The iconic pyramids of Giza, along with 30 other Egyptian pyramids, appear to be strategically placed along a now-vanished branch of the Nile River, according to a recent study published in Communications Earth & Environment. This discovery sheds light on the logistical marvel of ancient Egyptian engineering and offers valuable insights into the civilization’s resourcefulness.

This cluster of pyramids, including renowned structures like the Bent Pyramid and the Step Pyramid of Djoser, stretches across a narrow desert strip west of the current Nile. Constructed over a millennium, starting approximately 4,700 years ago, their location has long puzzled researchers. The study reveals a 40-mile (64-kilometer) long extinct Nile branch, dubbed “Ahramat” (Arabic for “pyramids”), which once flowed through this now-arid region. This lost waterway provides a compelling explanation for the seemingly isolated placement of these monumental structures, far from the main course of the Nile, the lifeblood of ancient Egypt and the longest river in the world.

Uncovering the Lost River: Ahramat

The research team, led by archaeologist Eman Ghoneim from the University of North Carolina Wilmington, employed a combination of satellite imagery, geophysical surveys, and sediment cores extracted from the Western Desert Plateau to identify the long-buried Ahramat branch. The discovery not only clarifies the pyramids’ locations but also offers crucial information for preserving Egyptian cultural heritage. As the authors note, understanding the location of this ancient waterway can help pinpoint potential ancient settlements and protect them from the encroachment of modern urbanization.

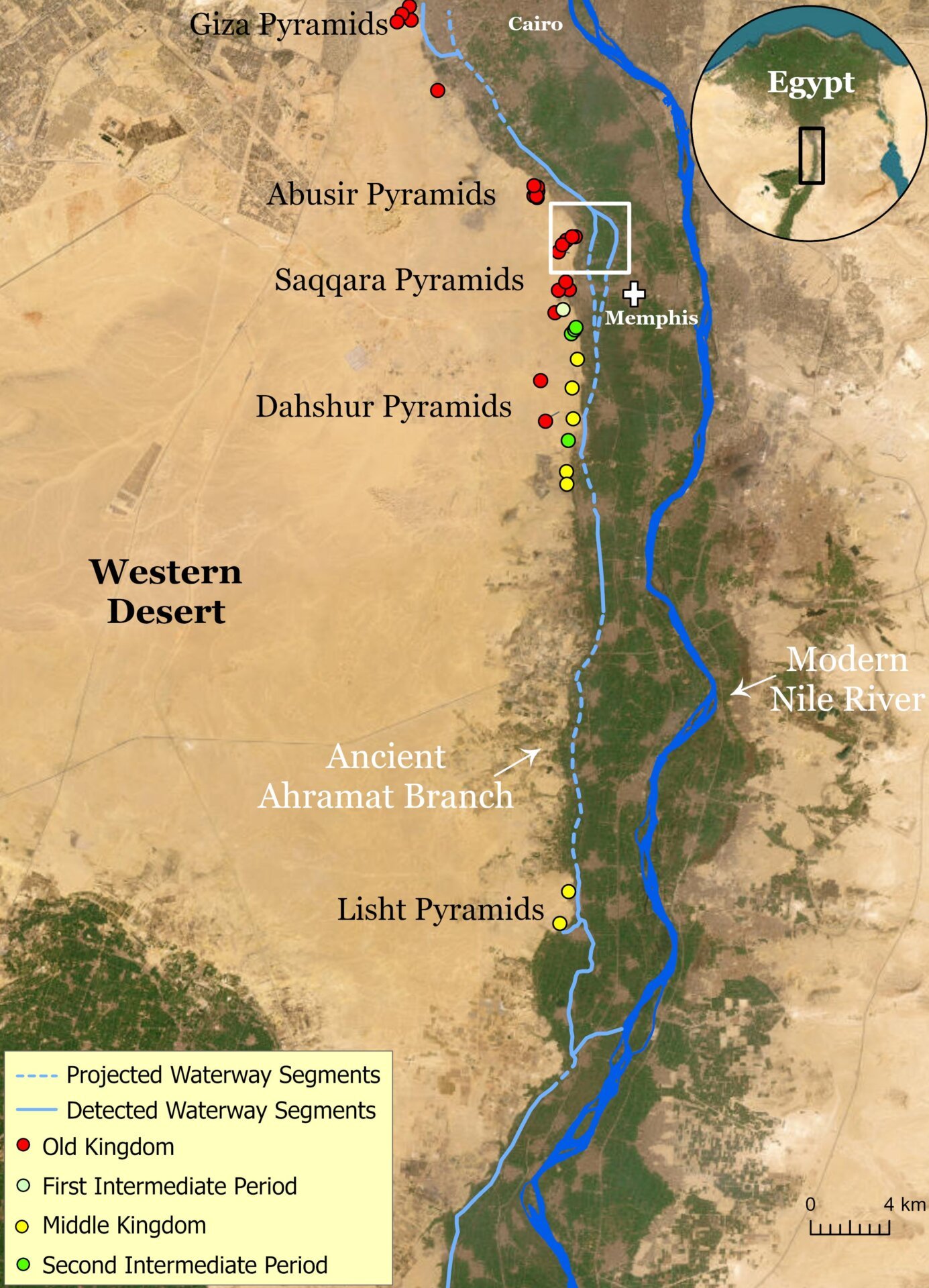

A map showing the placement of the ancient river branch.

A map showing the placement of the ancient river branch.

