The integration of technology into everyday life has been transformative, particularly for people with disabilities. Smartphones, in particular, have become indispensable tools, offering a range of accessibility features. This article explores two innovative apps developed at the University of California, Santa Cruz, that leverage smartphone sensors to provide indoor navigation assistance for the blind.

My first encounter with the challenges faced by visually impaired individuals was during my college years. Interacting with blind students highlighted their reliance on smartphones and the stark lack of assistive technology within the university environment, despite its national standing. This experience underscored the need for innovative solutions to address the accessibility gap. Architect Saif Khan confirms the absence of standardized guidelines for making buildings accessible to the blind, emphasizing the reliance on basic accommodations like ramps. Dr. Arif Waqar, experienced in working with the blind, points to a focus on curative measures rather than practical technological solutions for everyday challenges like navigation.

Indoor GPS: Navigating with Sound

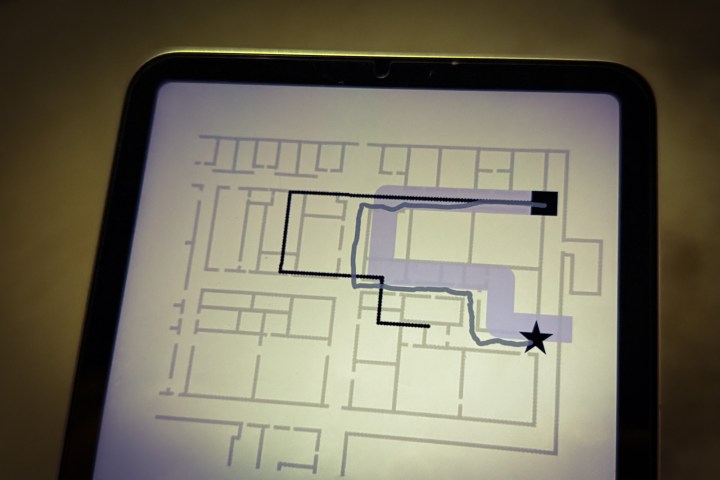

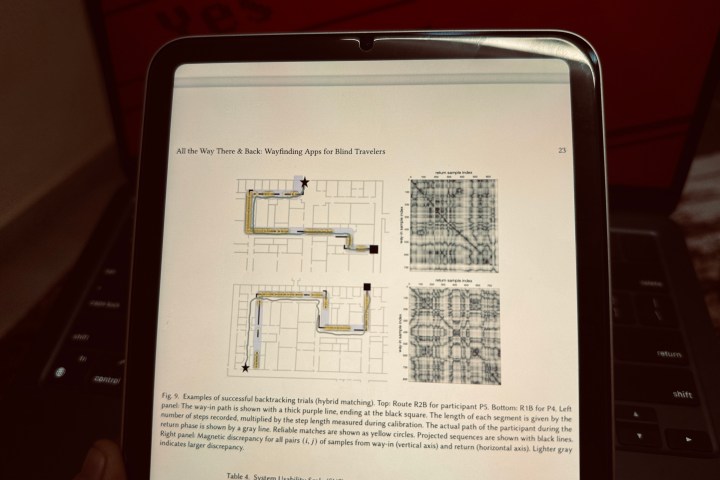

The Wayfinding and Backtracking apps, developed by a team led by Professor Roberto Manduchi at UC Santa Cruz, offer a promising solution. These apps function as an indoor GPS, utilizing a phone’s internal sensors—accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer—to provide audio cues for navigation. Importantly, users don’t need to hold their phones, enhancing safety and convenience. The apps provide directional instructions through the phone’s speakers or a paired smartwatch, guiding users through turns and corridors. Wayfinding aids initial navigation, while Backtracking retraces the user’s steps for the return journey. Future integration of computer vision technology is planned, allowing users to capture images of their surroundings and receive AI-generated descriptions, similar to the functionality of modern AI chatbots.

How the Apps Work: Sensor Fusion and Algorithms

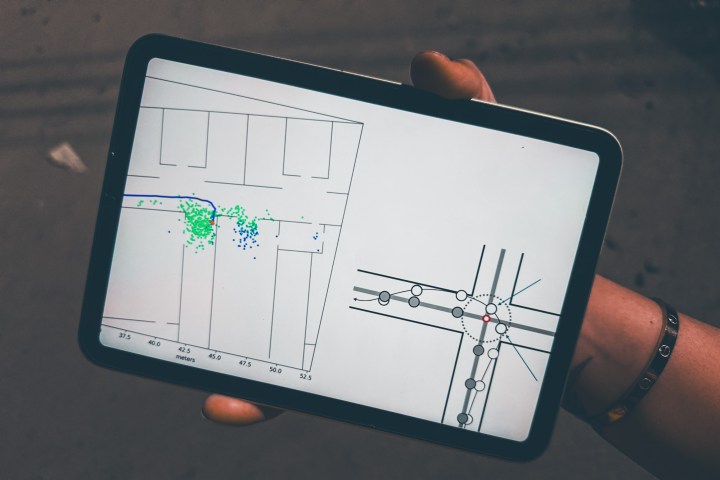

Tested with seven blind participants, the apps proved effective in navigating routes with multiple turns. The apps operate independently of external infrastructure and don’t require specific phone positioning. This is a significant advantage, as users often have one hand occupied with a cane or guide dog. The Wayfinding app employs two algorithms: Azimuth/Steps and RoNIN. Azimuth/Steps uses step tracking and compass data to create a two-dimensional step vector, employing a “dead reckoning” system similar to traditional maritime navigation. To mitigate algorithmic errors or “drift,” particle filtering is used, incorporating constraints based on building floor plans.

RoNIN serves as a backup algorithm. Route calculation relies on Apple’s GameplayKit, a framework typically used for game development. The apps also integrate with Apple Watch for control and feedback. Alerts are provided for upcoming turns, incorrect movements, landmarks, and new route segments.

The Challenge of Floor Plan Accessibility

A key requirement for Wayfinding is the availability of vectorized floor plans. While the team has developed a web app to facilitate floor plan vectorization, the accessibility of these plans remains a significant hurdle. Building owners often provide floor plans in PDF format, while the apps require vectorized versions typically created using software like Revit or AutoCAD. Sharing these detailed maps is often perceived as sharing intellectual property, creating a barrier to widespread adoption. Accessing floor plans for government buildings presents further challenges, requiring permits and approvals.

Open Source: A Path Forward

Open-sourcing the apps is being considered as a solution to address these challenges. This approach could encourage community contributions and facilitate wider access to navigation assistance for the blind. While the apps are still experimental, they represent a significant step toward creating more accessible environments. These innovative applications offer a practical solution to navigate the accessibility gap, bridging the divide between technology and real-world challenges for the visually impaired. They demonstrate the potential of smartphones to empower individuals and enhance their independence. The ultimate success of these apps will depend on collaborative efforts to overcome the hurdles of floor plan accessibility.