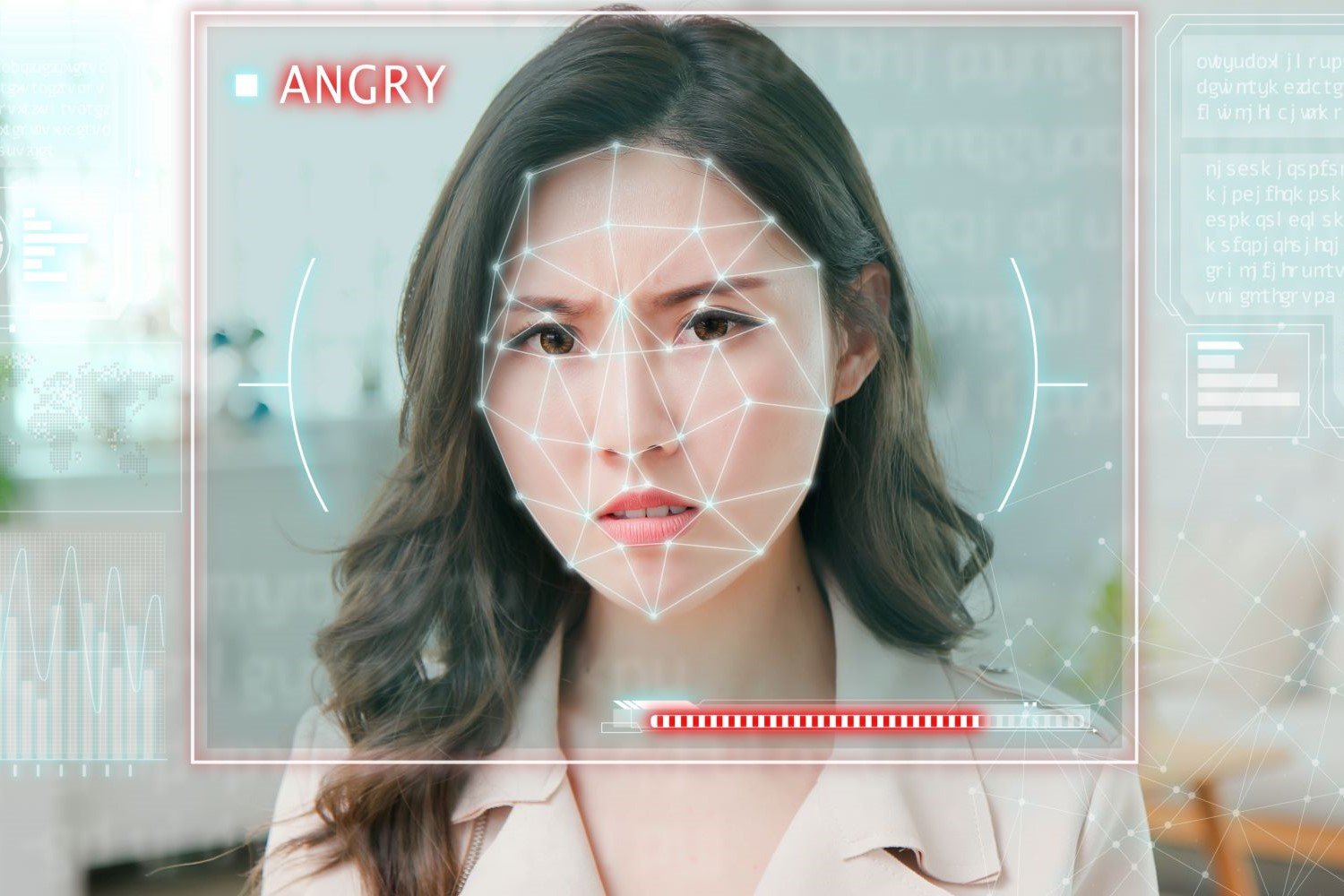

The idea of judging a person’s character and potential based on their facial features is an old and discredited one, reminiscent of 18th-century phrenology. However, a recent study by economics professors has reignited this controversial concept, using AI to analyze facial features and predict career outcomes.

This study, conducted by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, Indiana University, and Yale University, used AI to analyze LinkedIn profile pictures of 96,000 MBA graduates. The algorithm purportedly assessed personality traits based on the Big Five personality model (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism). These AI-generated personality scores were then correlated with the prestige of the graduates’ MBA programs and their estimated post-graduation incomes.

The researchers claim their analysis shows a correlation between “desirable” personality traits, as determined by their algorithm, and career success, including attending higher-ranked MBA programs and earning higher incomes. For example, men in the top 20% of “desirable” personalities supposedly attended MBA programs ranked 7.3% higher and had estimated incomes 8.4% higher than those in the bottom 20%. These effects were reduced when controlling for factors like race, age, and perceived attractiveness, all inferred by the algorithm.

A critical flaw in this study is the lack of independent verification of the AI-generated personality scores. The researchers did not administer actual personality tests to the individuals whose photos were analyzed, relying solely on the algorithm’s assessment. This raises serious questions about the accuracy and validity of the findings.

The authors acknowledge the potential for discrimination inherent in this type of analysis, stating that “personality extraction from faces represents statistical discrimination in its most fundamental form.” They advise against using this technique for labor market screening, yet their research seems to encourage further exploration into the application of such technologies.

Despite recognizing the ethical implications, the researchers proceeded with their study, highlighting the perceived importance of “non-cognitive skills” in career success. They suggest that using AI to analyze faces offers “new avenues for academic inquiry,” inviting further investigation into the ethical, practical, and strategic considerations of such technologies. This raises concerns about the responsible use of AI and the potential for perpetuating biased and discriminatory practices.

In conclusion, while the study suggests a correlation between facial features and career outcomes as interpreted by an AI, its methodology and lack of validation raise significant doubts. Furthermore, the authors’ acknowledgment of the discriminatory nature of such practices, coupled with their call for further research, underscores the complex ethical dilemmas surrounding the use of AI in this context.