Life expectancy, a key indicator of overall health, saw remarkable growth throughout the 20th century. This upward trend, fueled by advancements in medicine and public health, led many to believe that human lifespan could continue to extend indefinitely. However, recent research suggests this progress is slowing, indicating we may be approaching a natural limit to our longevity.

A new study published in Nature Aging examines mortality data from countries boasting the highest life expectancies, including Japan, South Korea, Australia, France, and Spain, alongside the United States for comparison. Focusing on the period between 1990 and 2019, researchers observed a deceleration in the rate of life expectancy increase, particularly after 2010. This slowdown occurred despite accelerated advancements in medical technology, suggesting that simply treating individual age-related diseases may not be enough to significantly extend lifespan further.

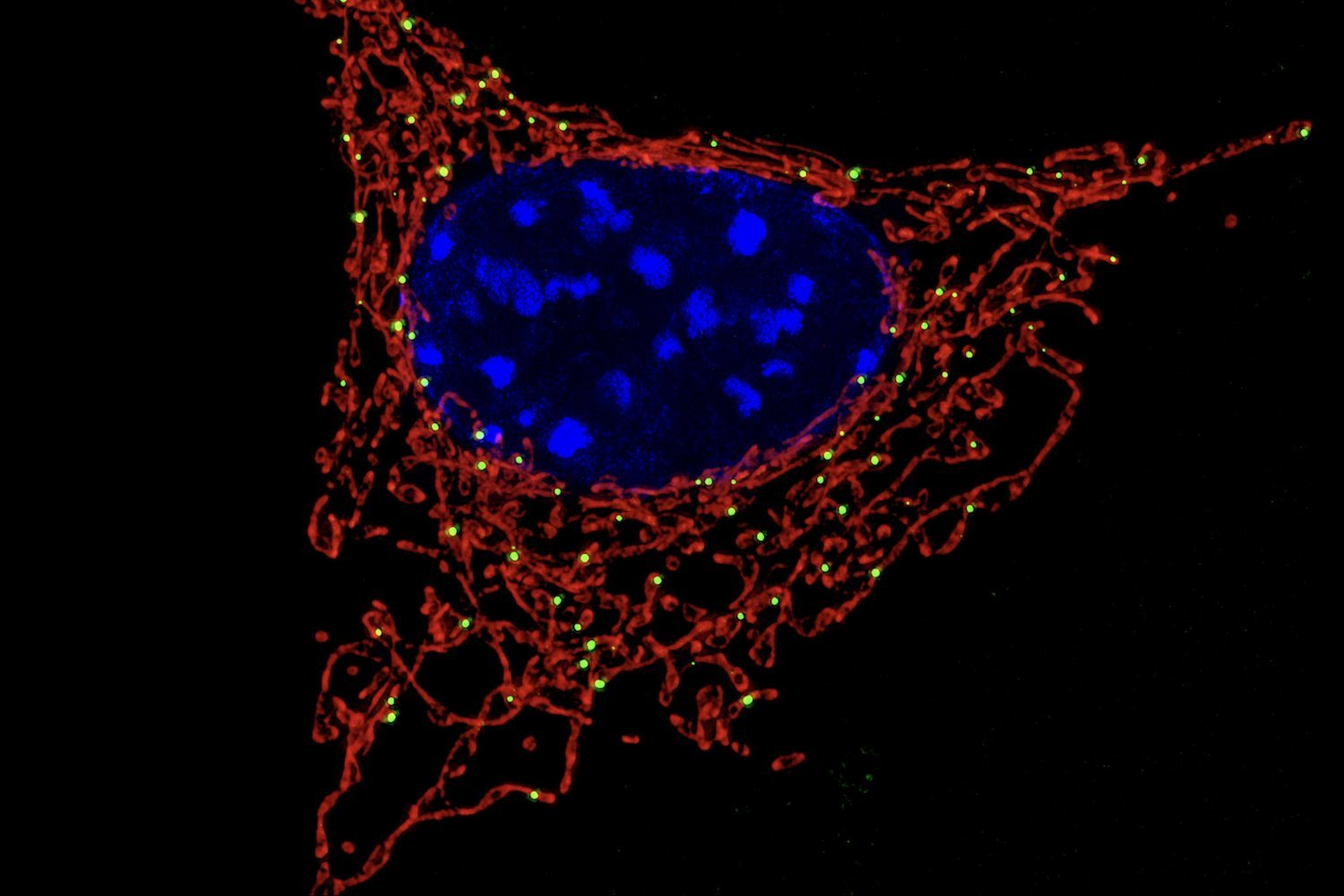

The study’s lead author, Stuart Jay Olshansky, a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, predicted this plateau decades ago. His team’s findings now confirm his earlier predictions, highlighting the potential limitations of a disease-specific approach to extending life. While medical advancements have undoubtedly extended our lives, allowing many to live well into their 70s, 80s, and beyond, this “manufactured time” often comes at the cost of chronic age-related illnesses like heart disease, cancer, stroke, and Alzheimer’s. Olshansky argues we are essentially playing “Whack-a-Mole” with these diseases, treating them individually rather than addressing the underlying process of aging itself.

The research indicates that even in the countries with the highest life expectancies, relatively few individuals born in 2019 are projected to reach the age of 100. The study estimates that approximately 12.8% of women and 4.4% of men in these countries are likely to become centenarians. In the U.S., these figures are even lower, with only 3.1% of women and 1.3% of men born in 2019 expected to reach a century.

Despite these findings, Olshansky remains optimistic about the future of longevity research. He points to the burgeoning field of geroscience, which focuses on understanding and manipulating the aging process itself. While he acknowledges promising developments and increased investment in this area, he cautions against the hype surrounding anti-aging treatments, emphasizing the importance of focusing on healthspan – the number of years lived in good health – rather than solely on lifespan extension.

Olshansky believes that significant breakthroughs in geroscience are on the horizon. He stresses that the true value of these advancements lies not in simply adding years to our lives, but in improving the quality of those years. He cautions against exaggerated claims of radical life extension and emphasizes the need for realistic expectations. The ultimate goal, he argues, should be to ensure that the time we do have is lived in the best possible health.

While the elusive “fountain of youth” may remain a fantasy, the pursuit of healthy aging offers a more attainable and impactful objective. Focusing on improving healthspan, rather than solely extending lifespan, may ultimately lead to a longer, healthier, and more fulfilling life for all.