The Ptychodus, a fossil shark first identified 190 years ago, has long remained an enigma in the paleontological world. Recent discoveries, however, are finally painting a clearer picture of this ancient fish. A new study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B presents an exceptionally well-preserved Ptychodus fossil, complete from nose to tail, offering unprecedented insights into its anatomy and evolutionary history.

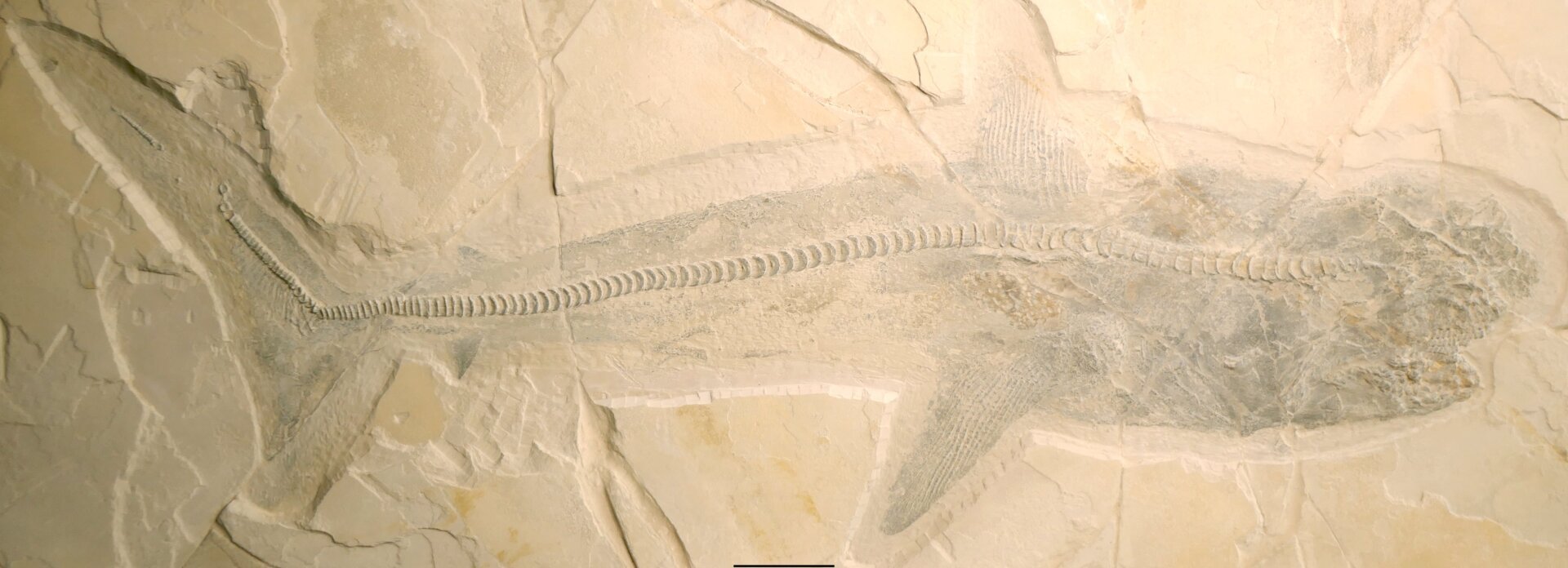

Researchers analyzed six near-complete Ptychodus specimens unearthed in Vallecillo, Mexico, over the past decade. These remarkably preserved fossils showcase not only the shark’s skeletal structure but also the outline of its body. This level of preservation has allowed scientists to glean new information about the shark’s anatomy and its position within the shark family tree.

“This study offers critical information on the evolutionary relationships and paleoecology of Ptychodus,” said Romain Vullo, lead author of the study and a paleontologist at the University of Rennes in France. “Previously, this Cretaceous shark was primarily known from isolated teeth, sets of teeth, and a few skeletal fragments like vertebrae.”

An artist’s impression of Ptychodus as a shell-chomping mackerel shark.An artist’s rendering depicts Ptychodus, an ancient shark, feeding on ammonites in the open ocean.

An artist’s impression of Ptychodus as a shell-chomping mackerel shark.An artist’s rendering depicts Ptychodus, an ancient shark, feeding on ammonites in the open ocean.

The complete specimens from Mexico reveal that Ptychodus was a fast-swimming open-ocean shark, similar in shape to the modern porbeagle. Its specialized grinding teeth suggest a diet primarily consisting of ammonites and sea turtles, according to Vullo. This finding adds another layer to our understanding of this ancient predator’s ecological niche.

Vullo, who also led the 2021 study describing the unusual Cretaceous shark Aquilolamna milarcae found in the same region of Mexico, classified Ptychodus as a lamniform, or mackerel shark. The study proposes that competition with mosasaurs, a group of extinct marine reptiles, may have contributed to the Ptychodus’s extinction.

However, Tyler Greenfield, a paleontologist at the University of Wyoming unaffiliated with the new study, offers an alternative perspective. He suggests that Ptychodus may belong to a different shark category altogether.

“Lamniform sharks exhibit specific patterns in their tooth size and shape, the structure of their jaws, and the cartilage within their vertebrae, which Ptychodus lacks,” Greenfield explained. He argues that the study’s authors overlooked these features, relying instead on cranial and jaw characteristics that are not exclusive to lamniforms to classify Ptychodus.

Close-up view of a Ptychodus fossil, highlighting its unique tooth structure and jaw features.A detailed view of a Ptychodus fossil showcases the distinctive features of its teeth and jaws, central to the debate surrounding its classification.

Close-up view of a Ptychodus fossil, highlighting its unique tooth structure and jaw features.A detailed view of a Ptychodus fossil showcases the distinctive features of its teeth and jaws, central to the debate surrounding its classification.

Greenfield proposes that Ptychodus, along with similar ancient sharks like Squalicorax and Ptychocorax, should be classified under a separate order, Anacoraciformes, or crow sharks. He points to similarities between these sharks and suggests that their shell-crushing teeth likely evolved independently of the lamniforms.

“My hypothesis aims to create a more accurate understanding of the relationships and diversity of prehistoric sharks,” Greenfield stated. This alternative classification adds another layer of complexity to the Ptychodus story.

While such well-preserved fossils might be expected to resolve questions about the shark’s lineage, they have instead sparked further debate. Regardless of the final classification, the existence of these exceptional specimens provides invaluable material for paleontologists to refine our knowledge of this intriguing ancient predator.

The ongoing research surrounding Ptychodus highlights the dynamic nature of scientific discovery. These remarkable fossils offer a glimpse into a prehistoric world and fuel ongoing investigations into the complex history of life on Earth.