Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the devastating bubonic plague, underwent a subtle genetic evolution that may have allowed infected rodents to survive longer, according to groundbreaking new research. This adaptation could have played a crucial role in prolonging two of history’s most significant plague pandemics, including the infamous Black Death, by altering the dynamics of Yersinia pestis evolution and its spread.

Researchers from the Institut Pasteur in France and McMaster University in Canada analyzed hundreds of ancient Y. pestis DNA samples, focusing on a gene known as “pla.” Their findings, published on May 29 in the journal Science, revealed a reduction in the number of ‘pla’ gene repetitions within the Y. pestis genome during the later phases of both the first and second major plague pandemics. The scientific team posits that these depletions in the ‘pla’ gene ultimately contributed to the extended duration of these devastating outbreaks.

The ‘Pla’ Gene: A Double-Edged Sword in Plague Virulence

The ‘pla’ gene is a significant factor in the virulence of Y. pestis. According to a statement from the Institut Pasteur, this gene, which can appear multiple times in the bacterium’s genome, enables Y. pestis to effectively infect the lymph nodes before disseminating throughout the host’s body. This process typically leads to rapid septicemia (blood poisoning) and swift death for the victim. Consequently, a reduction in ‘pla’ gene copies in Y. pestis strains from the major historical pandemics likely rendered the bacterium less acutely lethal, the researchers propose. This newly identified aspect of Yersinia pestis evolution offers deeper insight into the prolonged persistence of these diseases.

Ancient DNA Unveils a Pandemic-Prolonging Adaptation

The first major plague pandemic, often called the Plague of Justinian, swept through the Mediterranean basin in the sixth century, claiming tens of millions of lives over approximately two centuries. The second pandemic began with the Black Death in 1347, which exterminated an estimated 30% to 50% of Europe’s population within a mere six years. However, this was not the end; similar to the first pandemic, this plague continued to resurface for centuries, its impact lasting over 500 years. The study’s analysis of ancient DNA samples showed a decrease in ‘pla’ gene repetitions in Y. pestis strains circulating during the later stages of these extensive pandemics. This suggests an adaptive change where slightly less aggressive strains became more common over time.

