Tesla recently issued a “recall” affecting nearly 2 million vehicles in the U.S. and Canada due to issues with its “Autosteer” feature, often mistakenly called “Autopilot.” This prompts a critical discussion: what constitutes a recall in the age of software-defined vehicles?

The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) describes the issue as an increased crash risk if drivers using Autosteer fail to maintain control and intervene when necessary. While driver error is a factor, the vehicle’s safety systems should mitigate such risks. The solution? An over-the-air (OTA) software update. This raises the question: is a software update truly a “recall”?

A Tesla Model 3 at a Supercharger station.A Tesla Model 3 charging at a Supercharger station. The recent software update highlights the evolving relationship between software and vehicle safety.

A Tesla Model 3 at a Supercharger station.A Tesla Model 3 charging at a Supercharger station. The recent software update highlights the evolving relationship between software and vehicle safety.

Traditionally, a recall involves physically taking your car to a service center for repairs. This contrasts sharply with a software update, which happens seamlessly in the background. Technically, both fall under the umbrella of “safety-related defects,” as defined by the NHTSA. This broad definition encompasses any flaw in a vehicle’s performance, construction, components, or materials. While this breadth is necessary given a vehicle’s complexity, it highlights the need for more precise terminology.

The distinction between a software and hardware recall becomes crucial when considering the remedies. A faulty batch of tires requires physical replacement, while faulty code requires a software patch. The impact on the owner’s experience is vastly different.

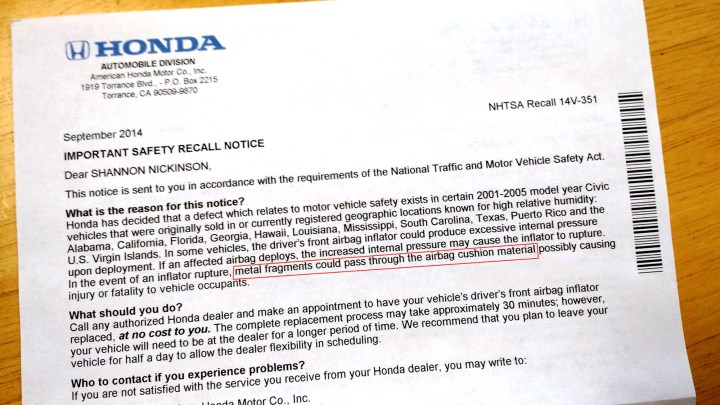

A letter from Honda announcing a recall for faulty airbgs.A recall notice for faulty airbags, requiring physical replacement. This contrasts with the ease of software updates.

A letter from Honda announcing a recall for faulty airbgs.A recall notice for faulty airbags, requiring physical replacement. This contrasts with the ease of software updates.

Compare this with the Takata airbag recall, affecting 67 million airbags. This recall necessitated physical replacement, requiring owners to take their vehicles to dealerships. Both scenarios address critical safety concerns, but the methods of resolution are fundamentally different. While notification and manufacturer responsibility remain crucial in both cases, the term “recall” loses its impact when no physical action is required from the owner.

Tesla’s voluntary recall involves an OTA software update to implement additional controls and alerts, encouraging driver responsibility while using Autosteer. This update is being deployed currently. While it may not prevent all driver misuse, it represents a proactive step towards enhancing safety.

Modern vehicles are increasingly reliant on software. This shift necessitates clearer language to differentiate between software and hardware recalls. This distinction is essential for effective communication and to ensure that critical safety information isn’t overlooked. As language evolves, so too must our understanding of terms like “recall” in the automotive world.