A common house cat’s hunting prowess has led to the discovery of a novel virus in Florida, highlighting the potential for undiscovered pathogens lurking in our environment. Researchers identified a previously unknown jeilongvirus in a rodent captured by a domestic cat, raising questions about the virus’s potential to jump to humans.

This discovery underscores the importance of proactive surveillance for emerging viral threats in unexpected places. While the immediate risk to humans is thought to be low, further research is crucial to understand the virus’s behavior and potential for spillover events.

A Cat’s Curious Catch

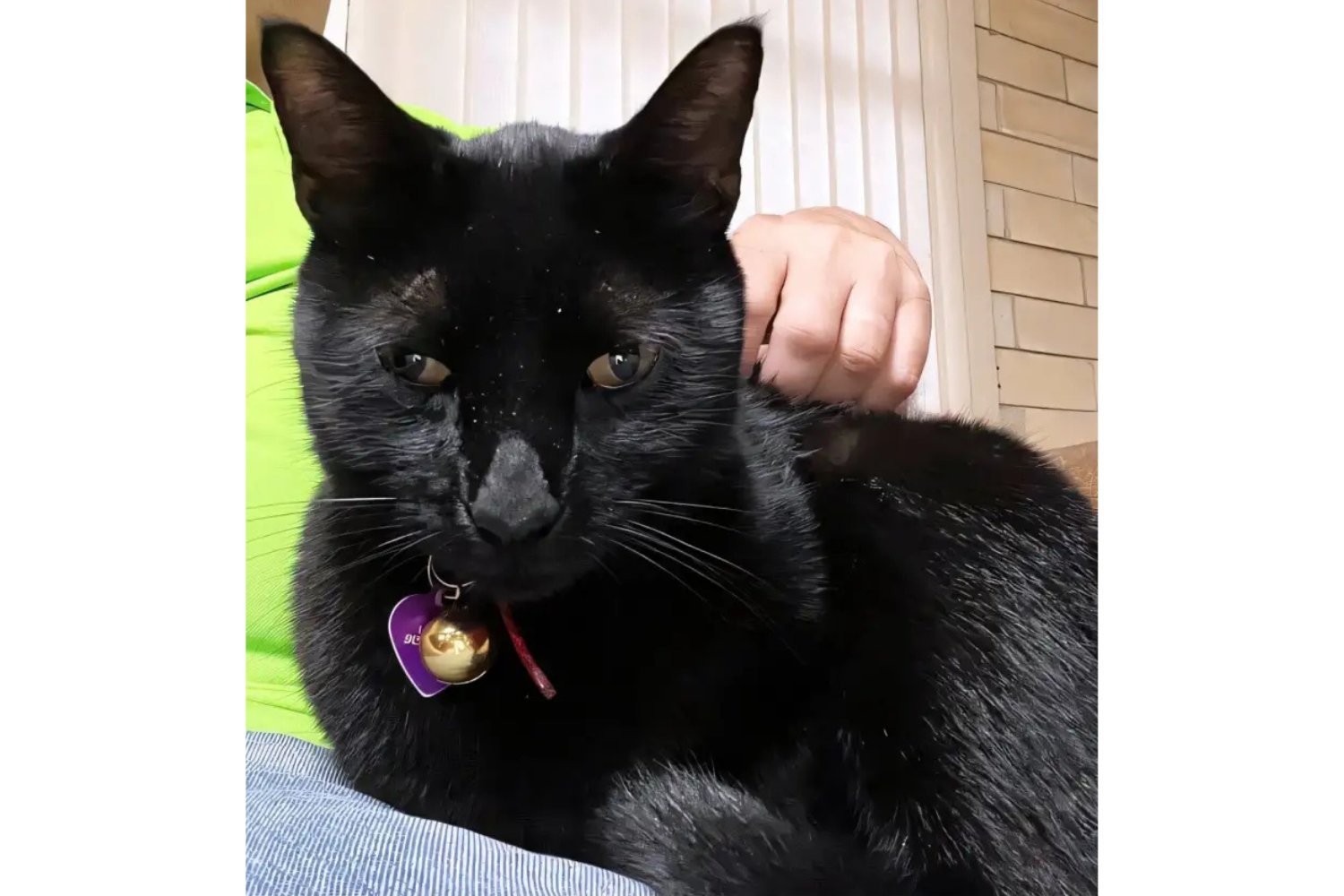

In May 2021, Pepper, a black cat belonging to University of Florida microbiologist John Lednicky, brought home a captured cotton mouse (Peromyscus gossypinus). Intrigued by the possibility of uncovering novel pathogens, Lednicky and his team decided to examine the rodent. Initially suspecting the presence of mule deerpox virus, the researchers were surprised to find a completely different virus – a jeilongvirus previously undocumented in the United States.

Pepper CatPepper the cat, whose hunting habits led to a scientific discovery. © John Lednicky

Pepper CatPepper the cat, whose hunting habits led to a scientific discovery. © John Lednicky

A New Jeilongvirus Emerges

Jeilongviruses belong to the Paramyxoviridae family, which includes viruses responsible for human diseases like measles and mumps. While other jeilongviruses have been identified globally, this new virus, dubbed Gainesville rodent jeilong virus 1 (GRJV1), is unique. Laboratory tests revealed GRJV1 can infect human and primate cells, suggesting a potential for cross-species transmission.

The study, published in Pathogens, details the discovery and characterization of GRJV1. “Millions of viruses are predicted to exist that have not yet been isolated,” Lednicky explained. “This one is of great interest because it appears to be a ‘generalist,’ able to affect cells from different types of animals including humans.”

Assessing the Risk

While GRJV1’s ability to infect human cells in a lab setting is concerning, the actual risk to human health is currently considered low. Direct contact with rodents, the primary hosts of jeilongviruses, is relatively infrequent in modern human populations. Furthermore, even known rodent-borne diseases like hantavirus only cause sporadic outbreaks in humans.

However, the possibility of undetected human infections cannot be ruled out. Many paramyxoviruses cause respiratory symptoms similar to the common cold, and routine diagnostic testing rarely screens for less common viruses like GRJV1. This raises the question of whether GRJV1 might already be circulating undetected in human populations.

Future Research and Funding Challenges

Further research is vital to understand GRJV1’s full potential. Scientists need to investigate its effects on rodent hosts and explore the possibility of past spillover events in humans. Lednicky plans to conduct animal studies and investigate the presence of GRJV1 antibodies in human populations. However, securing funding for such research remains a challenge.

“The problem we encounter is lack of funding,” Lednicky stated. “The NIH no longer funds many ‘surveillance’ studies. And when a new pathogen is found, funding agencies tend to fund work only for those which have caused outbreaks in humans.” He emphasizes the need for unrestricted private funding or dedicated government support to continue this crucial research, highlighting the high costs and specialized facilities required.

A Cat’s Instinctive Wisdom?

Interestingly, Pepper, the cat at the center of this discovery, seems to exhibit an instinctive caution. He typically consumes only the front portion of his rodent prey, avoiding organs like the kidneys, spleen, and intestines, where many dangerous rodent-borne viruses reside. Whether this is driven by instinct or coincidence remains a mystery.

The discovery of GRJV1 serves as a potent reminder of the vast, unexplored world of viruses and the potential for unexpected discoveries in our own backyards. Continued research and proactive surveillance are essential to prepare for and mitigate future threats from emerging pathogens.