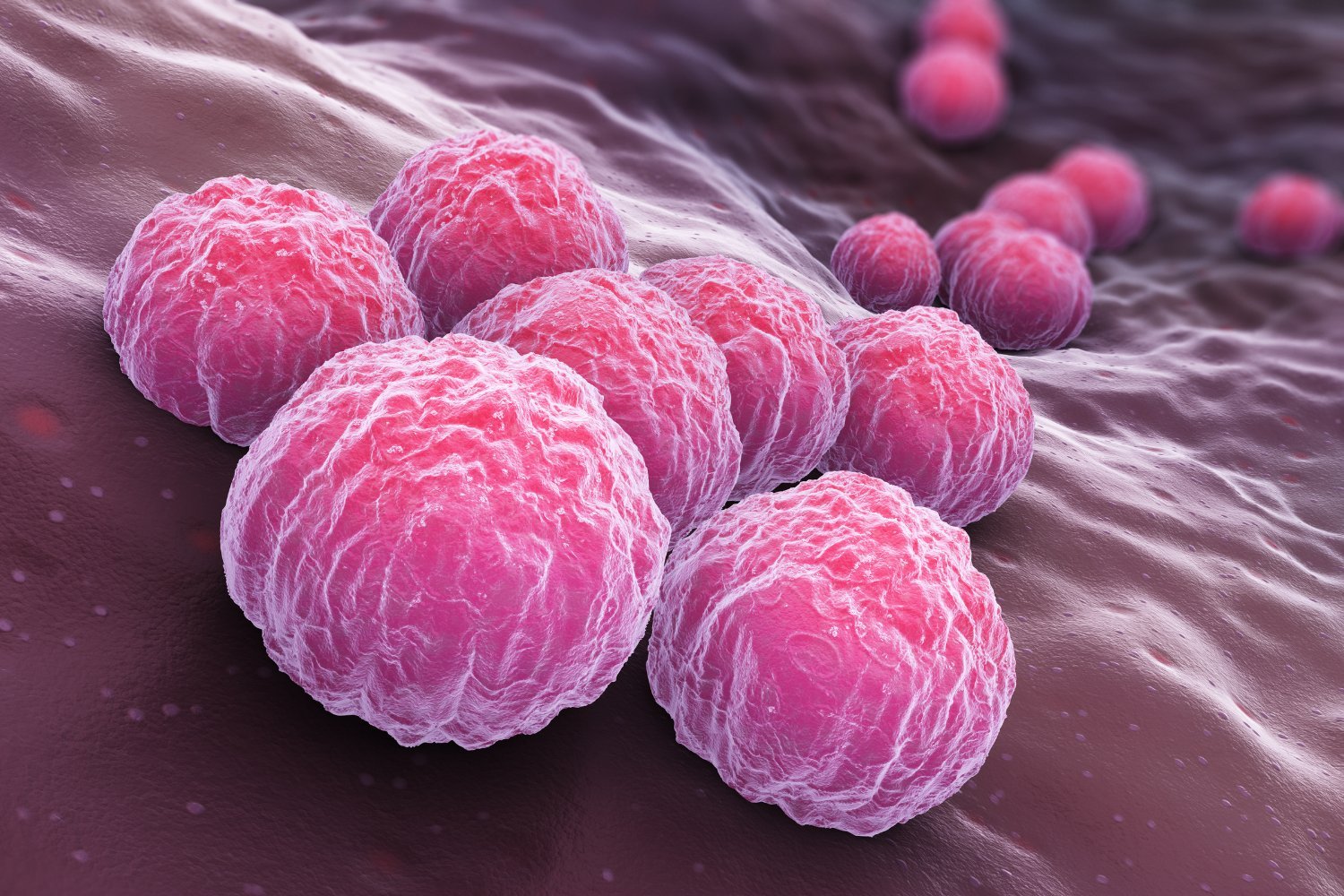

Fasting has become a popular dietary trend, with many touting its potential health benefits. However, new research suggests that fasting’s effects on the body, specifically on intestinal stem cells, may be more complex than previously thought. While fasting can promote the healing of these crucial cells, it might also increase their susceptibility to cancerous transformations. This research, conducted on mice, highlights the need for further investigation to optimize fasting practices like intermittent fasting for human health.

A team of scientists at MIT recently published their findings in the journal Nature. Building upon their previous research, which demonstrated fasting’s ability to enhance intestinal stem cell regeneration, this study delves into the underlying mechanisms of this process.

The researchers divided mice into three groups: a control group with regular feeding, a group fasted for 24 hours, and a group fasted for 24 hours followed by unrestricted feeding for the next 24 hours. Surprisingly, they observed that stem cell regeneration was suppressed during the fasting period but significantly increased during the refeeding phase.

“The key finding of our study is that refeeding after fasting is a distinct physiological state,” explained the study researchers, Omer Yilmaz, Shinya Imada, and Saleh Khawaled. “Post-fasting refeeding enhances the ability of intestinal stem cells to repair the intestine, for example, after injury.”

This accelerated regeneration, while beneficial for healing, could potentially have a downside. When the researchers introduced cancer-linked mutations into the stem cells during the refeeding phase, the cells exhibited a greater propensity to form precancerous polyps compared to the fasting phase. This raises concerns about the potential long-term effects of fasting on cancer risk.

It’s important to emphasize that the complexities of human physiology make it difficult to directly extrapolate these findings from mice to humans. Further research is crucial to determine whether similar effects occur in human intestinal stem cells.

“Biological pathways are intricate and interconnected,” the researchers cautioned. “Therefore, rigorous studies are necessary to evaluate the impact of any dietary intervention on the human body.”

This research provides valuable insights into the mechanisms of fasting. The researchers discovered that fasting mice produced elevated levels of polyamines, organic compounds that play a crucial role in cell growth, division, and differentiation. They plan to investigate whether polyamine supplements can replicate the effects of fasting in future studies, potentially harnessing the benefits without the associated risks.

“Intermittent fasting is a widely practiced diet with reported benefits for various health conditions,” the researchers stated. “However, a deeper understanding of the distinct phases of fasting – the fasting period itself and the post-fast refeeding period – is essential. This will enable us to design dietary interventions that maximize regenerative benefits while minimizing potential risks, such as an increased risk of cancer.”

In conclusion, this study reveals the multifaceted nature of fasting’s impact on intestinal stem cells, highlighting both its potential for healing and its possible link to increased cancer risk. Further research is needed to translate these findings to humans and optimize fasting strategies for improved health outcomes. The exploration of polyamine supplementation offers a promising avenue for harnessing the benefits of fasting while mitigating potential risks.