Archaeologists excavating a cave in Segovia, Spain, have unearthed a peculiar, hand-sized rock that naturally resembles an elongated face. Adding to its intrigue is a distinct spot of red ochre pigment, precisely at the tip of what could be interpreted as its nose. This discovery has ignited discussions about early human symbolism and the possibility of Neanderthal art. The researchers behind the find propose this artifact, potentially marked 43,000 years ago, might even hold the world’s oldest complete human fingerprint, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the cognitive abilities of our ancient relatives. However, the hypothesis is not without its skeptics, highlighting the complexities of interpreting our distant past. (108 words)

The Discovery: A Stone Face and an Ochre Touch

The moment of discovery was striking. “We were all thinking the same thing and looking at each other because of its shape: we were all thinking, ‘This looks like a face,’” David Álvarez Alonso, an archaeologist at Complutense University in Madrid and part of the excavation team, told The Guardian. This initial impression led Álvarez Alonso and his colleagues to dedicate three years to meticulously studying the enigmatic stone.

Their research culminated in a compelling hypothesis: approximately 43,000 years ago, a Neanderthal may have intentionally dipped a finger in ochre and pressed it onto the stone’s central ridge. This act, they suggest, not only imbued the rock with symbolic meaning but also left behind what could be the oldest complete human fingerprint ever found. While this finding is captivating and carries significant implications for understanding Neanderthal behavior, some experts urge caution, requesting more substantial evidence to fully support these claims.

Unveiling Potential Symbolic Behavior: The Researchers’ Case

The research team detailed their findings in a paper published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences on May 24, 2024. In their publication, the archaeologists argue that the “strategic position” of the ochre dot strongly suggests evidence of Neanderthals’ “symbolic behavior.” They propose that this object could be a piece of prehistoric art, potentially representing “one of the earliest human face symbolizations in prehistory.”

“The fact that the [rock] was selected because of its appearance and then marked with ochre shows that there was a human mind capable of symbolizing, imagining, idealizing and projecting his or her thoughts on an object,” the researchers elaborated in their paper. This interpretation feeds into a larger, ongoing discussion about the artistic capabilities of Neanderthals. Co-author María de Andrés-Herrero, a professor of prehistory at Complutense University, explained to the BBC that while the capacity of Neanderthals for art is debated, a growing body of evidence over the last decade suggests artistic expression may have emerged earlier in human evolution than previously understood.

