Oldowan tools, among the earliest in archaeological history, crafted from readily available stones, enabled hominins to thrive in challenging environments. Researchers recently unearthed Oldowan tools in southwestern Kenya dating back 2.9 to 2.58 million years, expanding the known range of this technology. The discovery also included numerous animal bones and Paranthropus teeth, an early hominin, suggesting Homo may not have been the sole toolmaker. One molar is the largest hominin tooth ever recorded. The findings are published in Science.

“The Oldowan toolkit originated in East Africa, spreading across the continent and eventually reaching as far as China. It represents the first persistent and widespread technology,” explains Thomas Plummer, a paleoanthropologist at Queens College and the study’s lead author, in an interview with MaagX. “For those interested in human adaptation and our reliance on technology, this discovery provides valuable insights into the relationship between our ancestors and their tools.”

Magnetostratigraphy, a dating technique based on Earth’s magnetic field reversals, places the tools between 3 and 2.58 million years old. Uranium-Thorium dating of sediment apatite crystals yielded more precise ages of 2.87 ± 0.79 and 2.98 ± 0.5 million years, suggesting the site is likely closer to the older end of the estimated range.

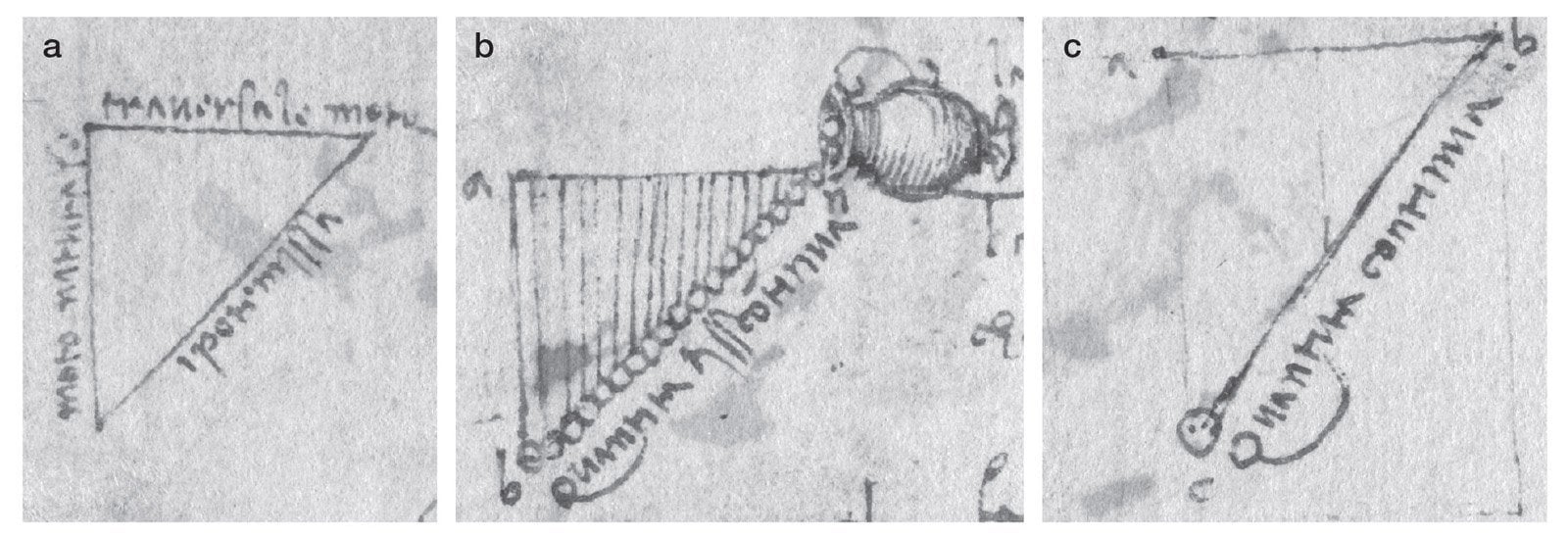

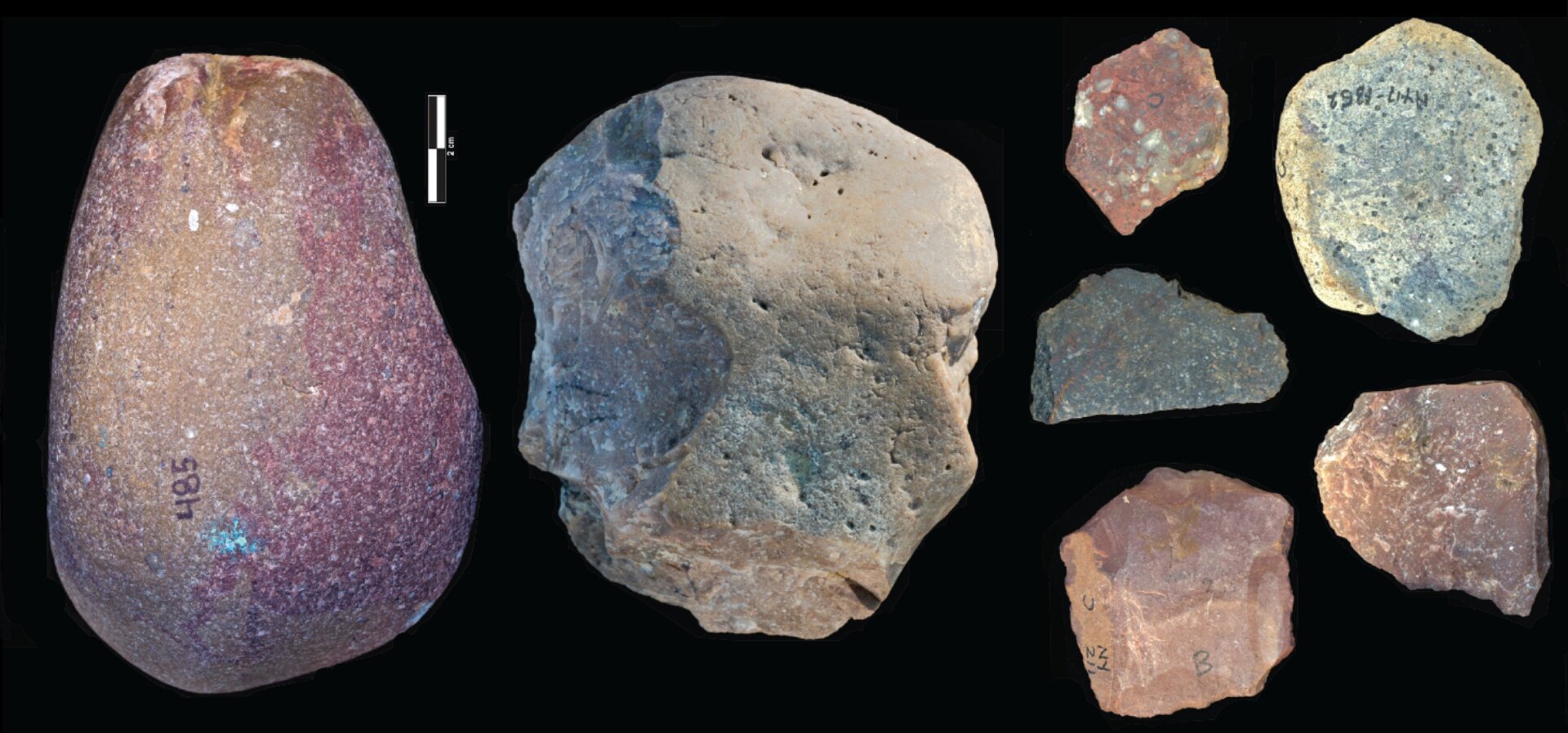

Part of the Oldowan toolkit found at Nyayanga.

Part of the Oldowan toolkit found at Nyayanga.

While earlier, simpler tools dating back 3.3 million years were discovered in Kenya in 2011 and 2012, the Nyayanga tools are nearly as old and suggest hominins beyond early Homo might have utilized this technology.

“The long-held assumption is that only the genus Homo, to which humans belong, could create stone tools,” states Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “But finding Paranthropus alongside these tools presents an intriguing mystery.”