The Role of Ahramat in Pyramid Construction

Further investigation revealed causeways extending from many pyramids on the Western Desert Plateau towards the Ahramat branch. This strongly suggests the river’s vital role in transporting the massive quantities of building materials required for these colossal construction projects. The sheer scale of these undertakings continues to fascinate and inspire awe.

Hidden Inlets and the Giza Inlet

Sand-filled inlets, now invisible to conventional optical satellite imagery, once fed the Ahramat branch. However, radar and topographic data have revealed these hidden riverbeds, along with causeways leading to the pyramids of Pepi II and Merenre. Another arm of the river system, designated the “Giza Inlet,” was connected by causeways to the pyramids of Khafre, Menakure, and Kentkaus. This indicates the Ahramat branch remained active during the Old Kingdom’s fourth dynasty.

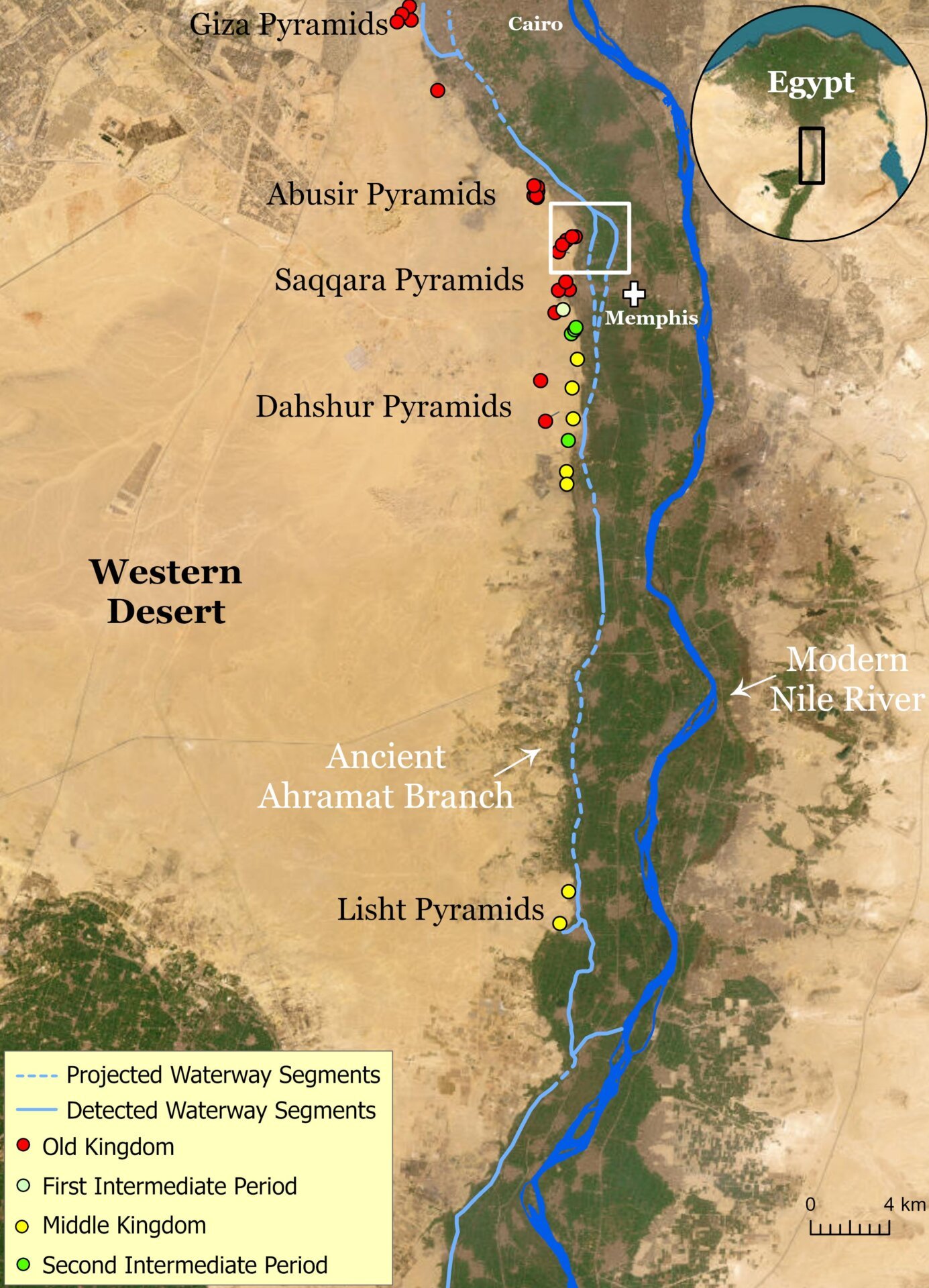

A graphic of Egypt's ancient waterways.

A graphic of Egypt's ancient waterways.

The Decline of Ahramat

The study suggests the Ahramat branch began its decline around 4,200 years ago. A significant drought likely exacerbated the accumulation of windblown sand, gradually filling the riverbed and eventually obscuring it, even from satellite view. Thanks to modern technology, including radar imagery and sediment coring, this vital ancient Egyptian resource has been brought back to light.

Conclusion

The discovery of the Ahramat river branch provides a significant piece of the puzzle in understanding the construction and logistics of the ancient Egyptian pyramids. It highlights the ingenuity and resourcefulness of this remarkable civilization, demonstrating their sophisticated understanding of their environment and their ability to harness its resources for monumental projects. This research also underscores the importance of continued archaeological investigation and the use of advanced technologies to uncover the secrets of the past.