Scientific Scrutiny: From Pareidolia to Fingerprints

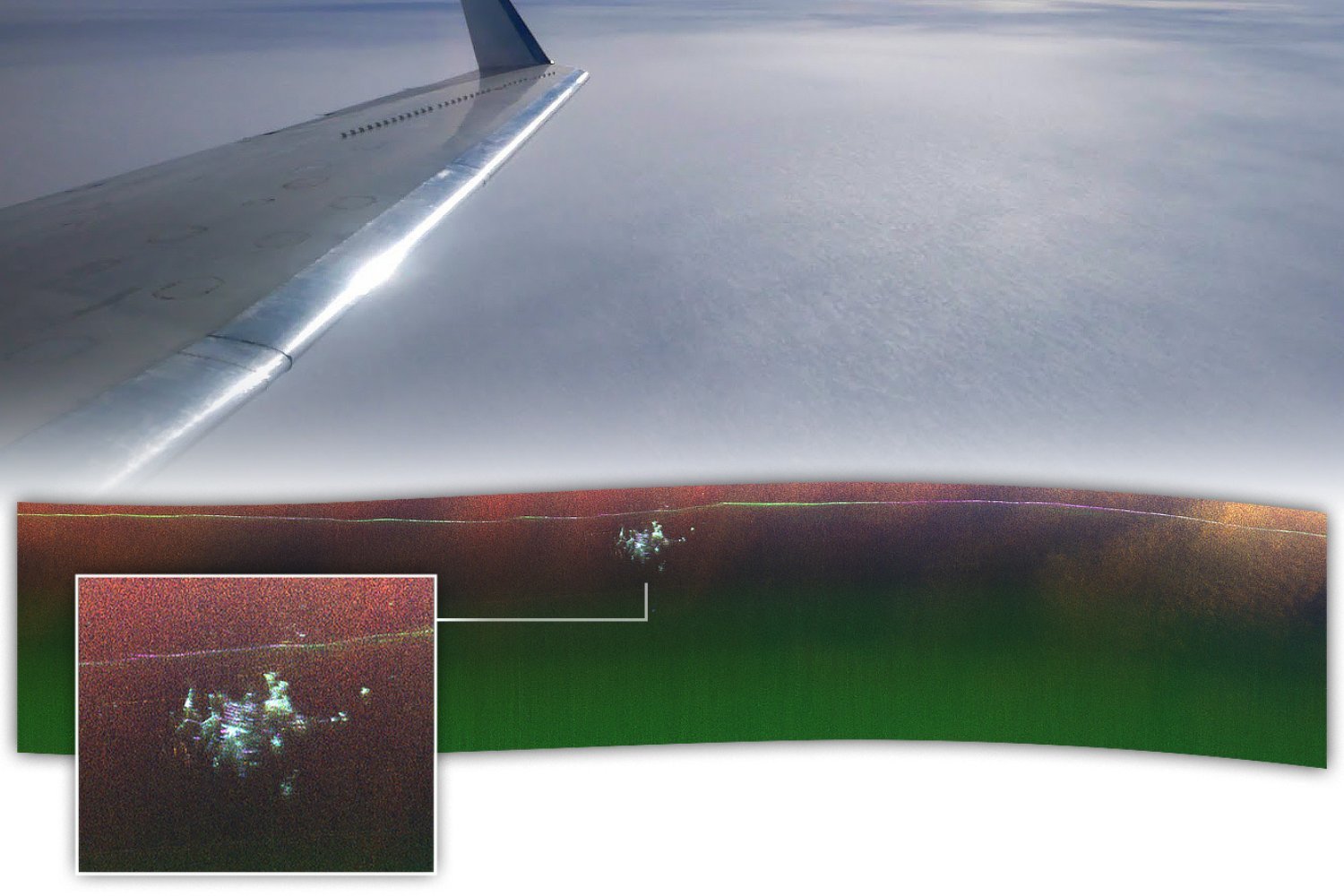

The authors of the new study believe their stone artifact contributes significantly to this mounting evidence. To substantiate their claim that an ancient artist experienced pareidolia—the phenomenon of perceiving faces in inanimate objects—they employed modern technology. A 3D model of the stone’s surface was generated, allowing for precise measurements of the distances between its natural features. Their analysis indicated that the red dot, interpreted as a nose, was positioned in a way that accurately mimics the placement of a nose on a human face.

Further investigation involved geologists, who characterized the red dot and confirmed it was made from ochre, a natural clay earth pigment. Following this, forensic police experts utilized multispectral analysis, a technique capable of revealing details invisible to the naked eye. This advanced imaging confirmed that the red dot was likely applied with a fingertip. Remarkably, their analysis also uncovered ridge patterns within the ochre consistent with a fingerprint, potentially belonging to an adult male Neanderthal. “Once we had that and all the other pieces, context and information, we advanced the theory that this could be a pareidolia, which then led to a human intervention in the form of the red dot,” Álvarez Alonso stated to The Guardian. “Without that red dot, you can’t make any claims about the object.”

A Skeptical Perspective: Questioning the Interpretation

Despite the detailed analysis, not all experts are convinced by the researchers’ conclusions. Gilliane Monnier, a professor of anthropology at the University of Minnesota who specializes in Neanderthal behavior and was not involved in the study, expressed reservations. “The fact that there are these natural depressions—and that we can measure the distance between them and argue that it’s a face—that’s all well and good,” Monnier told maagx.com. “But that doesn’t give us any indication that the Neanderthals who [occupied this cave] saw a face in that [rock].”

Monnier also voiced skepticism regarding the assertion that the red dot was definitively made with a human fingertip. She suggested the possibility that both the coloration and the fingerprint-like ridges could have formed through natural geological or geomicrobial processes. “I would be interested in seeing an explanation by a geologist—someone trained in geology—saying the likelihood of this forming by natural, geological or geomicrobial processes is a very low likelihood,” Monnier added, emphasizing the need to rule out non-human agencies.

The Ongoing Quest for Understanding Neanderthal Cognition

The researchers themselves acknowledge the inherent challenges in definitively proving their hypothesis. They state in their paper that “it is unlikely that all doubts surrounding this hypothesis can be fully dispelled,” and clarify that the pareidolia-driven artistic interpretation should be viewed as a plausible explanation based on the current evidence, rather than an absolute claim. This discovery from the Segovia cave adds another layer to our evolving understanding of Neanderthal intelligence and their capacity for symbolic thought, a key aspect of human evolution.

The face-like rock, with its enigmatic ochre marking, serves as a compelling piece in the complex puzzle of early human creativity and cognition. Whether this find ultimately clarifies or further complicates our understanding of when and how the human mind developed the ability to create and appreciate art remains an open question. Further interdisciplinary research and future discoveries will be crucial in piecing together the full picture of our ancient ancestors’ inner lives and their place in the story of human artistic expression. (788 words total)