A remarkable discovery has been made in the Trave River in northern Germany: a 375-year-old shipwreck resting nearly 36 feet below the surface. After an eight-month investigation, researchers from Kiel University have revealed that the Hanseatic vessel sank with 150 barrels of quicklime.

The age of the ship was meticulously determined through independent dating of its timbers in three separate laboratories, confirming its construction in the mid-17th century. Archaeologist Fritz Jürgens, leading the research team, expressed his excitement at the unexpected find. Quicklime, the ship’s cargo, was a crucial material during that period, primarily used in the production of mortar and plaster for construction projects. Preliminary findings suggest the ship met its fate after running aground on a river bend, causing irreparable damage that led to its sinking and subsequent obscurity.

The discovery was a stroke of luck during routine river measurements conducted by the local waterway and shipping authority. Using a multibeam echosounder, a sonar technology employed for mapping waterway bottoms, workers detected an anomaly that prompted further investigation.

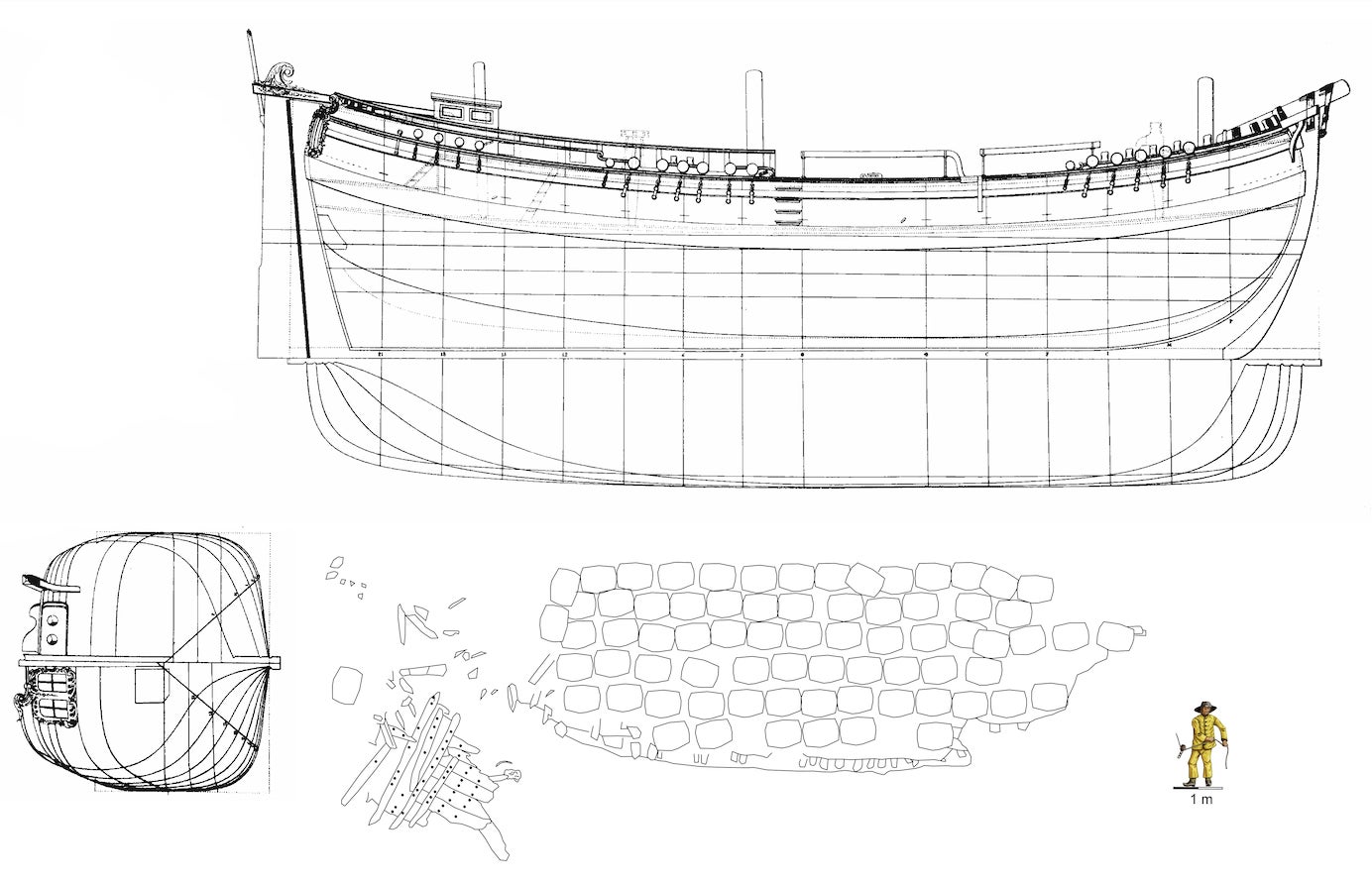

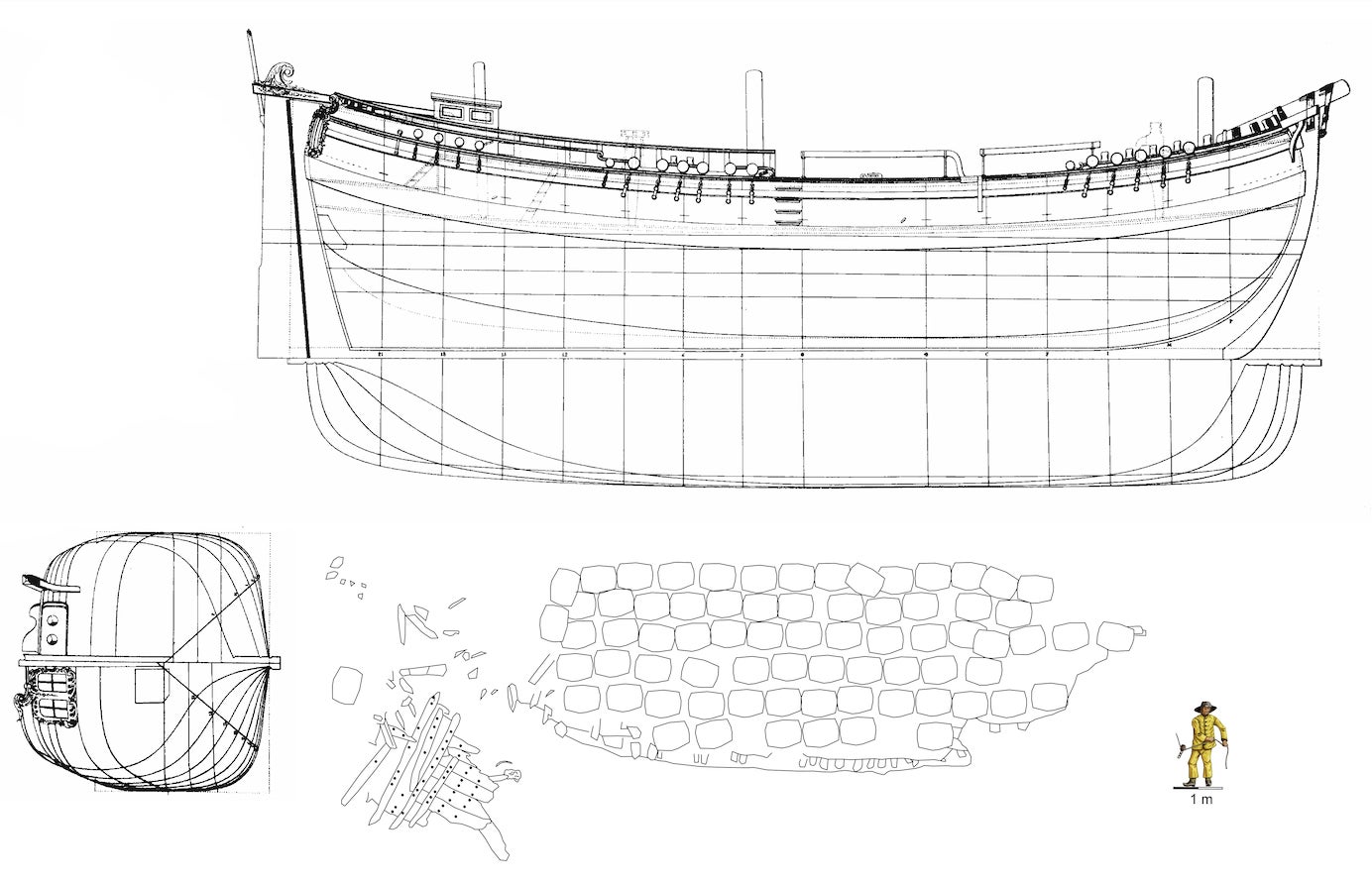

A graphic depicting the probable construction of the ship and the layout of the wreck.

A graphic depicting the probable construction of the ship and the layout of the wreck.

Today, the remnants of the vessel consist primarily of mussel-covered wooden beams and the solidified quicklime cargo. Archaeologists estimate the ship’s original length to be between 65 and 82 feet, classifying it as a medium-sized cargo ship typical of the Baltic Sea trade routes during that era.

While the wreck’s predominantly wooden composition makes it less attractive to salvagers seeking metal scrap, it faces different threats. Thirteen dives to the site revealed that the exposed timbers and cargo are vulnerable to erosion and shipworm infestation. Shipworms, a group of mollusks notorious for consuming wooden structures in marine environments, pose a significant risk to the wreck’s preservation.

The shipwreck’s location in a busy shipping channel exposes it to constant activity, unlike the protected environment of the Weddell Sea where the remarkably preserved Endurance was discovered. This constant activity, along with the erosion and shipworm activity, likely contributes to the limited remains.

The level of oxygen in the water plays a crucial role in the preservation of shipwrecks. Lower oxygen levels slow down the degradation of organic materials. This explains the remarkable preservation of the world’s oldest known intact shipwreck, a 2,400-year-old Greek merchant ship resting on the Black Sea floor.

A graphic depicting the probable construction of the ship and the layout of the wreck.

A graphic depicting the probable construction of the ship and the layout of the wreck.

To protect this historical find, the archaeological team is collaborating with the City of Lübeck and other institutions. They are exploring options, including salvaging the wreck and preserving its remains above water for better management and conservation.