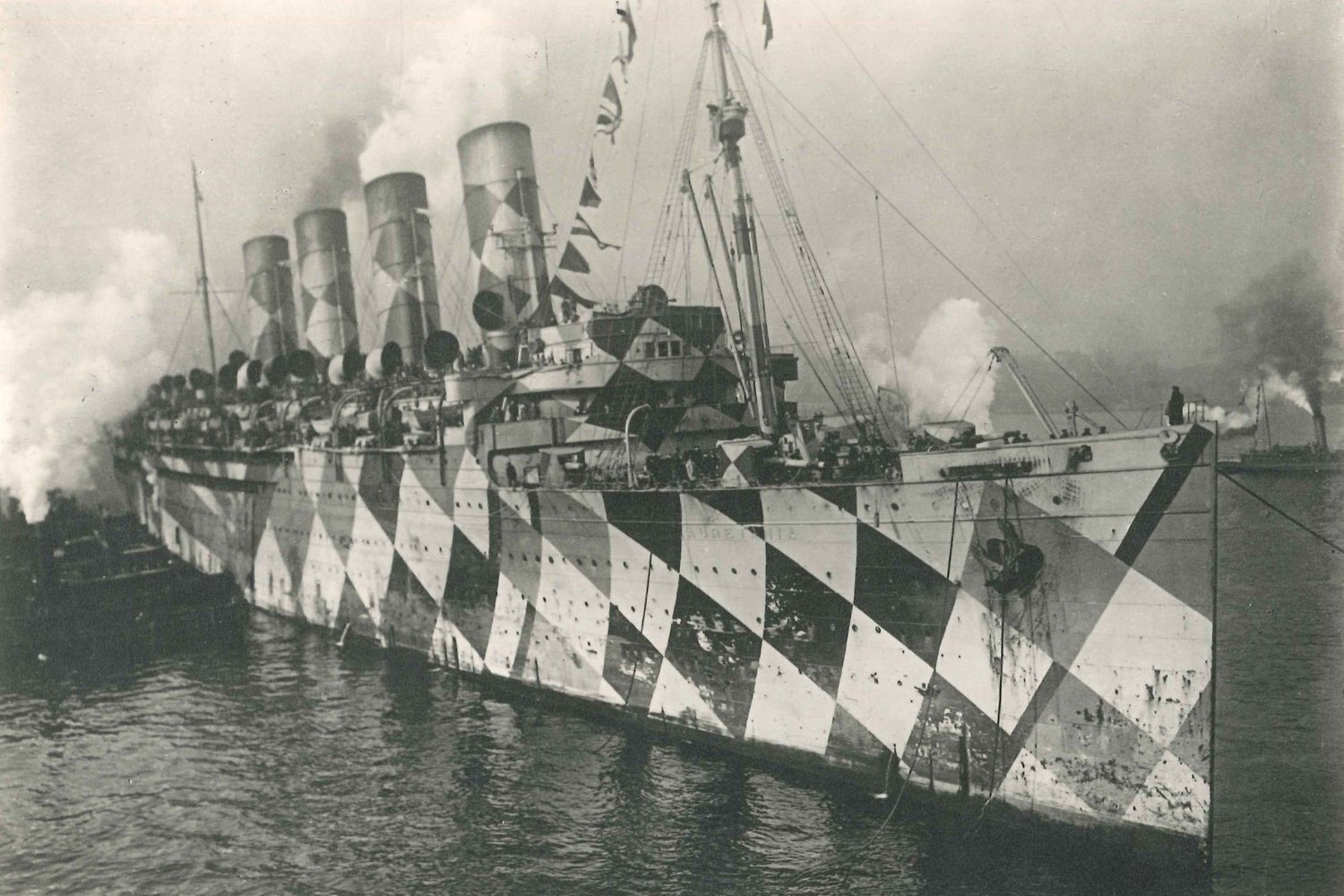

Dazzle camouflage, also known as “razzle dazzle,” was a striking form of warship camouflage used during World War I. Unlike traditional camouflage, which aims to blend objects into their environment, dazzle camouflage employed bold geometric patterns. The intention wasn’t concealment, but rather to confuse enemy U-boat captains about a ship’s speed and heading, making targeting more difficult. But was this innovative camouflage truly effective, or just a visually striking oddity?

Researchers at Aston University revisited a century-old study to investigate the effectiveness of dazzle camouflage on WWI battleships. Their findings, published in Sage Journals, suggest that the “horizon effect”—a visual illusion where a ship appears to be traveling along the horizon even when it isn’t—played a more significant role in misleading observers than the dazzle paint itself. This oversight in the original 1919 analysis reveals a surprising twist in the story of dazzle camouflage.

Re-examining a Century-Old Study

In 1919, MIT student Leo Blodgett conducted a study on dazzle camouflage for his thesis. Blodgett painted dazzle patterns onto a model battleship and observed how these patterns affected an observer’s perception of the ship’s direction when viewed through a periscope. His conclusion? Dazzle camouflage worked.

Arthur Lismer Olympic With Returned Soldiers

Arthur Lismer Olympic With Returned Soldiers

Over a century later, Aston University researchers Timothy Meese and Samantha Strong re-evaluated Blodgett’s methodology. They suspected that the observed perceptual distortions weren’t solely attributable to the dazzle patterns. Strong, a senior lecturer in optometry, highlighted a critical flaw in the original study: the lack of a robust control condition. To address this, the researchers replicated the experiment using photographs from Blodgett’s thesis, comparing the original dazzle patterns with versions where the camouflage was digitally removed.

The Horizon Effect: A Hidden Deceiver

The horizon effect causes observers to perceive a ship as moving along the horizon, even when it’s traveling at an angle of up to 25 degrees relative to it. In fact, viewers tend to underestimate this angle, even beyond 25 degrees.

If dazzle camouflage alone was responsible for the visual deception in Blodgett’s study, observers should have consistently perceived the ship’s bow as turning away from its actual direction of travel. However, Meese and Strong found that in certain situations, particularly when the model ship was moving away from the observer, the bow appeared to turn towards them. This discrepancy suggests that another factor, beyond the dazzle camouflage, contributed to the illusion.

Dazzle camouflage on a ship

Dazzle camouflage on a ship

This additional factor, they concluded, was the horizon effect. Their analysis suggests it played a more substantial role in deceiving observers than the dazzle camouflage itself.

Deceiving the Deceivers

Meese and Strong had already identified the twist and horizon effects in a previous study. However, the surprising finding in their re-analysis of Blodgett’s work was that these same effects were evident in participants familiar with camouflage techniques, including a naval lieutenant. This strengthens their earlier conclusions, demonstrating that even individuals trained to interpret visual deception were susceptible to the horizon effect.

The horizon effect, unrelated to dazzle camouflage, went unrecognized in 1919, effectively “deceiving the deceivers.” While dazzle camouflage may have contributed to some degree of visual confusion, the unintentional illusion of the horizon effect appears to have been the primary source of deception. This new research provides a fascinating reinterpretation of a historical camouflage technique, highlighting the power of perceptual illusions in warfare.