Researchers have unearthed what they believe to be the oldest fossilized skin ever discovered, tucked away within a limestone cave system in Oklahoma. Dating back to the early Permian Period, between 289 and 286 million years ago, this remarkable find offers a glimpse into the early evolution of terrestrial vertebrates.

The fossilized skin, smaller than a fingernail, belonged to an ancient reptile and represents the epidermis—the protective outer layer found in amniotes, a group encompassing reptiles, mammals, and birds. This discovery, along with other fossils from the same cave system, is detailed in a study published in Current Biology. The find marks the first known skin-cast fossil from the Paleozoic Era.

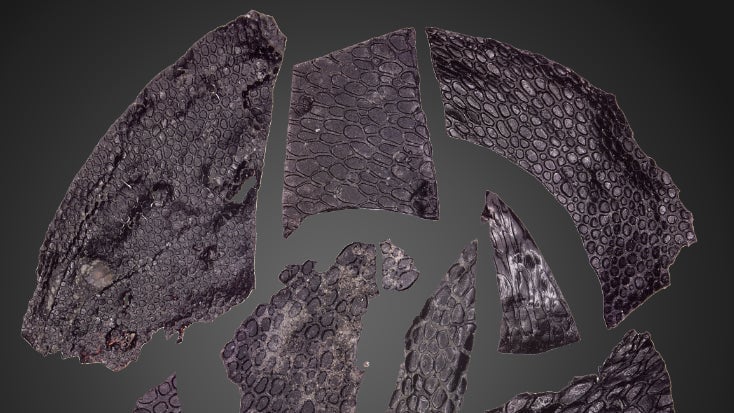

The cave also yielded other significant finds, including compressed skin fragments, pieces of skin from the ancient reptile Captorhinus aguti, and scales from anamniotes—aquatic-reproducing animals. While the C. aguti skin fragments originated from the area just behind the reptile’s head, not all amniote skin samples could be definitively linked to specific creatures.

Two Captorhinus aguti, whose skin was also discovered in the Oklahoma cave system.Two Captorhinus aguti, whose skin fossils were part of the recent discovery. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Two Captorhinus aguti, whose skin was also discovered in the Oklahoma cave system.Two Captorhinus aguti, whose skin fossils were part of the recent discovery. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The epidermis, while often overlooked, plays a crucial role in protecting the body from external threats. This outermost skin layer maintains hydration and shields against bacteria, temperature extremes, and other environmental hazards. The ancient reptilian skin examined in this study, originally recovered from the cave and donated by Bill and Julie May, appears to have served a similar protective function for its host.

The remarkable preservation of the skin and other fossils within the cave is attributed to a unique set of circumstances. Animals likely fell into the cave system during the early Permian and were buried in fine clay sediments, which slowed the decomposition process. Crucially, the cave system was also an active oil seepage site during the Permian. The interaction between hydrocarbons in the petroleum and tar likely contributed to the exceptional preservation of the skin.

Microscopic examination reveals similarities between the ancient skin’s surface and that of modern crocodiles, with scale hinges resembling those found in present-day snakes and worm lizards. This morphology, coupled with the skin’s exceptional age, suggests that this crucial organ for terrestrial vertebrate life was already established during the early diversification of amniotes.

The study of ancient reptiles continues to provide valuable insights into evolutionary history. In 2022, a 150-million-year-old fossil from Wyoming shed light on the evolutionary timeline of rhynchocephalians, a unique reptile group with only one surviving member: the tuatara. The recently analyzed skin, being roughly twice as old, underscores the vastness of deep time.

This discovery highlights the importance of paleontological research in understanding the evolution of life on Earth. The fossilized skin provides a rare window into the early Permian Period and offers crucial evidence for the development of the epidermis in ancient reptiles. Further research may reveal additional details about the biology and environment of these fascinating creatures.