The Lapedo Child, a skeleton with both human and Neanderthal features, has finally been accurately dated using a cutting-edge radiocarbon technique. This breakthrough offers a more precise timeline of the child’s life and provides valuable insights into early human history. Discovered in 1998 in a rock shelter in the Lapedo Valley, Portugal, the ochre-stained skeleton was found amongst animal bones, charcoal, and marine shell beads. While remarkably intact, the remains were in poor condition, making accurate dating a challenge until now.

The Lapedo Child belonged to the Gravettian culture, prevalent in Europe between 32,000 and 24,000 years ago, known for their distinctive Venus figurines. Although this culture spanned millennia, recent genetic analysis reveals that Gravettian groups across Europe weren’t closely related. Accurately dating the Lapedo Child offers crucial information about when this specific population inhabited the Portuguese coast. Moreover, the successful dating method can be applied to other Gravettian and Cro-Magnon populations, providing a more comprehensive understanding of early modern human occupation and migration patterns across Europe.

“Previous dating attempts were unreliable due to the limited amount of extractable collagen and persistent contamination,” explained Bethan Linscott, lead author of the study and researcher at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. “The original dates were simply not reliable.”

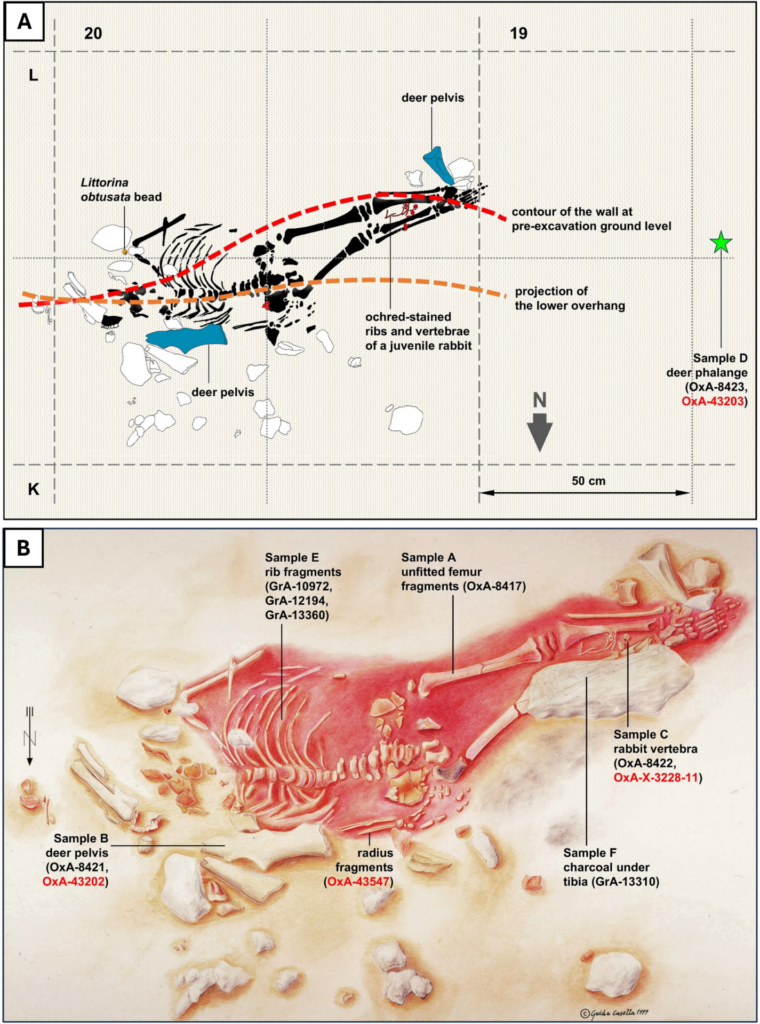

A graphic showing the layout of the child’s burial. Illustration: (A) J.Z. and (B) G. Casella.

A graphic showing the layout of the child’s burial. Illustration: (A) J.Z. and (B) G. Casella.

After four unsuccessful attempts, the research team finally achieved a reliable radiocarbon date using a novel technique called compound-specific radiocarbon dating. This method targets specific amino acids within the bone collagen, minimizing the impact of contaminants. “Instead of dating the entire collagen sample, we focused on hydroxyproline, a unique amino acid acting as a collagen ‘fingerprint’,” Linscott added. “Dating hydroxyproline ensures that the carbon being analyzed originates directly from the bone, eliminating contamination concerns.”

Remarkably, the child’s remains survived a near-disaster. Years before the discovery, the landowner terraced the site to construct a shed, destroying nearly 10 feet (3 meters) of archaeological material. Fortuitously, the child’s burial remained undisturbed.

Analysis of the child’s right radius bone revealed a new age estimate: the child lived between 27,780 and 28,850 years ago, surviving for approximately four or five years. “This refined date confirms initial burial age estimations but alters our understanding of the burial rituals,” Linscott stated.

Previously believed to be ritually burned for the child’s grave, the charcoal beneath the skeleton predates the burial. Similarly, the red deer pelves found in the grave, initially interpreted as meat offerings, are also older than the child. However, Linscott suggests the pelves may have served a practical purpose, perhaps as support during the burial. The presence of rabbit vertebrae, dating to the same period as the burial, suggests a ritualistic placement, possibly a symbolic offering.

The hydroxyproline dating method holds immense potential for refining our understanding of human presence across Europe and beyond. This technique has been used to re-date Neanderthal remains in Croatia’s Vindija Cave, confirming their age to be older than 40,000 years, consistent with the established timeline of Neanderthal extinction. This groundbreaking approach promises to enhance our knowledge of early modern human and Neanderthal movements and occupations, and may even be applied to ancient human relatives worldwide.