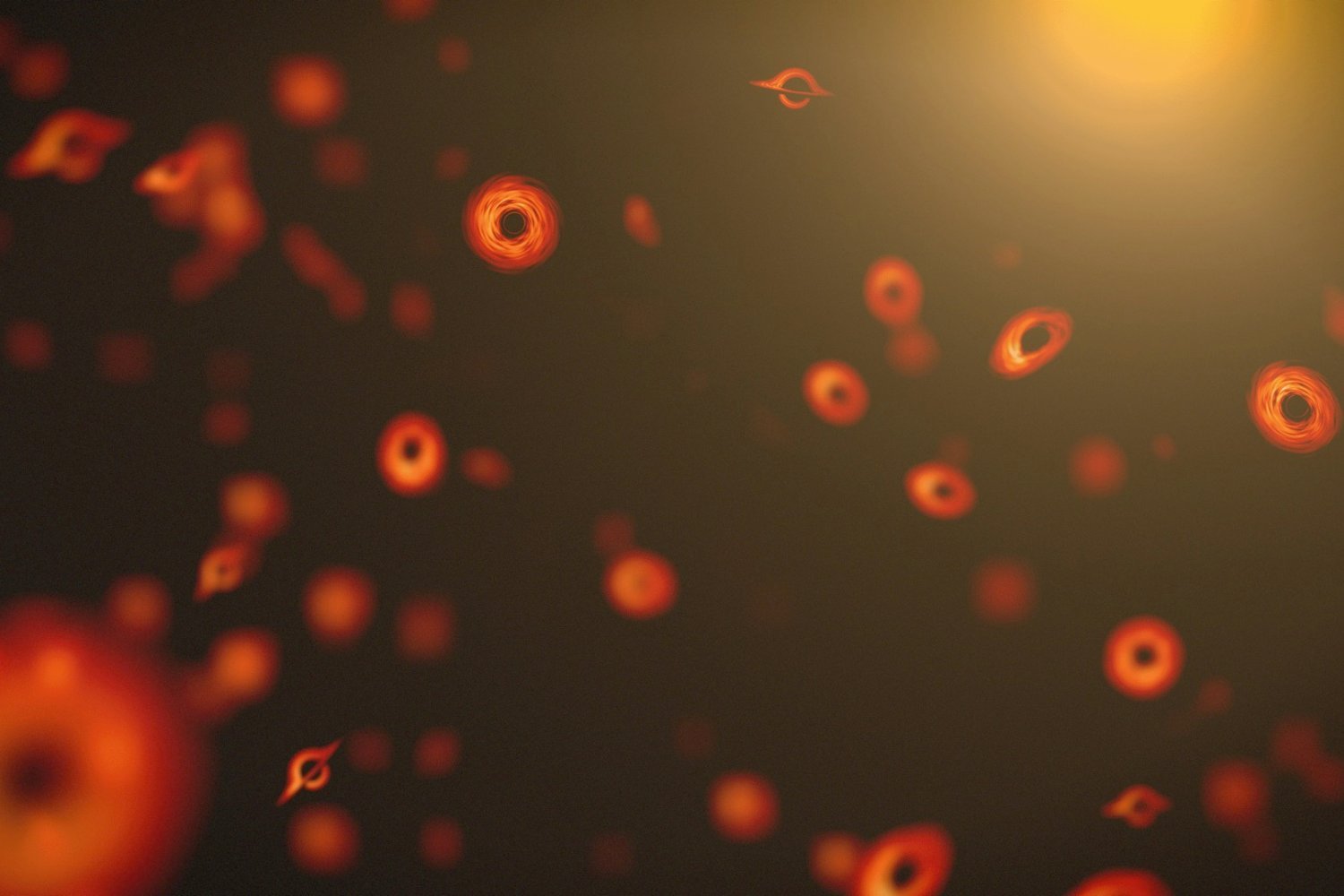

Black holes, some of the universe’s most enigmatic objects, are so gravitationally powerful that even light cannot escape their grasp, making them incredibly challenging to study. Recent research has proposed a fascinating, if vexing, theory: that minuscule black holes from the universe’s infancy could account for dark matter, the invisible substance comprising a significant portion of the cosmos.