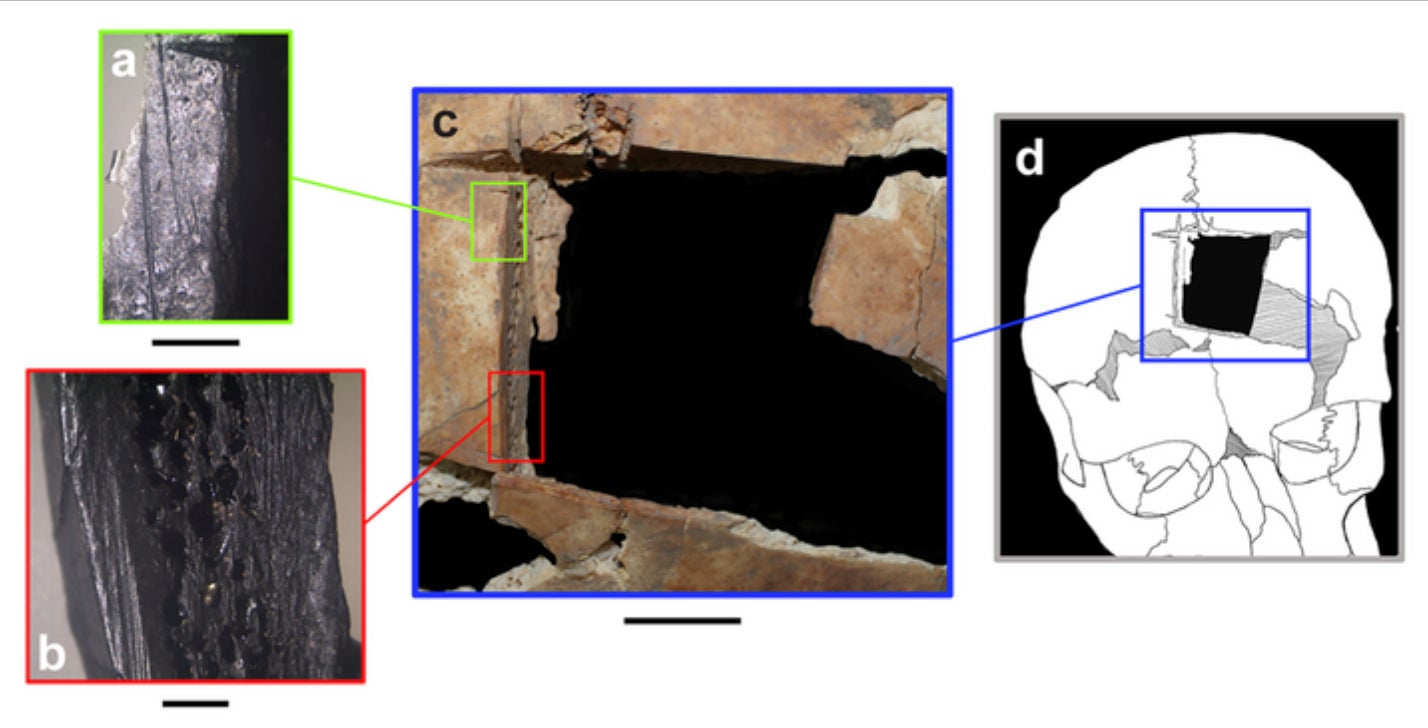

Paranthropus, an extinct hominin, possessed a wide face and powerful teeth adapted for chewing. Despite being smaller than a gorilla, Paranthropus had larger teeth than any primate, Plummer explains. Two Paranthropus molars were discovered at Nyayanga, one being the largest ever found.

Isotopic analysis of the teeth reveals a diet rich in grasses and herbaceous plants. Other hominin remains from the same period indicate similar diets, suggesting these ancestors occupied comparable open ecosystems in ancient Africa.

A Paranthropus molar found at the site.

A Paranthropus molar found at the site.

The Nyayanga site yielded more than just teeth and tools. Across two excavation sites on Lake Victoria’s eastern shore, 1,776 bones were unearthed, including worked bones of hippos and bovids, along with remains of animals likely inhabiting the lakeshore environment, such as turtles, rats, saber-tooth cats, monkeys, and crocodilians.

Cut marks and evidence of crushing and slicing on hippo and antelope bones indicate butchering by hominins. While the specific species responsible remains unidentified, the presence of Paranthropus bones is significant. With the first evidence of fire appearing much later, the meat was likely consumed raw.

The Nyayanga discoveries predate other sites showing evidence of megafauna butchering and plant processing by at least 600,000 years. They also precede the increase in Homo brain size around 2 million years ago.

“East Africa wasn’t a stable cradle for our ancestors,” Potts explains. “It was a volatile environment with fluctuating rainfall, droughts, and a constantly changing food supply.”

The Nyayanga findings challenge previous assumptions about hominin capabilities. As research methods advance and more sites are explored, our understanding of human evolution and our extinct relatives is likely to become increasingly complex.