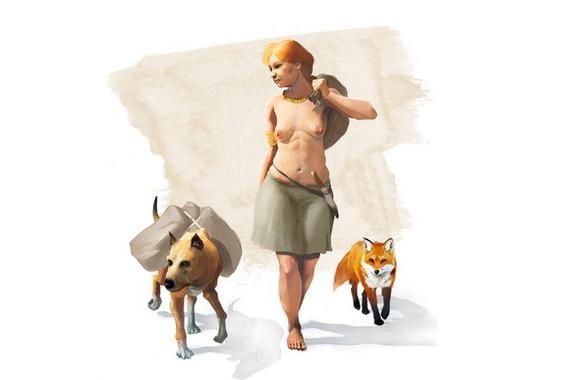

For decades, the narrative surrounding foxes and early humans depicted a simple predator-prey relationship. Recent archaeological discoveries, however, challenge this assumption, suggesting a far more complex interaction, potentially including domestication or, at the very least, a tolerated presence within human settlements. This article delves into the latest scientific findings, exploring the evolving understanding of the relationship between foxes and our ancestors.

Foxes and Funerary Rites

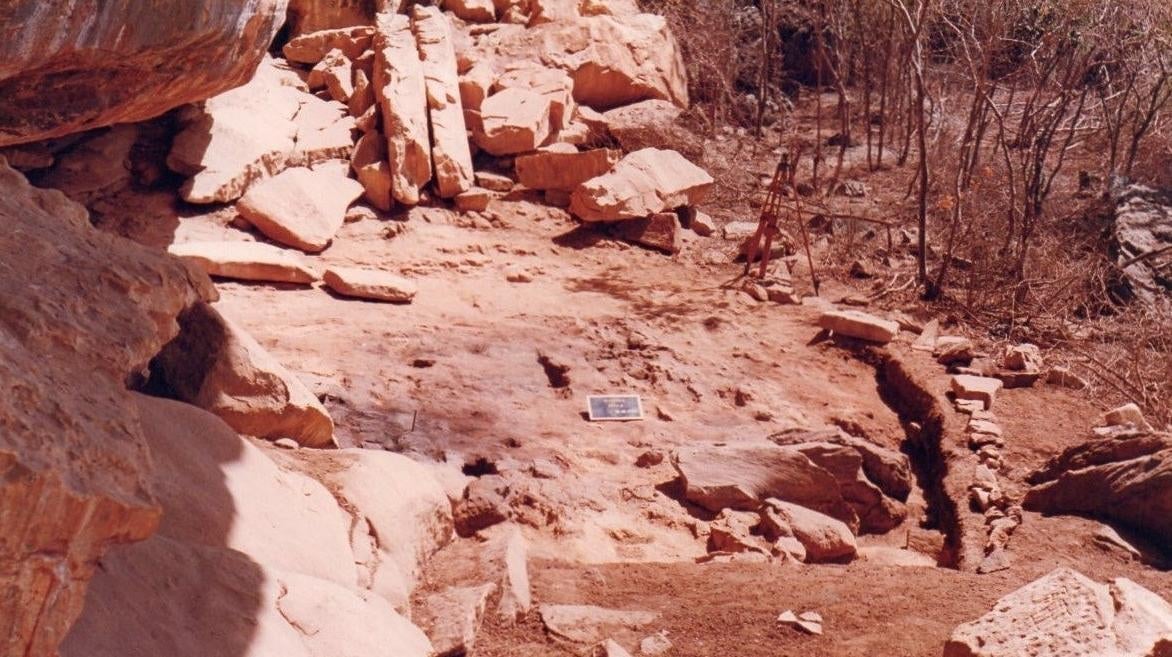

A recent study in Spain examined an agricultural burial site containing both human and fox remains. Researchers from various institutions analyzed bone collagen isotopes to reconstruct the diets of the deceased individuals. The site, Can Roqueta, dated back approximately 4,000 years and was primarily associated with domesticated animals like sheep and cattle, making the presence of fox bones a significant discovery. Lead researcher Aurora Grandal-d’Anglade, a senior lecturer at the University of A Coruña, highlighted the unexpected prevalence of fox remains, suggesting a special significance attached to these animals.

Illustration: J. A. PeñasIllustration: J. A. Peñas

Illustration: J. A. PeñasIllustration: J. A. Peñas

Isotopic analysis revealed that the foxes’ diets closely resembled those of some humans and dogs buried at the site, indicating a closer relationship than previously thought. Remarkably, one fox exhibited healed broken bones, suggesting human intervention and care. This particular fox also consumed a diet rich in vegetable protein, similar to that of young dogs at the site, further fueling speculation about human provisioning. While isotopic data cannot definitively confirm direct feeding, it adds another layer of intrigue to the human-fox dynamic. Grandal-d’Anglade emphasized the surprising nature of this finding, highlighting the potential for a more nuanced understanding of the relationship.

A History of Coexistence

Similar studies have uncovered intriguing parallels across different time periods and geographical locations. A study of a 15,000-year-old burial site in Germany and Switzerland revealed dietary differences between foxes living near human settlements and their wild counterparts. While the dietary distinction suggests a commensal relationship, with foxes likely scavenging human food scraps, it still points to a level of interaction beyond mere predation.

Further evidence comes from a 13,000-year-old burial in the Levant, where a human and a fox were interred together, both treated with red ochre, a practice not observed for other animal remains at the site. This unique burial, predating the appearance of domesticated dogs in the region, suggests the fox held a symbolic importance. The fact that the human and fox remains were kept together even after the grave was reopened and relocated underscores this special connection.

The Adaptable Fox

Foxes are known for their adaptability, as Kat Black, an adjunct biology instructor at Radford University, explains. Their opportunistic omnivorous diet allows them to thrive in diverse environments, capitalizing on anthropogenic food sources. This adaptability might have facilitated their integration into human settlements, whether as tolerated scavengers or intentional companions.

Documented instances of urban foxes in the 19th and 20th centuries, both in their native ranges and introduced areas, further illustrate this adaptability. However, coexisting with foxes has not always been harmonious. Black points out that foxes can become a nuisance due to behaviors like raiding garbage bins and gardens, leading to conflicts with human residents. Concerns about disease transmission also contribute to negative perceptions.

Despite these challenges, there are historical accounts of foxes being tamed and kept as pets, particularly in Finland, where urban foxes are common. One such example involved a fox captured in the Turku city barracks in 1921, which was subsequently kept as a pet. These historical anecdotes offer glimpses into the potential for closer human-fox relationships.

Rethinking Archaeological Interpretations

The emerging evidence suggests the need to revisit existing archaeological data with a fresh perspective. Grandal-d’Anglade argues that many fox remains may have been misclassified as hunting remnants, overlooking the possibility of closer human-fox interactions. She advocates for a more open-minded approach, considering various forms of evidence, such as diet and burial practices, to fully understand the complexities of these ancient relationships. By reevaluating existing archaeological sites, we may uncover further evidence of these intriguing connections.

Conclusion

The relationship between foxes and early humans appears to be far more nuanced than previously thought. While definitive proof of widespread domestication remains elusive, the accumulating evidence suggests a range of interactions, from commensalism to potential companionship. By combining archaeological findings with insights into fox behavior and adaptability, we can gain a richer understanding of the complex history between humans and these resourceful creatures. Further research and open-minded interpretations of existing data are crucial to unraveling the full story of this intriguing interspecies relationship.