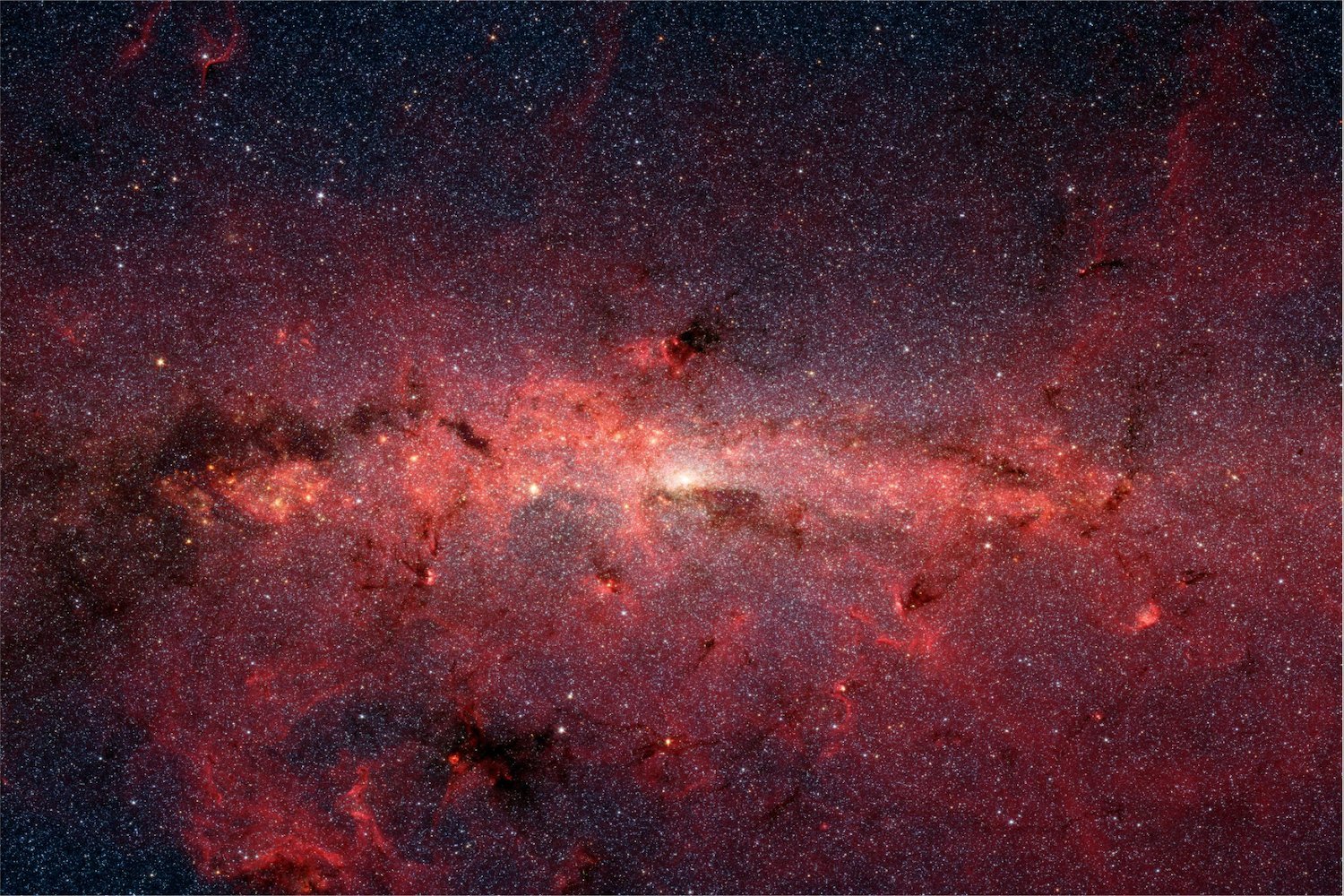

Dark matter constitutes approximately 27% of the universe’s mass, yet remains undetectable by current scientific instruments. Its presence is inferred through its gravitational influence on observable objects, such as galaxy clusters. Several candidates for dark matter exist, including dark photons, axions, and Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs). Primordial black holes, tiny black holes formed in the early universe, are another compelling contender. These hypothetical objects traverse space, remaining largely invisible due to the lack of significant orbiting matter.

