Recent archaeological discoveries at Ta’ab Nuk Na, a submerged Maya salt production site off the coast of Belize, suggest that ancient workers lived on-site and potentially collaborated in family-based teams. This significant finding sheds new light on the organization and scale of salt production within the Maya civilization.

This largest of 110 submerged Maya sites in Paynes Creek National Park dates back to 600-800 CE, during the Late Classic period. The analysis of the site’s operations is detailed in a study published in the journal Antiquity. The research reveals compelling evidence of a residential building and three associated salt kitchens located in the shallow waters amid a red mangrove forest.

“The discovery of a residence at the site indicates the salt workers were living there, rather than commuting daily or seasonally,” explained Heather McKillop, lead author of the study and an archaeologist at Louisiana State University. This suggests a more permanent and specialized workforce dedicated to salt production.

The headless ocarina in the shape of a human.A headless ocarina, shaped like a human, found at the site. (Photo: McKillop et al., Antiquity 2022)

The headless ocarina in the shape of a human.A headless ocarina, shaped like a human, found at the site. (Photo: McKillop et al., Antiquity 2022)

The Maya primarily produced salt through two methods: evaporating saltwater and boiling brine in briquetage, a type of coarse ceramic vessel. The latter method was extensively employed at Ta’ab Nuk Na. Salt played a vital role in Maya society, used for preserving food, cooking, and potentially even as a form of currency.

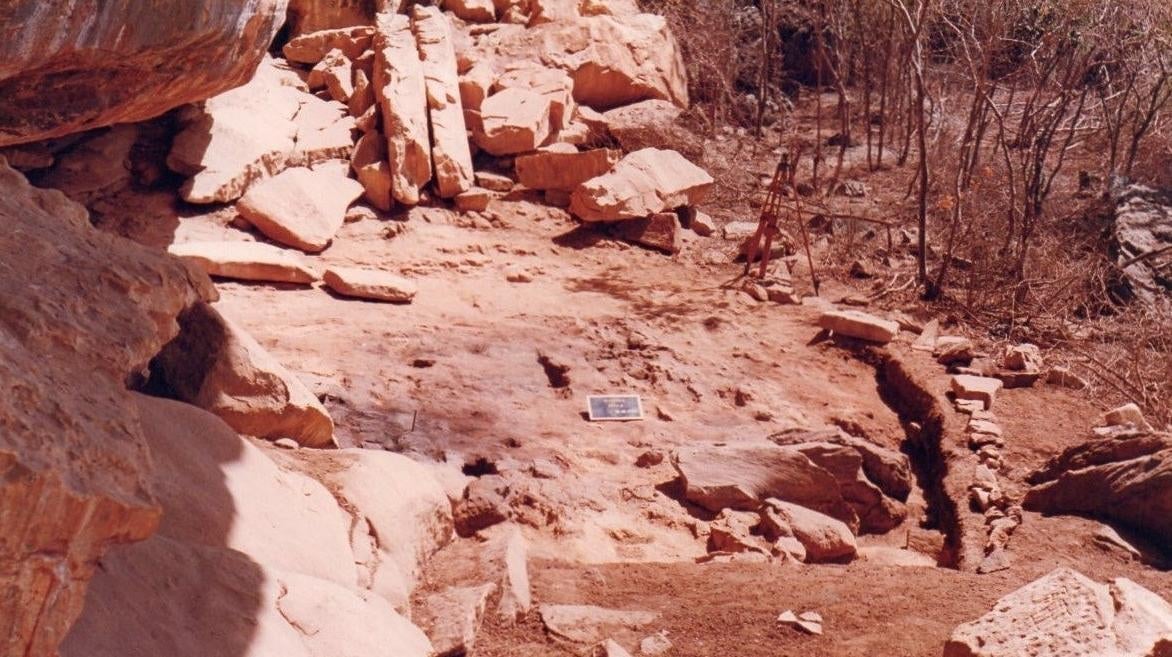

The oxygen-deprived environment created by the red mangrove peat has remarkably preserved wooden posts and other artifacts, offering a unique glimpse into the past. Excavated items, including building posts, ceramic fragments, notched wood, a ceramic spinning whorl, a possible fishing weight, a model boat, and a fragment of a human-shaped ocarina, were carefully stored underwater to prevent decay. The team employed specialized techniques, such as flotation devices and flags marking points of interest, to minimize disturbance to the delicate underwater site.

Salt Production and Trade within the Maya Civilization

“The Late Classic Maya integrated salt production as a key economic activity, relying on trade for other essential goods,” McKillop noted. The evidence suggests that the salt workers at Ta’ab Nuk Na likely traded their surplus salt for necessities like corn and other food, as well as non-local pottery found at the site.

The sheer scale of salt production at Ta’ab Nuk Na points towards a robust regional trade network. Based on comparisons with modern salt works in Guatemala, the researchers estimate that 10 salt kitchens in the Paynes Creek area could have yielded up to 60 tons of salt during the four-month dry season. The exact number of Paynes Creek sites operating concurrently during the Late Classic period remains uncertain.

Future Research and Implications

Further excavations are planned at smaller sites near Ta’ab Nuk Na to gain a comprehensive understanding of the extent of salt production in the region. The discovery of a pottery paddle at one site hints at a potential location for briquetage manufacturing.

This research underscores the sophisticated nature of Maya society, highlighting their extensive trade routes and complex economic systems. The findings at Ta’ab Nuk Na not only reveal the scale of salt production in Belize but also suggest the significant role this valuable commodity played in the intricate web of trade connecting Maya communities across Mesoamerica.

https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2022.106

https://www.sci.news/archaeology/maya-salt-money-09479.html

https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Plants-and-Fungi/Red-Mangrove