Experimental Insights: How Milder Strains Spread Further

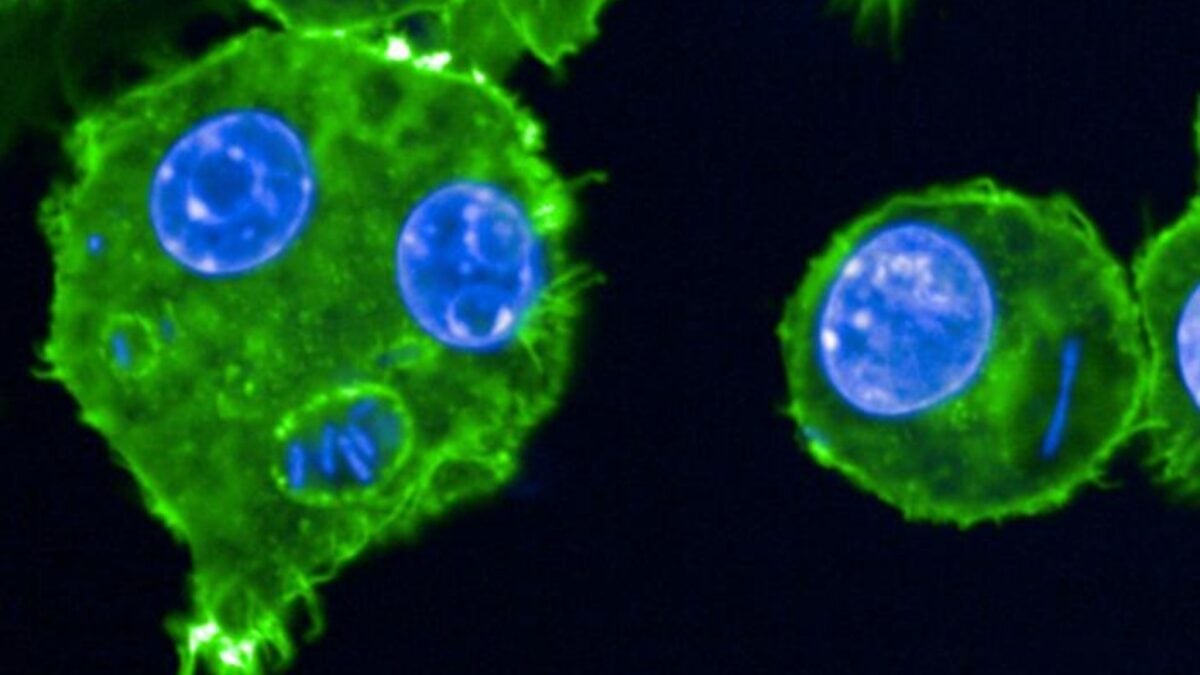

To investigate their hypothesis, the research team infected laboratory mice with three preserved Y. pestis strains from the third major plague pandemic, which also exhibited fewer ‘pla’ gene repetitions. “These three samples enabled us to analyze the biological impact of these pla gene deletions,” explained co-author Javier Pizarro-Cerdá, director of the Yersinia Research Unit at the Institut Pasteur, in the institutional statement.

The mouse model experiments revealed that the ‘pla’ gene depletion led to a 20% reduction in host mortality. Crucially, infected rodents survived significantly longer. Based on these results, the researchers concluded that rats infected with these less virulent, ‘pla’-depleted Y. pestis strains likely acted as more effective disease vectors. With extended lifespans, these rodents had more opportunities to spread the plague bacterium to fleas, which then transmitted it to humans. Rodents, particularly rats, were pivotal in spreading the bubonic plague. Humans typically contract the disease from infected flea bites, and fleas usually acquire it by feeding on infected rodents. Therefore, longer survival times for these infected animals would have amplified the chances for fleas to become infected and subsequently bite humans. [internal_links]

Understanding Pathogen Evolution: Lessons from the Past

“Ours is one of the first research studies to directly examine changes in an ancient pathogen, one we still see today, in an attempt to understand what drives the virulence, persistence, and eventual extinction of pandemics,” stated co-lead author Hendrik Poinar, director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Centre. This research not only illuminates the evolutionary past of Y. pestis and the catastrophic pandemics it triggered but also serves as a valuable model for understanding how deadly diseases emerge, adapt, and disseminate.

Today, the bubonic plague is classified as a rare disease, although isolated cases continue to appear in regions such as western North America, Africa, Asia, and South America, as noted by the Cleveland Clinic. The insights gained from studying the historical Yersinia pestis evolution, particularly the role of the ‘pla’ gene, are vital for comprehending the complex interplay between pathogen genetics and pandemic dynamics.

In conclusion, this compelling research indicates that a subtle genetic adaptation in Yersinia pestis – specifically, a reduction in ‘pla’ gene copies – likely made the bacterium less immediately fatal. This, in turn, allowed infected rodent hosts to live longer, enhancing their capacity to spread the disease and thereby contributing to the remarkable and devastating persistence of historical plague pandemics. Understanding such evolutionary mechanisms in pathogens is crucial for predicting and potentially mitigating the impact of future infectious disease outbreaks.

References

- Paphitou, A., Kozlov, M., Carmona, D., et al. (2024). Pla Pangenome and Deletions in Ancient Yersinia pestis Strains. Science. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adt3880

- Keller, M., Spyrou, M.A., Scheib, C.L., et al. (2019). Ancient Yersinia pestis genomes from across Western Europe reveal early diversification during the First Pandemic (541–750). PNAS, 116(25), 12363-12372. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1903797116

- Institut Pasteur. (2024). Plague bacillus became less virulent, prolonging the duration of the two major pandemics. https://www.pasteur.fr/en/press-area/press-documents/plague-bacillus-became-less-virulent-prolonging-duration-two-major-pandemics

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Bubonic Plague. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21590-bubonic-plague