Primordial Black Holes: A Deep Dive

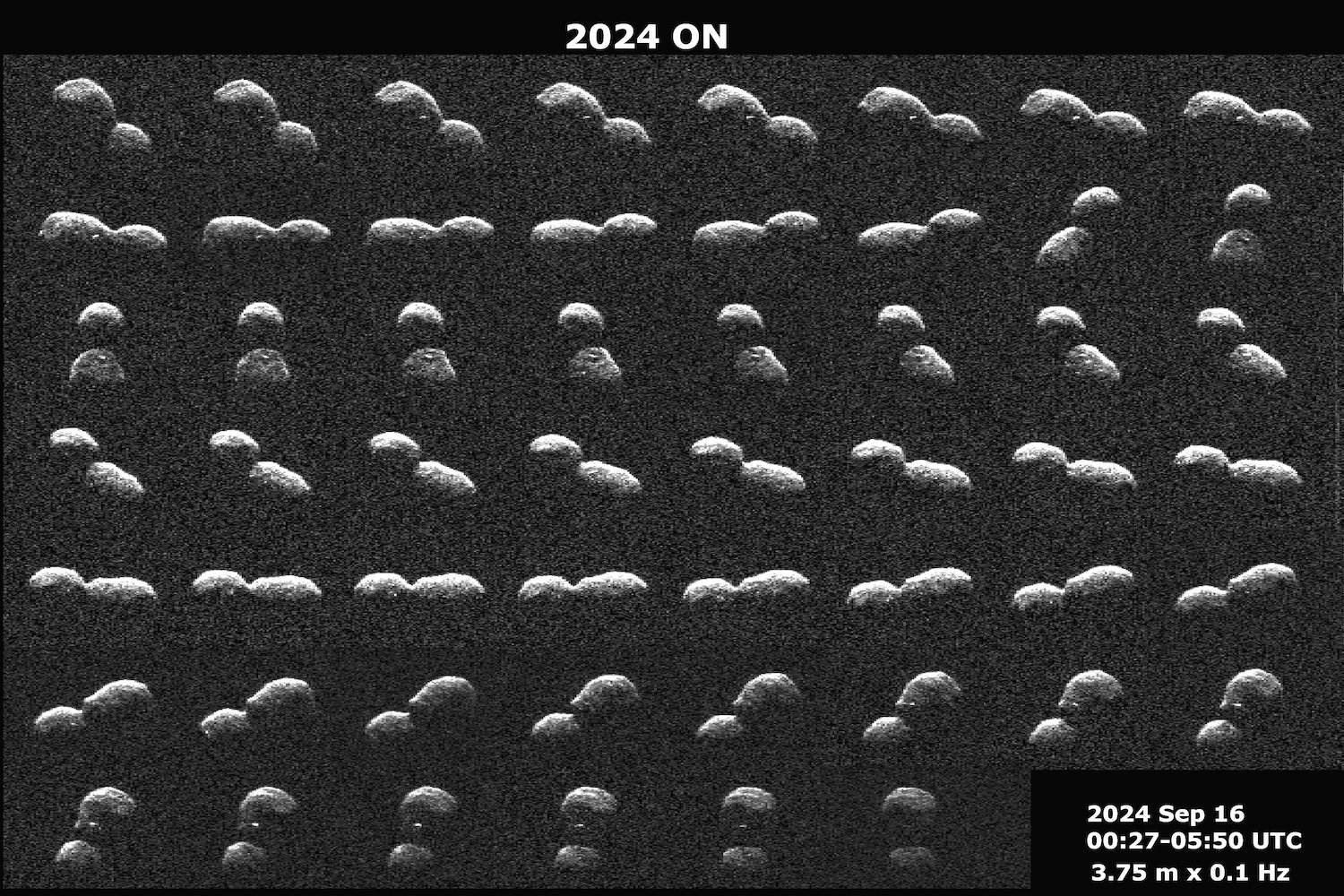

A study published in Physical Review D suggests the abundance of primordial black holes could be substantial enough for at least one to pass through our inner solar system every decade. The team posits that these flyby events would be detectable as gravitational waves. This research aligns with recent findings from another team suggesting dark matter signatures might be concealed within gravitational wave data from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).

