Colossal Biosciences, a company focused on groundbreaking genetic engineering to effectively resurrect extinct species, announced significant progress in its ambitious project to de-extinct the thylacine, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger. This carnivorous marsupial was officially declared extinct in 1936 due to relentless hunting and habitat destruction. In a recent press release, Colossal revealed its reconstructed thylacine genome is now approximately 99.9% complete, with only 45 remaining gaps that they aim to close through further sequencing in the coming months.

Recovering RNA and Building a Genome

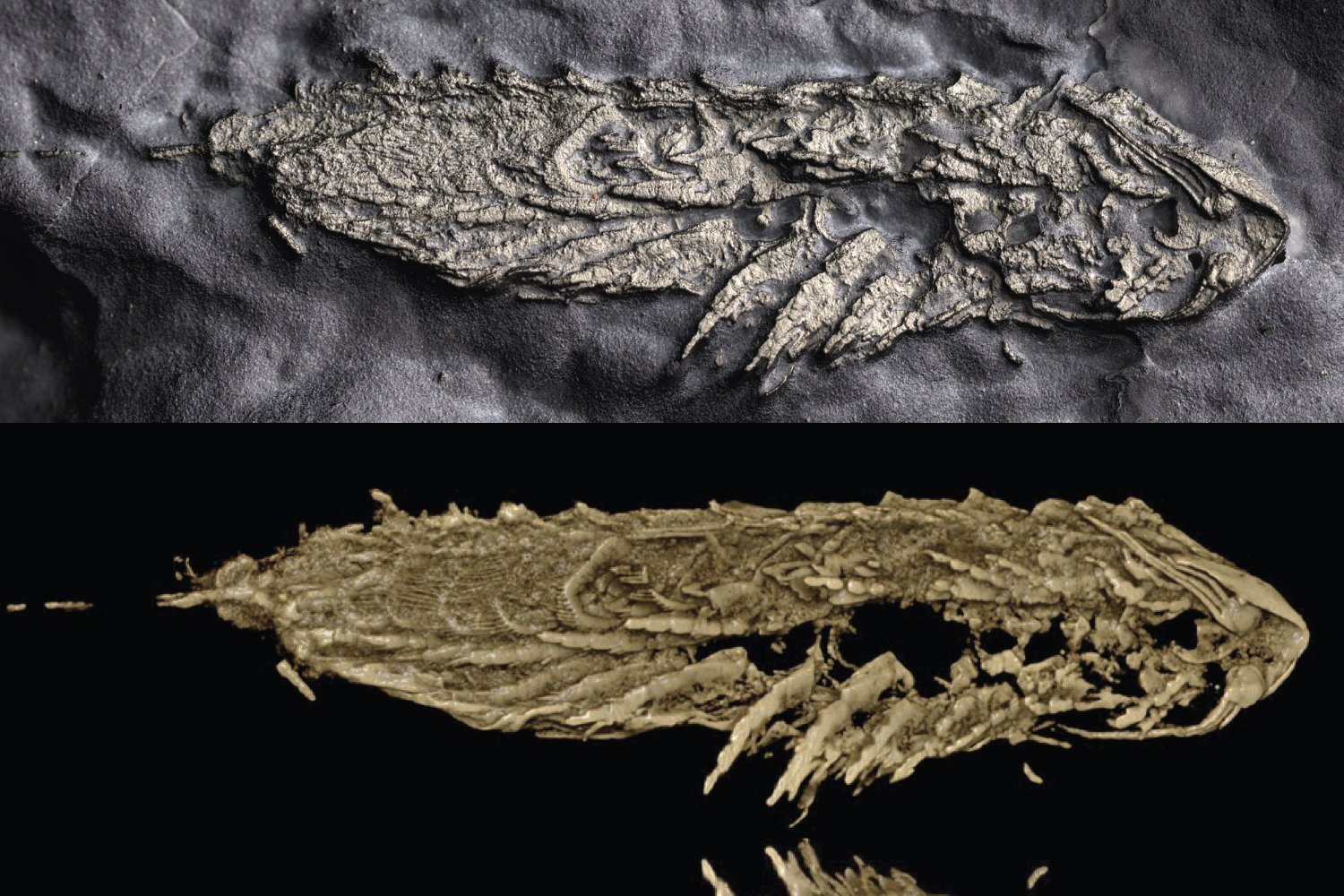

Last year, a separate research team achieved a scientific first by successfully recovering RNA from a thylacine specimen, a feat recognized by the maagx.com Science Fair. Building upon this achievement, Colossal announced it has isolated long strands of RNA from a 110-year-old thylacine specimen preserved in ethanol. This milestone contributes significantly to their ongoing de-extinction efforts. Colossal first declared its intention to “de-extinct” the thylacine in 2022. Since no living thylacines remain, the process involves creating a proxy species—essentially a replacement that will resemble the original thylacine and occupy a similar ecological niche. Colossal also plans to reintroduce these proxy species to their original habitats, or the closest modern equivalent.

