The extinct Otodus megalodon, a colossal shark that dominated the Miocene oceans, has long captivated our imaginations. Its estimated length of up to 60 feet, three times the size of the largest great white sharks, has solidified its legendary status. However, recent research suggests that this ancient apex predator may have had a more slender physique than previously believed.

O. megalodon disappeared from the fossil record around 3.6 million years ago. Newborn megalodons were already an impressive 6 feet long, and there’s evidence suggesting they may have even preyed on their siblings. Previous studies estimated adult lengths between 50 and 65 feet (15-20 meters).

A new study published in Palaeontologia Electronica challenges the traditional view of O. megalodon‘s bulk. By analyzing discrepancies in previous length calculations of a single O. megalodon specimen, the researchers propose a more streamlined body shape, less bulky than the modern great white shark.

Since O. megalodon remains are largely fragmentary, consisting mainly of fist-sized teeth and vertebrae, paleontologists have relied on its living relative, the great white shark, as a model for reconstructing its dimensions.

“The great white shark was the primary model for O. megalodon‘s body form, primarily because both were thought to be fast-swimming, ‘warm-blooded’ sharks,” explains Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist at DePaul University in Chicago and co-author of the study.

However, recent discoveries have shifted this perspective. While O. megalodon‘s warm-bloodedness has been confirmed, research has also revealed that the slow-moving basking shark is also warm-blooded, suggesting that warm-bloodedness doesn’t necessarily equate to a fast-swimming lifestyle. Further research on O. megalodon scales, co-authored by Shimada, indicates that the giant predator was likely a slower swimmer, possibly relying on short bursts of speed during hunts.

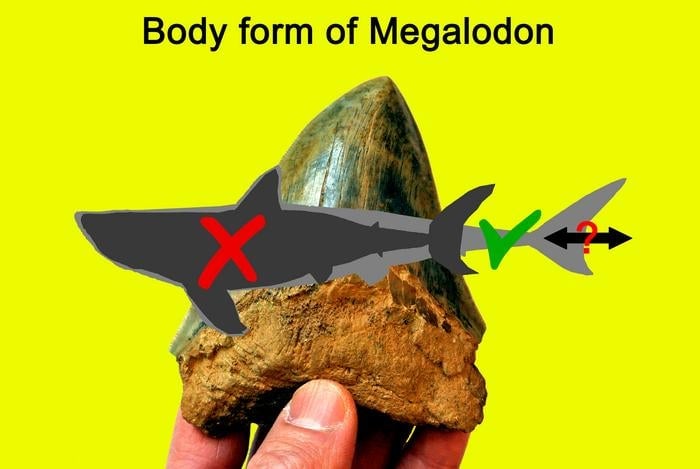

A graphic showing how O. megalodon’s body shape may differ from previous assumptions.A revised depiction of O. megalodon, suggesting a slimmer build than previous estimations. (Graphic: DePaul University/Kenshu Shimada)

A graphic showing how O. megalodon’s body shape may differ from previous assumptions.A revised depiction of O. megalodon, suggesting a slimmer build than previous estimations. (Graphic: DePaul University/Kenshu Shimada)

Philip Sternes, a biologist at the University of California, Riverside, and co-author of the new paper, suggests the mako shark might be a more appropriate model for O. megalodon‘s shape. The shortfin mako, the ancient shark’s closest living relative, is known for its slender build and remarkable speed, reaching up to 46 miles per hour (74 kilometers per hour) in short bursts.

“Our study encourages a more innovative approach to understanding O. megalodon‘s biology,” Shimada states. While still a massive creature, the new research suggests a more elongated, less bulky physique, perhaps akin to a prehistoric oceanic equivalent of a basketball player like Victor Wembanyama. Sternes adds that this leaner build may imply less frequent feeding than previously thought.

Food availability is a leading hypothesis for O. megalodon‘s extinction. Research suggests competition with great white sharks may have played a role, potentially outcompeting their larger relatives and claiming the title of the largest lamniform shark.