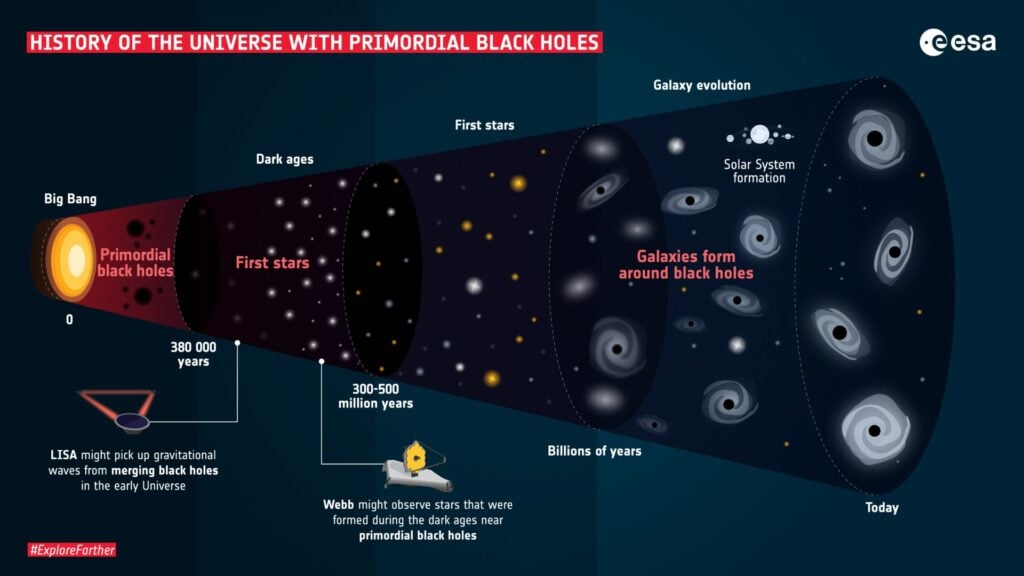

A graphic showing when primordial black holes may have formed, and instruments that can detect black holes. Graphic: ESAA timeline illustrating the potential formation of primordial black holes alongside the instruments capable of detecting them. (Graphic: ESA)

A graphic showing when primordial black holes may have formed, and instruments that can detect black holes. Graphic: ESAA timeline illustrating the potential formation of primordial black holes alongside the instruments capable of detecting them. (Graphic: ESA)

The term “primordial” refers to black holes theorized to have formed during the universe’s initial moments. Random fluctuations in density may have caused pockets of matter to collapse, creating these relatively small, lightless entities. Observed black holes range from stellar-mass (roughly the size of our Sun) to supermassive black holes billions of times larger. An asteroid-sized primordial black hole, therefore, is minuscule in comparison, with some potentially even as small as an atom.

Detecting the Undetectable

Sarah Geller, a theoretical physicist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and co-author of the study, clarified to LiveScience that the research does not definitively claim the existence of primordial black holes, their composition of dark matter, or their presence in our solar system. Instead, the team’s hypothesis suggests that if these conditions were true, one such object could traverse our inner solar system every one to ten years.

The Future of Primordial Black Hole Research

With new gravitational wave detections occurring regularly and the development of LISA, a next-generation space-based gravitational wave observatory, the prospect of detecting primordial black holes is becoming increasingly tangible. These advancements mark an exciting era in the search for dark matter and the enigmatic primordial black holes that may hold the key to understanding its nature.