Alzheimer’s disease research may be at a turning point. New clinical trial data suggests it’s possible to delay symptoms in individuals genetically predisposed to develop early-onset Alzheimer’s. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine explored the potential of gantenerumab, an experimental anti-amyloid drug, in individuals with inherited Alzheimer’s. A subset of patients treated the longest showed a 50% reduction in their risk of developing anticipated symptoms. While requiring further investigation, these preliminary findings offer cautious optimism for the future of Alzheimer’s treatment.

“These results offer genuine hope that treating Alzheimer’s pathology in its preclinical stages can effectively slow or prevent disease onset,” commented Thomas M. Wisniewski, director of the Center for Cognitive Neurology at NYU Langone Health, who was not involved in the research.

Targeting Amyloid Plaques: The Gantenerumab Approach

Gantenerumab is one of many antibodies designed to target beta-amyloid, a protein implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. In affected individuals, misfolded amyloid beta accumulates in the brain, forming plaques that contribute to the disease’s progression. The theory is that drugs like gantenerumab can disrupt and prevent plaque formation, potentially halting or slowing Alzheimer’s.

Past Setbacks and Recent Advances

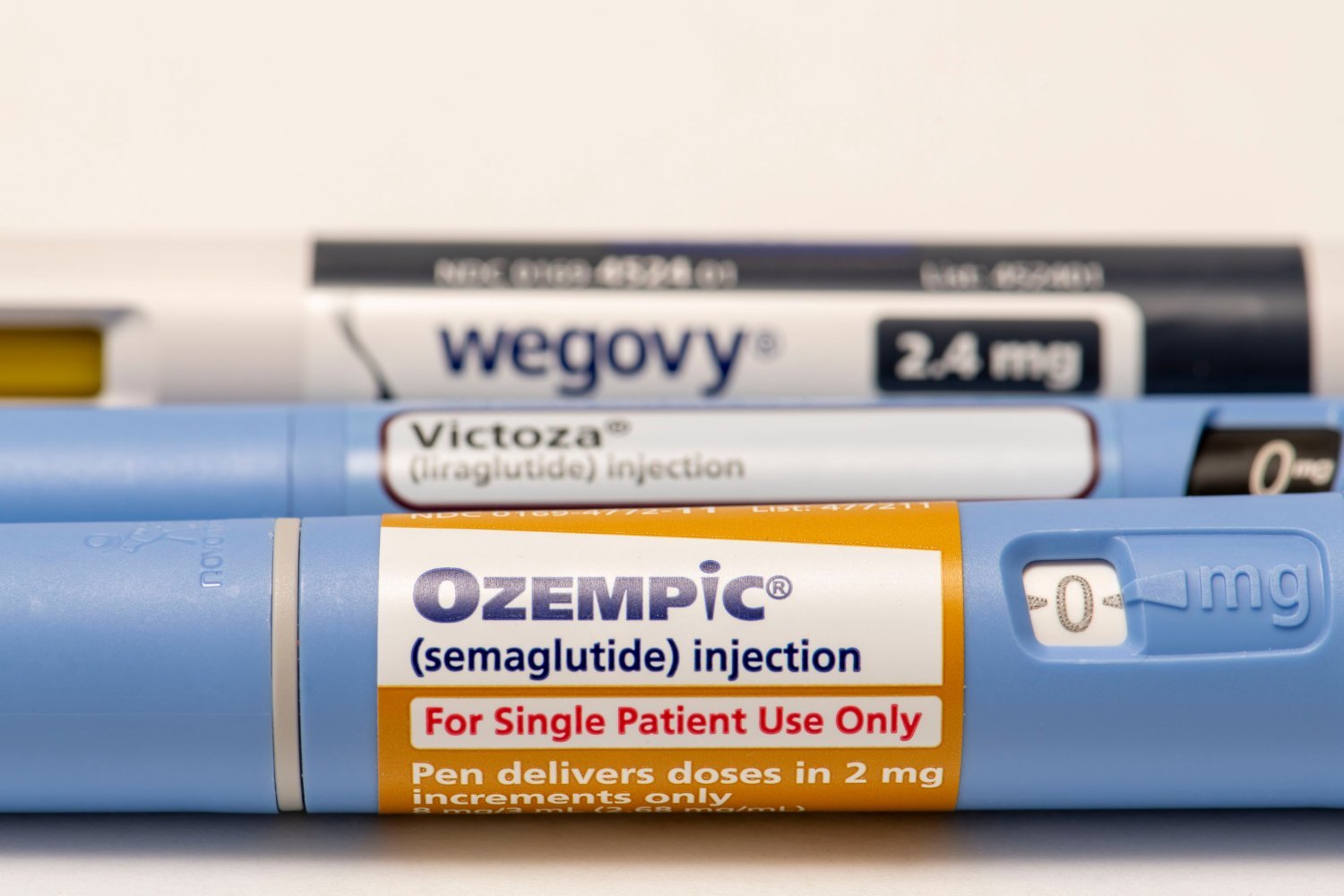

The path for anti-amyloid drugs has been challenging. Many initially promising treatments failed in larger trials involving patients already experiencing symptoms, including gantenerumab itself. Roche halted its development in late 2022 after two Phase III trials proved unsuccessful. However, more recent anti-amyloid drugs like lecanemab and donanemab have demonstrated modest but significant effects in slowing Alzheimer’s progression, earning FDA approval. Researchers, including those at WashU Medicine, believe that earlier intervention, before symptom onset, could enhance the effectiveness of anti-amyloid treatment.

The Gantenerumab Prevention Trial

Beginning in 2012, prevention trials were initiated, testing anti-amyloid agents in individuals with dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s – a genetic condition virtually guaranteeing dementia onset between the ages of 30 and 50. While most trials yielded limited success, the gantenerumab trial showed promise. Initial results in 2020 indicated a reduction in amyloid levels, but it was too early to assess symptom delay. Subsequently, an extension study provided open-label gantenerumab to all participants, including those previously receiving placebo or another drug.