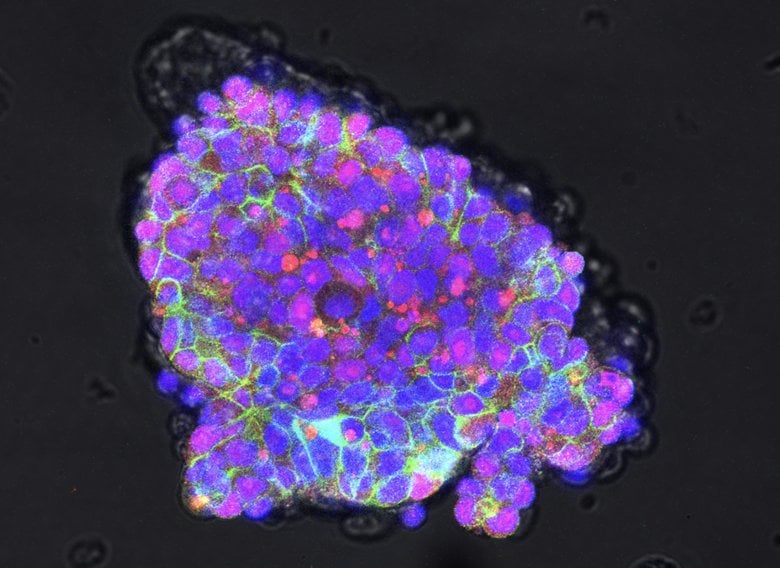

A colony of fat-tailed dunnart stem cells.A colony of fat-tailed dunnart stem cells. Image: Colossal Biosciences

A colony of fat-tailed dunnart stem cells.A colony of fat-tailed dunnart stem cells. Image: Colossal Biosciences

The Challenges of Genetic Restoration

Often referred to as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian/marsupial wolf, the thylacine is neither feline nor canine but the sole member of its genus, Thylacinus cynocephalus. To de-extinct the animal, Colossal plans to genetically modify the cells of the fat-tailed dunnart, the thylacine’s closest living relative, to create the nearest possible approximation of the original species. While the reconstructed genome is nearly complete, some genetic information remains irretrievable. This was highlighted in a previous maagx.com article discussing the de-extinction potential of the extinct Christmas Island rat. A researcher involved in that project, and now a member of Colossal’s advisory board, expressed reservations about the prioritization of such projects, suggesting resources could be better directed towards conserving existing species. Ethical concerns also persist, questioning whether a genetically engineered proxy truly represents a de-extinction of the thylacine, which was tragically driven to extinction by human actions.

The Mammoth in the Room and Other Projects

Earlier this year, maagx.com interviewed Beth Shapiro, Colossal’s chief science officer, to discuss the company’s plans, timelines, and the ethical considerations surrounding de-extinction. Colossal had previously announced the successful engineering of elephant stem cells, a key step toward their goal of creating a cold-resistant, hairy Asian elephant—a modern-day equivalent of the woolly mammoth. In the recent press release, Colossal co-founder and CEO Ben Lamm emphasized the team’s commitment to accelerating the science required to make extinction a thing of the past.

Improving the Resilience of Extant Species

Beyond de-extinction efforts, Colossal is also working on the genomes of living species, such as the northern quoll. The company reported enhancing the quoll’s resistance to toxins from the invasive cane toad, introduced to Australia in 1935 to control pests. Unfortunately, the cane toad poses a threat to native species, including the northern quoll. Andrew Pask, a member of Colossal’s Scientific Advisory Board and researcher at the University of Melbourne’s Thylacine Integrated Genomic Restoration Research Laboratory (TIGRR Lab), highlighted the significance of this achievement, stating that a single base change in a 3-billion base pair genome can dramatically increase the quoll’s resistance to cane toad toxins.

The Future of Gene Editing and Conservation

Colossal’s diverse projects demonstrate the rapid advancements in gene editing technology. As Ross MacPhee, a mammalogist at the American Museum of Natural History, predicted last year, “manufactured organisms” will likely become a reality within the next decade. However, the long-term ecological consequences of these interventions remain uncertain. Whether Colossal can learn from past environmental manipulations, such as the introduction of the cane toad, will ultimately determine the success and ethical implications of their ambitious endeavors, particularly in the delicate ecosystems of Tasmania.