The grueling working conditions endured by criminals and prisoners of war in ancient Egyptian gold mines were documented as early as the second century BCE. Greek historian and geographer Agatharchides described these laborers as “a great multitude,” all with bound feet, working relentlessly day and night. Recent archaeological discoveries at the Ghozza gold mine provide stark physical evidence supporting these historical accounts.

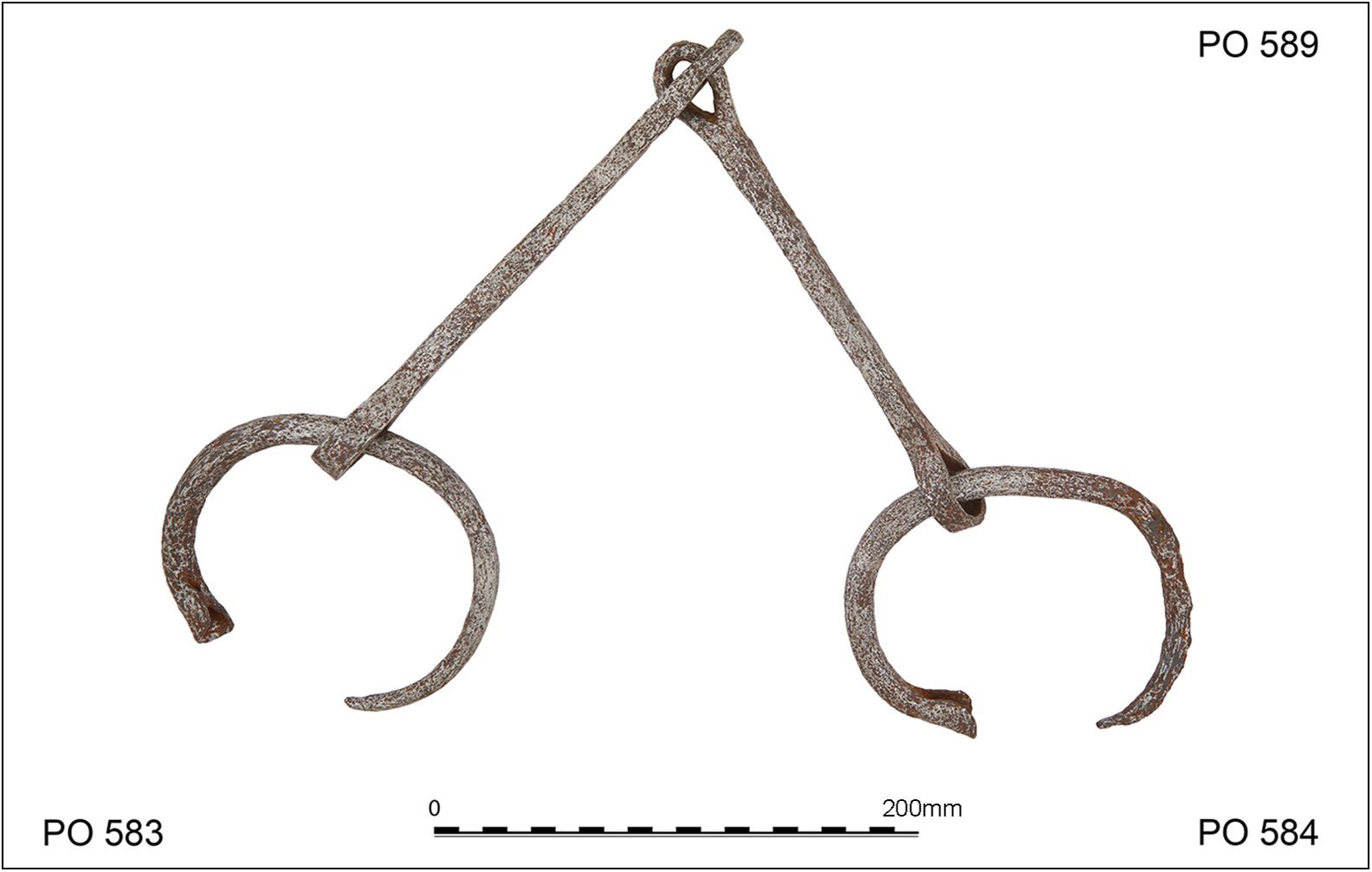

Iron shackles, designed to bind human ankles, were unearthed in Ghozza in January 2023. This finding offers a new perspective on labor practices at this site, which previously showed minimal signs of forced labor. Bérangère Redon, an archaeologist at the History and Sources of the Ancient Worlds laboratory in France, published these findings in a study in the journal Antiquity.

The Hellenistic Mining Boom and Ghozza’s Unique Context

While mining in ancient Egypt dates back to 1500 BCE, the Hellenistic period (332–30 BCE), under Ptolemaic rule, witnessed a surge in mining activity. The Ptolemies established nearly 40 new mines to fund military endeavors and construction projects. One such mine, Samut North, revealed evidence of miners housed in guarded dormitories. In contrast, Ghozza initially presented a different picture. Archaeological excavations uncovered residential areas, streets, baths, administrative buildings, and even wage records, suggesting a less restrictive environment.

The Discovery of Iron Shackles

The discovery of iron shackles in Ghozza challenges the initial perception of this mine. Found within a complex of buildings dedicated to storage, food preparation, and metalworking, these shackles represent some of the oldest examples discovered in the Mediterranean region. The presence of over a dozen foot-binding shackles points towards the existence of forced labor at the site.

Feet ShacklesThe iron shackles, likely fastened around workers’ ankles, offer a stark reminder of the harsh working conditions. © M. Kačičnik, Institut français d’archéologie orientale

Feet ShacklesThe iron shackles, likely fastened around workers’ ankles, offer a stark reminder of the harsh working conditions. © M. Kačičnik, Institut français d’archéologie orientale

Implications for Understanding Ancient Mining Practices

Redon’s study highlights the shackles’ design, specifically for human use. Their construction made removal without assistance impossible. Although allowing free hand movement, the weight and restrictive nature of the shackles would have made walking slow and arduous.

Parallels with Other Ancient Mines

These shackles bear a striking resemblance to those discovered in a Greek silver mine in the 1870s. This similarity, along with other evidence, suggests the adoption of Greek and Macedonian mining technologies, including methods for enforcing labor, in Egyptian mines during the Hellenistic period.

The Human Cost of Gold

The shackles serve as a poignant reminder of the human cost associated with ancient Egypt’s gold production. The wealth generated from these mines fueled the ambitions of the ruling elite, but it came at the expense of forced laborers subjected to harsh working conditions.

Forced Labor in a Broader Context

The use of forced labor was not exclusive to ancient Egypt; it was a common practice in many ancient civilizations. Further research at Ghozza, particularly the excavation of workers’ living quarters, could provide more insight into the lives and status of these laborers, revealing whether they were all forced into servitude or if a mix of free and forced labor existed.

Conclusion: Uncovering the Complexities of Ancient Labor

The discovery of iron shackles at the Ghozza gold mine adds a crucial dimension to our understanding of ancient Egyptian mining practices. While previous findings suggested a relatively free environment, the presence of these shackles underscores the complex realities of labor in this context. This discovery prompts further investigation into the diverse experiences of workers within the ancient mining industry, reminding us of the human toll behind the pursuit of precious resources.