Promising New Data and Important Considerations

The latest results, published in The Lancet Neurology, have generated excitement. “Every participant in this study was destined to develop Alzheimer’s, and some haven’t yet,” stated senior author Randall J. Bateman, a neurology professor at WashU Medicine. “We don’t know how long they’ll remain symptom-free—it could be years or even decades.”

However, important caveats exist. The findings only suggest a potential preventative benefit. While the drug may have reduced cognitive decline risk in the larger asymptomatic group, this reduction wasn’t statistically significant, possibly due to the small sample size (73 patients). In a subset of 22 asymptomatic patients treated the longest (around eight years), the risk reduction was approximately 50%. The trial’s premature termination due to Roche’s decision and participant dropout further complicate interpretation.

While generally safe and tolerable, about a third of participants experienced amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIAs), indicating brain swelling or bleeding. ARIAs are a known side effect, often unnoticed. Two patients experienced severe ARIAs, leading to temporary treatment discontinuation and subsequent recovery. No life-threatening events or deaths were reported.

Looking Ahead: Ongoing Research and Hope for the Future

This study doesn’t definitively prove the long-term efficacy of anti-amyloid drugs in preventing Alzheimer’s. However, given the inevitability of early-onset Alzheimer’s in this population, the results are encouraging. Combined with the approval of lecanemab and donanemab for classic Alzheimer’s, the findings suggest a tangible therapeutic avenue.

“We already know from lecanemab and donanemab data that anti-amyloid antibodies can slow the progression of common, sporadic Alzheimer’s,” noted Sam Gandy, associate director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mount Sinai, who wasn’t involved in the research. “This study demonstrates a similar phenomenon with gantenerumab in genetic early-onset Alzheimer’s.”

Ongoing prevention trials for both early-onset and classic Alzheimer’s, including those by WashU’s Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network-Trials Unit, are exploring approved and experimental anti-amyloid drugs, potentially revealing even greater protective benefits. Many participants in the gantenerumab extension study have transitioned to lecanemab, and the resulting data awaits analysis.

While early, these developments offer genuine hope in the fight against this currently incurable disease.