The Genyornis newtoni, an extinct bird twice the weight of an ostrich, roamed Australia during the Ice Age. Recent fossil discoveries are shedding new light on this giant avian, revealing its aquatic adaptations and intriguing evolutionary history. Weighing in at approximately 500 pounds (230 kilograms), Genyornis was five times heavier than the formidable southern cassowary. A remarkable trove of remains, including a nearly foot-long skull, unearthed in South Australia’s Lake Callabonna in 2019, has provided crucial insights into this prehistoric giant.

This significant find follows the discovery of the only other known Genyornis skull in 1913, which was unfortunately heavily damaged. The new fossils, coupled with advanced technology, have enabled researchers to draw more detailed conclusions about the life and extinction of this fascinating creature. Their research is published in Historical Biology.

Lake Callabonna, described as a “megafauna necropolis” by paleontologist Jacob Blokland of Flinders University and co-author of the study, has been a known fossil site since the late 1800s, though its significance likely predates recorded history through Indigenous knowledge. Early interpretations classified Genyornis as a “struthious bird,” akin to cassowaries and emus, influencing subsequent reconstructions.

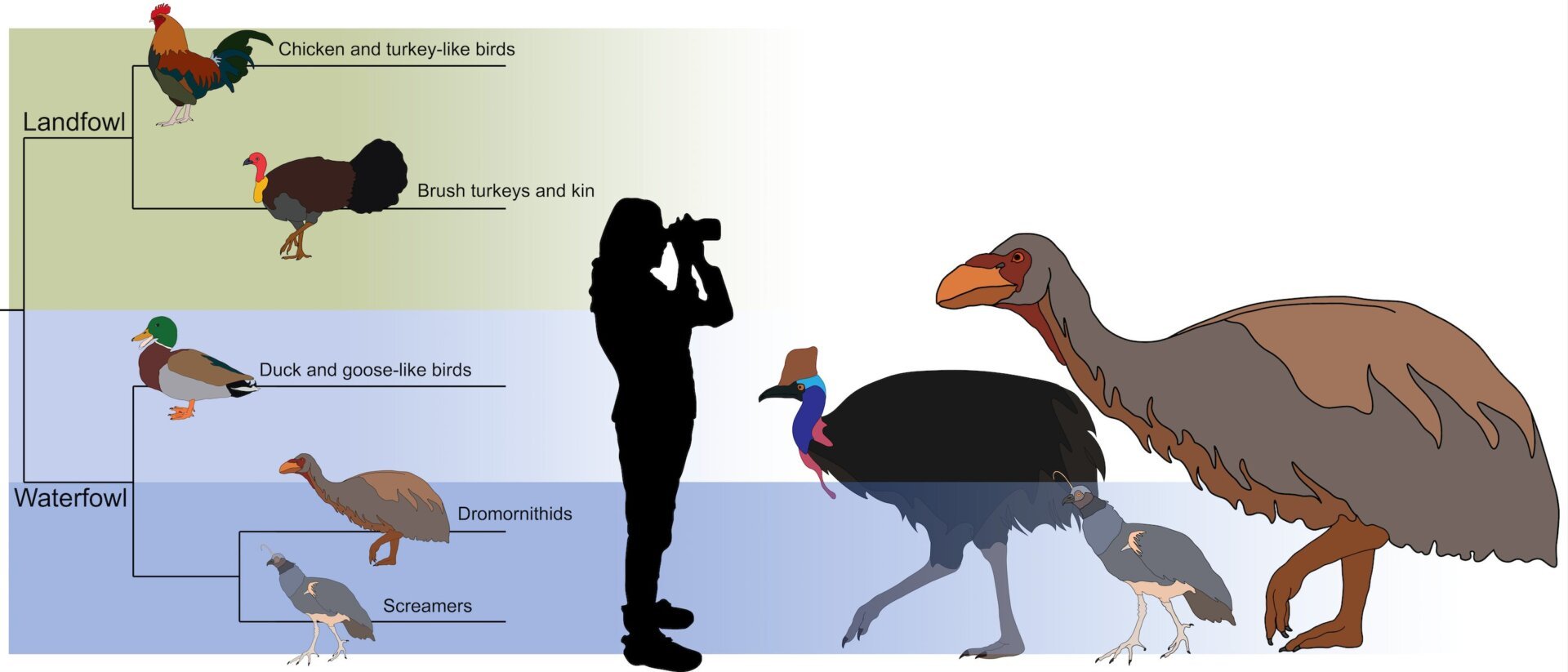

A graphic showing the placement of Genyornis among other birds and a size comparison with the cassowary and screamers.Genyornis size comparison with other birds, including the cassowary and screamers.

A graphic showing the placement of Genyornis among other birds and a size comparison with the cassowary and screamers.Genyornis size comparison with other birds, including the cassowary and screamers.

However, this recent study challenges previous assumptions. The bird’s upper jaw, tall like a parrot’s but shaped like a goose’s, earned it the nickname “giga-goose.” The skull reveals a large braincase and a casque, a bony protrusion on the top of its head. While its size invites comparisons to large terrestrial birds, the research suggests a closer morphological resemblance to modern waterfowl, particularly the South American screamers.

The new skull material points to a semi-aquatic lifestyle, with features suggesting the bird submerged its head in water to forage. This adaptation suggests a diet of soft aquatic plants or new plant shoots. In contrast, its hindlimbs show adaptations for traversing hard ground, indicating potential movement between lakes, perhaps supplementing its diet with fruits and other terrestrial food sources.

Genyornis’s extinction around 45,000 years ago places it contemporaneously with anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals (though not in Australia). While no evidence exists of direct interaction between humans and Genyornis, they coexisted in the same region.

A reconstruction of Genyornis’ skull.Reconstructed skull of Genyornis, highlighting its unique features.

A reconstruction of Genyornis’ skull.Reconstructed skull of Genyornis, highlighting its unique features.

The cause of Genyornis’s extinction remains unclear, likely due to a complex interplay of factors. Lead author Phoebe McInerney, a paleontologist at Flinders University, suggests the bird’s aquatic adaptations indicate a dependence on semi-aquatic environments. During Genyornis’s time, the inland lakes of South Australia were undergoing drought periods, gradually transitioning to their current arid state. This environmental shift likely contributed to the bird’s local extinction.

While the exact reasons for its disappearance are uncertain, the new research significantly clarifies Genyornis’s morphology and ecological niche. Further fossil discoveries may unlock more details about this intriguing giant waterfowl of the Ice Age.